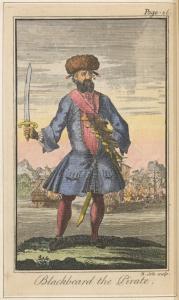

From the Archives: When Is A Pirate Not A Pirate?

I currently have my head down trying to finish a big project that I’m excited about. Instead of driving myself crazy trying to write blog posts at the same time or, worse, “going dark” I’ll be running some of my favorite posts from the past for the next little while. Enjoy. And I’ll see you soon.

When is a pirate not a pirate? When he’s got a license to steal.

From the 16th through the mid-19th centuries, governments issued licenses, called letters of marque, to private ship owners that gave them permission to attack foreign shipping in times of war. Called privateers, these government-sanctioned pirates were an inexpensive way for governments to patrol the seas. Private investors outfitted warships in the hope of earning a profit from plunder taken from enemy merchants.

Unlike pirates, privateers had rules they had to follow. They were only allowed to attack enemy ships during times of war. Sometimes their commissions limited them to a specific area or to attacking the ships of a specific country. In exchange for following the rules, they would be treated as prisoners of war if they were captured.

In fact, it was sometimes hard to tell a privateer from a pirate. If a privateer attacked foreign shipping in peace time, interfered with the ships of neutral countries, or was just too violent, he was sometimes treated as a pirate if he was captured. Some privateers, like Sir Francis Drake, became national heroes. Others, like Captain William Kidd, were hanged as pirates.

Privateering was made illegal in 1856 by international treaty.

Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.