The Whiskey Rebellion

“No taxation without representation” was a rallying cry in the American Revolution*, but taxation controversies didn’t go away after the United States was formed. The new government needed regular revenue. The average man on the street (or dirt road through the wilderness) was opposed to taxation and had his doubts about government in general. Some questioned the value of a revolution if all it did was replace British aristocrats with local elites.

In 1791, at the urging of Secretary of State Alexander Hamilton, Congress levied the new government’s first nationwide tax: an excise tax ** on distilled spirits produced in the United States. Large commercial distillers in the east grumbled, then raised their prices to pass on the cost of the “whiskey tax” to their customers. Small farmers in the west, many of whom distilled and sold whiskey because it was difficult to transport their grain over the mountains, did more than grumble.

The government had trouble collecting the tax almost immediately. Many western distillers simply didn’t pay. Others met the brand new “revenooers” with violence–not only beating tax officials but anyone who rented them housing or an office. In July, 1794, five years after the former colonies had adopted a new constition, opposition flamed into open rebellion when US Marshall David Lenox arrived in western Pennsylvania to serve writs against distillers who had failed to pay the tax. The so-called Whiskey Rebellion spread rapidly. By the end of the month, several thousand armed rebels had gathered in Braddock’s Field near Pittsburgh. The same leaders who cheered on the Boston Tea Party less than years before now had to contend with a tax protest of their own.

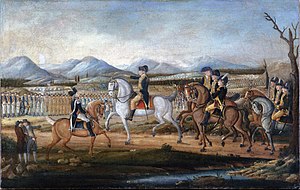

On August 7, President Washington alerted the state militias to stand by and sent in negotiators, but the whiskey rebels had no interest in negotiated. In September, Washington himself led 13,000 militiamen from Carlisle, Pennsylvania over the Alleghenies to the town of Bedford.*** In Bedford, Washington turned the command over to General Henry “Lighthorse” Lee, then governor of Virginia. By the time the federal forces arrived at Braddock’s Field, the rebellion had collapsed and most of the rebels had retreated to their farms.

The federal government had proven it could maintain order, but opposition to taxes and federal authority wasn’t at an end. Farmers in Pennsylvania rose in protest again in Fries’s Rebellion in 1799. A few veterans of the Whiskey Rebellion decided that it was more effective to fight from the inside and went into politics. Thanks to their efforts, the hated whiskey tax was repealed and replaced with duties on imported goods, something that would become an issue in the lead up to the War of 1812.

* I didn’t really need to tell you that, right?

** I realized I didn’t really know what an excise tax was. I looked it up, so you don’t have to. It’s a tax on a good produced inside the country.

***The only US president to personally lead armed forces while in office.

I really like reading news about Whiskey rebellion. Thanks for that informative post! Best wishes, Chris Eric.