Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Sharon M. Harris

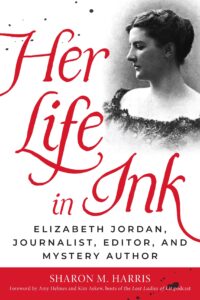

Sharon M. Harris worked in business for several years before she went back to college, finished her B.A., and went on to earn an M.A. and Ph.D., after which she had a wonderful twenty-five-year career in academia. She “retired” in order to have more time to write, and now is a writer full time, focusing on biographies. Her biography of Elizabeth Jordon, Her Life in Ink, was recently released.

Take it away, Sharon!

Writing about an historical figure like Elizabeth Jordan requires living with her over a period of years. What was it like to have her as a constant companion?

Of all the women whose lives I’ve written about in biographies or whose works I’ve recovered from unwarranted obscurity, Elizabeth Jordan has been the most delightful companion of all. When I start working on a biography, I create a timeline, with the person’s birth date at the top and her death date at the bottom. My job is to fill in that timeline with every ounce of information I can find—facts about her life, but also her impressions and those of people who knew her; what she professed in public and what she revealed in private documents; and especially, how she crafted her life. Initially, the search is rather distanced—the outline of a life, a date here and there, a book published, a friend who commented on her. This is the period in which I decide if there is enough substantive information for a biography and, most importantly, if there is something unique about this person that warrants recovering their life. I’m going to spend anywhere from five to eight years with that person, so there must be a powerful life story to tell that deserves such a commitment. I have spent several months on at least half a dozen subjects, only to decide that perhaps their writings are fascinating but there just isn’t anything particularly unique about their lives; or, as happens fairly often when working with eighteenth and nineteenth century figures, if they express racist attitudes. I definitely do not want to live with that for years. But then, as I delve further into a subject, their personality is revealed in multiple layers. That’s when the research becomes fascinating.

Early on in my research relating to Jordan, I realized one word defined her better than other: optimism. She loved life, was fascinated by people, and she had confidence in herself. I found it impossible not to like her and to feel optimistic myself when I was engaged with her. What I also admired was that she knew what she wanted out of life from a young age. She wasn’t a dreamer; she was a do-er. She laid out Plans (insisting on the capital P) for her career and was willing to work her way up in a profession rather than expect opportunities to be handed to her. To me, she was and is inspiring.

You are one of the second wave feminist historians who helped create women’s history as an academic discipline. What sparked that interest for you? And did you face institutional challenges in addition to all the other challenges that confront someone writing about women in the past?

First, let me emphasize that I am, by training and passion, a literary historian. My interest in a subject almost always begins with something they have written that makes we want to know more about them. I did not start my graduate studies expecting to make my career in relation to women writers. In my Master’s I studied Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Faulkner, and in my doctorate, I began the same way. But one of my first Ph.D. courses was in Early American Literature, and I found myself fascinated with the period, broadly conceived. But as the course progressed, I began to think about the fact that there was only one woman on our reading list, the poet Anne Bradstreet. That seemed odd to me and, always driven by the love of research, I started in my “spare time” digging into colonial and Revolutionary histories. Some marvelous women historians were beginning to add to our knowledge in the field, but I specifically wanted to find women writers. And I did! My book, Early American Women Writers to 1800, which collected numerous early writers and offered brief biographies, was published shortly after I graduated.

Early in my graduate studies, thanks to some wonderful women professors, I also became interested in nineteenth-century American women writers. I took every course I could in the field. Then one summer, I went into the university bookstore looking for some light summer reading before I hunkered down to my academic work. I found a copy of a book Tillie Olsen had just published with Feminist Press: Life in the Iron Mills and Other Stories by Rebecca Harding Davis. I couldn’t put it down. I had studied a lot about American Realism as a literary movement, but Davis’s story, published in 1861, was far earlier than any realist work I had studied in classes. That understanding of the genre would change, of course, and Davis’s work was part of that change. Once again, I set off into research, and the more I found, the more I knew I wanted to focus my dissertation on her.

My enthusiasm was not met well by the faculty members I had been working with for several years. Davis wasn’t a “major writer.” I made my case over and over again, until I wore down everyone, and I wrote the dissertation I wanted. “Was her work ‘good enough’ to warrant a dissertation?” was what I had to answer—both for the dissertation and for readers. This question haunted me throughout my career in recovering early and nineteenth-century women’s writings and lives. For years, at every conference where I presented my research, the first question I would receive was “But is her writing any good?” It was after a couple of years of this that I finally responded to the poor soul (always a man, I must admit) who asked it. “I don’t take that question anymore,” I stated. “I would not devote my life’s work to writers who weren’t ‘good.’”

What I did not face was rejection from publishers. I was so fortunate to be delving into these writers just when publishers were recognizing we were tapping into a huge area for new and exciting scholarship. I’m pleased to say that my book on Davis, a revision of my dissertation, Rebecca Harding Davis and American Realism, was published by the University of Pennsylvania and became a standard in the field for decades.

You have written that “recovering” women’s texts—and by implication women’s lives—is only the first step in a multi-phase process. Could you discuss this a little?

Gladly. When I’m writing an article about an author or a biography of her life, I do not believe that I am presenting “the last word” on that subject. Of course, a biography requires placing your subject in historical contexts, and I write as thoroughly as possible about aspects of her life, but once that book is published, it goes out into a wider world. It is offered as a text that other readers and writers will then engage within their own fields of interest and, hopefully, add to our knowledge. Let me take Jordan as an example. I have detailed the many fields in which she was influential—journalism, authorship, magazine editing, book publishing, the film industry, and mystery writing. Scholars within each of those fields can hereafter integrate Jordan more fully into our understanding of those fields. She no longer becomes the single subject, but one who adds to what we know about the many participants in that field and reshape what we thought we knew about a particular era. A journalism scholar, for instance, will be able to add a great deal of depth to our understanding of Jordan’s role in the field and the ways in which she follows certain patterns or created new paths within the profession. A biography offers a rocket launch for greater understanding.

A question from Sharon: I find one of the challenging aspects of a biography to be that all-important Prologue. Your Prologue for The Dragon from Chicago is, to my mind, a model of that aspect of writing. It is beautifully written, gives away enough of Sigrid Schultz’s life to demonstrate why she is an important historical figure, and entices us to read more. How do you decide what to include in the Prologue? how much to give away of the life story while keeping the most important points for the book itself?

With the caveat that I don’t usually think about writing craft in abstract terms:

I think the key is choosing the right anecdote from your subject’s life: one that reveals a key element of their story and requires you to add some historical background . In the case of The Dragon from Chicago I knew almost from the beginning that I wanted to use the story that explained the title. That story has a clear beginning, middle and end, and gave me a space to talk about the treatment of foreign correspondents in Nazi Germany and the main arc of Sigrid’s story.

Also, I try to keep the prologue short compared to chapters in the main body of the book. I aim for roughly half the length of a standard chapter. Word count restraints are a great way to keep yourself focused on what needs to be included.

On the other hand, what do I know?

***

Interested in learning more about Sharon and her work?

Visit her website

Follow her on Instagram

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions with historian Carla Kaplan

Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and a Couple of Answers with Lorissa Rinehart

Lorissa Rinehart is a women’s historian, author, and social entrepreneur whose work explores the intersections of women’s history, politics, war, and peace.

She is the author of Winning the Earthquake: How Jeannette Rankin Defied All Odds to Become America’s First Congresswoman, praised by Publishers Weekly as “an illuminating biography,” and First to the Front: The Untold Story of Dickey Chapelle, Trailblazing Female War Correspondent, which received national acclaim.

Through her newsletter and podcast, The Female Body Politic, she connects 250 years of women’s political engagement to today’s headlines. She is also the co-founder of the Santa Barbara Literary Festival, launching in May 2026.

Take it away, Lorissa!

When did you first become interested in women's history? What sparked that interest?

My initial interest in women’s history was part therapy, part activism, and part spiritualism. I was going through a particularly difficult period in my life with a career I wasn’t passionate about, a truly toxic job, and a bad relationship in a string of bad relationships.

I was adrift without much direction, in large part because I didn’t have any past role models whose legacies I could look to for guidance, wisdom, strength, and inspiration. There was also - and to a certain extent still is - this sense that women weren’t really the heroes of their own stories, but the “also rans” or appendages of their male counterparts. Cause for idle interest but not veneration. Without a past on which I could build a future, I was stuck in this constant present that was pretty bleak.

This wasn’t out of ignorance or a lack of engagement with history. I had always been a history buff. I was that kid in high school who spent lunch in the library reading about the Russian Revolution or Ancient Rome. It was just that women rarely appeared in those narratives, and if they did, they were whores, virgins, or witches for the most part and wives at best. I eventually came to believe that history wasn’t for me - and in many ways it wasn’t.

But, I started spiraling in my personal life - drinking too much, burning bridges, just being generally self-destructive, and I began going back to things I had once loved to hopefully find an anchor that I could cling to. One of those things was history. Except this time, I came to it with a very different lens.

While I was a middling professional at best, many of my female friends were absolute superstars in their fields, from finance to the arts to medicine. Yet, regardless of what they had achieved, they were constantly being passed over for promotion, having their ideas literally stolen, or being told that they didn’t deserve their success. This was, of course, absurd to me - I knew they were awesome. How could anyone not? So, I, and often they, believed it was a fluke, situational rather than systemic.

But when I dove back into history, I found that the very narratives that were being applied to my brilliant friends were applied to so many women in the past, and I began reading with a very different set of eyes.

If a woman was described as pushy, I read her as assertive. If she was promiscuous, I took it to mean she was in control of her own body. If she were a footnote, I figured she threatened the men around her. And if she was difficult - I knew she was powerful.

I discovered history is full of incredible women who have been ignored, undervalued, and silenced for too long, but whose voices have grown all the more powerful and whose lives have become all the more relevant to our own moment. Once I understood this, my own life started to change. Seeing this fierce courage in those who came before, I began to take more risks. I was willing to fail and also be proud of my success. I felt empowered to pursue a dream I had harbored since I was a kid - to be a writer.

I began pitching stories about amazing yet overlooked women to the smallest journals and the biggest magazines. And they started replying with lots of nos, but some yeses too. Then, I got an agent, and soon after, I landed my first book deal for First To The Front, the biography of Dickey Chapelle, a trailblazing female combat photojournalist. Suddenly, the life I had always dreamed of living was no longer a dream, but a reality. I was a full-time writer.

Not because I wrote about women, but because the women I wrote about inspired me to live my passion and showed me that it could be done. And the rest is history, as they say.

What path led you to Jeannette Rankin, and why do you think it’s important to tell her story today?

The path that led me to Jeannette Rankin is almost too uncannily coincidental to be believed, particularly given the incredible relevance of her story in our current moment in history.

After my first book about Cold War photojournalist Dickey Chapelle, I wanted to write a book on the history of small revolutions and rebellions during the Cold War that were far more pivotal in securing a free world than history often remembers.

But my publisher said they’d prefer another biography of a strong and relatively unknown American woman and asked me to send them 5 one-page pitches for women I might like to write about. Jeannette was one of them, and I figured they’d come back and ask for 2 or 3 ideas to be more fleshed out with a chapter synopsis, etc., etc.

Instead, they came back with a contract for Winning The Earthquake.

At the time I started writing, I actually did not know that much about Jeannette or her legacy. But as soon as I started diving in, it became clear that hers was one of the most important stories to be told, right now, with all we are facing in America and around the world.

At the time, Jeannette was campaigning for women’s suffrage in Congress; her home state of Montana was known as a “One Company State” because the Anaconda Copper Mining Company controlled almost every aspect of life. It owned all of Montana’s mining interests and, by proxy, controlled the economy. They bought all but one major newspaper in the state, thereby controlling the news. They even consolidated Montana’s entire power grid. AND, they bribed every elected official to the degree that at the opening of every State Legislative Session, Anaconda paid for a bar and brothel crawl for every elected official down the length of Helena’s main street, Last Chance Gulch, just to make sure they started off the year in a mood to bend the knee to their wishes and an understanding of who actually pulled the strings.

But wait, there’s more.

Jeannette’s first act in office was to vote on whether or not America should join the Great War. Even then, she understood very clearly that war is almost always at the behest of the rich and powerful and at the expense of the people. She also understood that if America joined this war, it would sweep away all of the Progressive reforms so many had worked towards for generations and usher in an era dominated by the military-industrial complex. Talk about prescient.

Her second act was to introduce the bill that would become the 19th Amendment, which somehow we find ourselves defending today. She went on to introduce the first bill appropriating federal funds for women’s health. She also took down the five-term Director of the Printing and Engraving Bureau, Joseph Ralph, who was, along with his all-male managing staff, physically, emotionally, and sexually abusing the bureau's female employees.

AND.

Right after Jeannette was elected, Anaconda Copper went to the Montana State Legislature, which it bought and paid for, and demanded that she be gerrymandered out of her district. She then spent the next 20 years lobbying for global disarmament, famously declaring that“if you prepare for peace, you get peace. If you prepare for war, you get war.”

The parallels continue. But suffice to say, we are living through her legacy.

How does Rankin fit into the larger framework of feminism and social activism in the United States in the early twentieth century?

I don’t often get mad. But what I learned while writing this book really ticked me off.

Basically, while Jeannette was extraordinary, she was not unique. The early 20th Century is absolutely replete with women who not only changed the lives of those around them, but also altered the course of history and shaped our understanding of American life and democracy.

Take for instance Florence Kelley who was a co-founder and first general secretary (old-timey talk for CEO) of the National Consumers League. While Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle famously alerted the public to the abhorrent conditions in meatpacking plants, it was Kelley and those she worked with who actually lobbied Congress, drafted bills, and ultimately shepherded reforms through. They were also diligent in documenting these conditions so there could be no question as to the veracity of workers’ claims of abuse.

Then there’s Ida B. Wells, who was literally born into slavery and, once freed, dedicated herself to the pursuit of truth through the lens of journalism. She was among the first to document the systemic lynching of Black people throughout the South while absolutely burning down the absolute lie that the victims of lynchings were criminals.

Finally, I would point to Mary G. Harris Jones, aka Mother Jones, a refugee of the Great Famine who came to this country as a child and saw the exact models of exploitation she had witnessed as a colonial subject of England being applied to the industrial workers of the United States. Divide, conquer, oppress. She responded by becoming one of America’s preeminent labor organizers who brought the utter cruelty of child labor to national attention, stood up to the private armies of coal barons, led numerous strikes, and inspired thousands of workers to demand their right to organize.

Just to recap: Jeannette Rankin fundamentally reshaped who could participate in government both through the ballot box and in elected office. Florence Kelley literally created, out of thin air, the very notion of consumer safety, and then made it a reality. Ida B. Wells trail-blazed the field of investigative journalism. And Mother Jones gave birth to the modern labor movement.

In no uncertain terms, these are the four pillars of contemporary American life and democracy - all built by women. And yet these very women are ignored, erased, and omitted almost entirely from history. And this really ticked me off.

Not only because they deserve their due, but also because when we see these four pillars under assault, which threatens to crash the very roof of civil society down on our heads, it is clear that this attack is not new. It’s just a more brutal onslaught at the end of a long campaign of quiet eroding.

So, as to the question of how she fits into the larger framework of early 20th-century feminist activism, Jeannette is an integral part of a complex ecosystem that created what we currently understand to be American society, but the complexity and reverberations of which are only now beginning to be understood.

A couple of questions from Lorissa:

I love seeing all your posts, projects, and updates on social media. You seem to be perennially busy. But it begs the question: How do you juggle being an entrepreneur and a historian and an author?

The short answer is, I am not only perennially busy, but perennially overwhelmed.

If you’re looking for the nuts and bolts:

- I rely on a paper calendar that lets me see the whole month at once and a bullet journal that lets me make a plan one day at a time. I separate out the life admin stuff and the writing/speaking stuff into two separate to-do lists.

- I defend my mornings, which are my best work time. If I can get in three or four hours at the beginning of the day I am a happy writer.

- I don’t keep the global to-do lists on the daily calendar. Instead I’ve adapted a 3 and 3 approach for my daily to-do list from Oliver Burkeman. I identify the top three things I need to work on during the day, and then a second set of three smaller things I need to work on. I inevitably don’t get to all six things. Often I end up doing something else all together in response to something urgent that comes up. But at least I’m not staring at all the things that remain undone, which would make me crazy.

- Spreadsheets keep from losing my mind on large projects with lots of details to track, like this series

- Other things that help me keep my butt in the chair, and also help me get out of the chair on regular basis: a timer/stopwatch, two on-line co-writing groups, and a Facebook-based accountability group of writers, scholars, and one very creative artist. (You people are the best. *waves*)

And I still occasionally drop the ball.

What advice would you give to aspiring historians who are looking a particularly bleak job market?

I am probably the worst person in the world to answer this question.

Forty years ago (45 years ago if you want to be picky), the first thing my graduate school advisor said to me was “You do know there are no jobs, right?” Without the promise of a teaching job at the end of the road, I organized my life accordingly. I got a “real” job that was interesting enough to keep me interested while I took the long road to finishing my dissertation. And I poked at anything that caught my imagination. Finally I drifted into writing. That is not a replicable model.

Is there any advice to be had in there? Figure out what you really want to do as a historian. (It may not be what you assume it is.) If you really think you want to be a professor, talk to some people who are working academics about what their work life looks like. Explore all the opportunities.

***

Want to know more about Lorissa and her work?

Visit her website

Subscribe to her weekly newsletter and podcast, The Female Body Politic,

Follow her on Bluesky

Follow her on Linked-In

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with literary historian Sharon M Harris

Dr. Florence Sabin: A Career with a Second-Act Twist.

Dr. Florence Sabin (1871-1953) was one of the first women doctors to build a career as a research scientist.

Sabin was interested in math and science from the beginning. She attended Smith College, where she majored in zoology. One of her professors encouraged her to study medicine at Johns Hopkins new co-educational medical school.[1]

Sabin worked for three years as a high school teacher before she had enough money to pay the tuition for her first year of medical school. She entered the program in 1896, one of fourteen women in a class of forty-five.[2] While still a student, she made a model of a baby’s brain stem that would be used in medical textbooks for years to come. She graduated with honors in 1900 and then served three internships .

She went on to have a spectacular career of “firsts.” In 1902 she became an assistant professor of embryology and histology[3] at Johns Hopkins, the first faculty position to be held by a woman. She was promoted to associate professor in 1905 and to full professor in 1917—again the first woman to hold either position. She was the first woman president of the American Association of anatomists in 1924 and the first woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1925. That same year, she left Johns Hopkins to join the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research as head of the Department of Cellular Studies. She was—you guessed it—the first woman to be a full member of the Rockefeller Institute.

Sabin was dubbed “the [ahem] First Lady of American Science.” During her years at Johns Hopkins, she did pioneering work on the development of the lymphatic system, overturning accepted knowledge, and perfected the technique of supravital staining, which allows scientists to observe the structures of living cell tissue. At the Rockefeller Institute, she led research on the pathology of tuberculosis. She made major contributions to medical knowledge at both institutions. It was a solid career by any standard.

* * *

In 1938, at the age of 67, Dr. Sabin retired and moved back to Denver, where she had spent part of her childhood. She planned to spend her time reading, studying, and taking road trips in the mountains with her sister, who had also recently retired, after forty years teaching math in the Denver public schools. ( I must say sounds pretty wonderful.) Instead she found herself on a crusade to improve public health conditions in Colorado.

Sabin did not go looking for the cause, it came to her.

Out of 20 major causes of death in the United States, Colorado exceeded the national average in 13, including diphtheria, bubonic plague, typhoid and tuberculosis. . Many of those deaths were the result of inadequate laws controlling waste disposal and milk inspection.

Politicians in Colorado knew that conditions were bad in the state, but they had no interest in changing public health laws, which had last been updated in 1897 . Local health officials were patronage positions, generally appointed as a reward for political loyalty without regard for medical qualifications. Even if local officials raised concerns about conditions lobbyists for the mining, meat packing, and dairy industries, all of which had considerable power, ensured that expensive new laws were not enacted.

When the governor asked Sabin to head a committee to inspect health conditions in the state in 1944, he did not expect the retired scientist to do more than hold a few meetings, file a report, and go away. Apparently he hadn’t bothered to look learn anything about Dr. Sabin before he appointed her.

Sabin began by collecting data. She visited every county in the state, inspecting dairy floors and the public drinking water supply. Appalled at what she found, she drafted a group of health bills that required milk be pasteurized, sewage be treated, and patronage appointees in the local health offices be replaced with trained medical professionals.

The lobbies fought back. Legislators buried her bills in committees and walked out when she spoke at the capitol.

When the legislature failed her, Sabin drove across the state stirring up support for health reforms. Her motto was simple, “Health to match our mountains.” She spoke at town hall meetings and grange halls.[4] (When a group of local politicians told her they didn’t have the budget to treat sewage, she pulled a jar of local, unfiltered water out of her bag and set it on the table in front of them.) More importantly, she met with women’s clubs, church groups and parent-teacher associations, telling women about the health risks to their children. She talked about sewage, contaminated milk and high rates of preventable deaths.Thousands of letters from angry mothers poured into the capitol. Harder to ignore, politicians who actively opposed the Sabin Health Bills were voted out of office in 1946.[5] The Sabine Health Bills passed in 1947. Colorado became a model of public health.

Sabin retired for a second time in 1951, at the age of eighty. (None of my sources say how she spent her time but I doubt if she sat on the porch doing nothing.) In October 1953, she died of a heart attack just before her 82nd birthday.

[1] A medical school had been part of the original plan for Johns Hopkins, but a major loss in the university’s endowment meant the medical school was put on hold. A group of prominent Baltimore women who believed in higher education for women, led by philanthropist Mary Elizabeth Garrett, raised money to help finance the school, with two radical conditions. The first was that women were accepted as students. The second was that the school be a full-fledged graduate program, with the requirement that all applicants had to have bachelor’s degrees with a core of science classes and a reading knowledge of French German, the major scientific languages of the day. The academic requirement was an even more extreme change than the admission of women. (There may be a rabbit hole with Garret’s name on it in my future.)

[2] Opening the doors is only the first step. Something many of us found out in the 1970s and 1980s.

[3] I assume I’m not the only person in the Margins who doesn’t know what histology is. I looked it up, so you don’t have to: Histology is the study of the microanatomy of cells, tissues and organs. In other words, the stuff you can only see with a microscope. You’re welcome

[4] For those of you who don’t know, The National Grange of the Order of Patrons of Husbandry, commonly known as The Grange, was founded in 1867 to help rural America recover from the devastation of the Civil War. “Grangers” fought against discriminatory railroad pricing, established local buying cooperative, and advocated for rural mail delivery. Local grange halls were often the social heart of rural communities, and the perfect place for Sabin to make her pitch.

[5] A useful reminder that political change is often driven by activism at the local level.

* * *

Come back on Monday for three questions and a couple of answers with historian Lorissa Rinehart.