Cornelia Fort: Eyewitness to Pearl Harbor

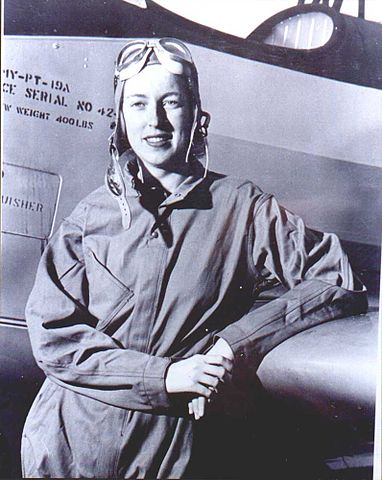

Cornelia Fort was a certified civilian flight instructor who worked for the Andrews Flying Service in Honolulu, a Nashville debutante who had kicked her way into the male dominated world of general aviation. (1) She was only 22 and already an experienced pilot with hundreds of flight hours to her credit.

On December 7, 1941, Fort was in the air with a student pilot, a defense worker named Suomala who was practicing landings prior to taking his first solo flight. As was typical at the time, they had no radio, so the only way to avoid other aircraft coming and going at Honolulu’s John Rodgers Airport was to scan the sky around them

Prior to what was scheduled to be Suomala’s final landing before soloing, Fort scanned the sky. She saw a military plane heading in from the ocean. She was so accustomed to military traffic from the nearby military bases that she nodded to Suomala to turn into the first leg of his landing pattern. She looked again and saw another military aircraft headed right for them. She grabbed the controls away from her student, jammed the throttle open, and pulled above the oncoming plane. It passed under them, so close that their celluloid windows rattled.(2)

Fort glanced down to see what kind of plane it was. Instead of the insignia of the US Army Air Corps, painted red balls shone on the wings in the morning sun: the “rising sun” emblem of the Japanese. With a chill tingling down her spine, she looked west to Pearl Harbor, where she saw billowing black smoke and formations of silver bombers. Something detached itself from one of the planes and she watched as the bomb fell and exploded in the middle of the harbor.

She landed the plane at John Rodgers as quickly as she could, surrounded by machine gun fire. As they touched down, Suomola asked “When am I going to solo?” (Fort later said she wasn’t sure whether he didn’t understand what was happening or was trying to lighten the situation with humor.) A contemporary newspaper account reported her answer as “Not today, brother.” A few seconds later, the shadow of a plane passed overhead and bullets spattered around them. Pilot and student sprinted for the cover of the hanger.

Once inside, Fort tried to warn others that the Japanese were attacking. She was met with disbelief and laughter. The men she worked with tried to pass it off as some sort of maneuvers that she had misunderstood. Fort was “damn good and mad.”(3) She was about to tell them off when a mechanic from another hanger ran in and told them that strafing planes had just shot another pilot and his student as they ran for cover.

As scores of Zeros roared by, some no more than fifty feet off the ground, Fort and her companions took shelter in the hangar. When she examined her plane the next day, she found it riddled with bullets.

Newspapers soon picked up the story of Fort’s encounter with the Japanese–it would have been a good story no matter who was involved. But a pretty young female aviator gave it an additional human interest element. For a time, she was part of the speaking tour that sold war bonds. But she was determined to use her flying skills for the war effort. Lamenting the fact that she she couldn’t be a fighter pilot and face the Japanese in the air again, she was the second woman to volunteer for the Women’s Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS).

For several months she delivered small training planes(4) up and down the east coast. In February, 1943, Fort and several other WAFS was assigned to Long Beach California to deliver the much larger BT-13s. They were thrilled with the “promotion” to larger planes, but some of them remained frustrated by the fact that they were not allowed to become fighter pilots. Determined to acquire some of the skills needed, Fort and a few of her companions began to experiment with formation flying, an activity that was forbidden during delivery flights. On March 21, 1943, while participating in a forbidden stint of formation flying on a delivery, Fort’s plane was destroyed in a mid-air collision, making her the first WAFS pilot to die while on duty.

What a waste.

(1) Her father made her brothers promise never to fly. He never thought to ask for the promise from his daughter. Her brothers were royally pissed off when they found out she had been taking flying lessons in secret.

(2) Fort’s written account of the incident claims that at this point she felt “a distinct feeling of annoyance that the Army plane had disrupted our traffic pattern and violated our safety zone.” My guess is that she swore like a fighter pilot–or at least gave vent to a string of the “dangs” and “sssssss–sugars” that passed for profanity among women of the Middle South at the time.

(3) And can you blame her?

(4) PT-19s, for the aviation fans among the Marginalia