From the Archives: Building Baghdad

I currently have my head down trying to finish a big project that I’m excited about. Instead of driving myself crazy trying to write blog posts at the same time or, worse, “going dark” I’ll be running some of my favorite posts from the past for the next little while. Enjoy. And I’ll see you soon.

Today we think of Baghdad in terms of tyranny, terrorism and mistakes. A sinkhole for American troops. A sandbox for suicide bombers.

In the eighth century, Baghdad was the largest city in the world–and the most exciting. Like Paris in the 1890s, Baghdad was a cultural magnet that drew scientists, poets, scholars and artists from all over the civilized world. (Just for the record, that didn’t include Europe, which was having a bit of trouble on the civilization front in the centuries after the fall of Rome.)

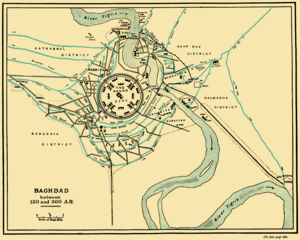

Baghdad was a brand new city, built to replace Damascus as the capital of an Islamic empire that was no longer the sole property of the Arab tribes. The Abbasid caliph al-Mansur had his architects draw the outer walls of his new capital in a perfect circle, using the geometric precepts of Euclid.

Completed in 765, the Round City grew quickly. Within fifty years, it had a population of more than a million people: Muslim and Christian Arabs, non-Arab Muslims, Jews, Zoroastrians, Sabians and an occasional Hindu scholar visiting from India. It had separate districts for different trades, including a street devoted to booksellers and papermakers.

Most important of all, Baghdad had libraries. Encouraged by an official policy of intellectual curiosity, scholars in Baghdad collected works of literature, philosophy and science from all corners of the empire. (Baghdad reportedly negotiated for a copy of Ptolemy’s Megale Syntax as part of a peace treaty with Byzantium.) Ambitious nobles followed the caliphs’ example and created their own libraries, many of which were open to scholars. Working in a culture that encouraged learning, Abbasid scholars in the eighth through the tenth centuries not only transcribed and translated the classical scholarship of Greece, Persia and India, they transformed it, pushing the boundaries of knowledge forward in mathematics, geography, astronomy and medicine.