Telling Women’s History: Three Questions and An Answer with Theresa Kaminski

Theresa Kaminski and I are co-administrators (and occasionally, co-conspirators) for a Facebook reading called Non-Fiction Fans, where readers and writers of narrative nonfiction meet up to talk about great non-fiction and how it gets written. She is also a wonderful writer of women’s history and a generous member of the on-line literary and historical community.

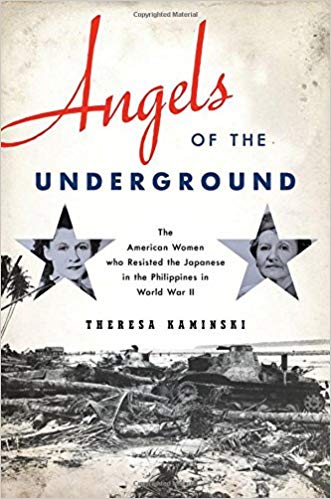

Theresa describes herself as a recovering academic. She taught American history and American women’s history for over twenty years. She has written a trilogy of books about American women in the Philippine Islands during the 20th century, the most recent of which is Angels of the Underground: The American Women who Resisted the Japanese in the Philippines in World War II. Theresa lives in southwestern Wisconsin, in a small town known as the troll capital of the world.

And now, let’s turn it over to Theresa:

How would you describe what you write?

I’m always aiming for narrative history. It sounds straightforward enough, but because of my academic background, I have a hard time separating story from information. I have to keep reminding myself I don’t have to include three examples for every point I’m trying to make. I’m a big admirer of Jill Lepore who always tells a terrific story that is well-grounded in historical facts.

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

Absences of source materials and/or silences within them. Because history has–well, historically focused on politics and war, documentation by and about women has been considered less important. Most of it wasn’t saved, at least not in official archives. When women’s experiences began to be restored to the historical record (the field of women’s history really began to take off in the 1970s), valuable sources were found in places like the attics and basements of private homes. That diary great-grandmother kept while she worked at a munitions factory during World War II, those letters great-great grandmother wrote home to her family after she moved to Greenwich Village to work for a socialist magazine–those kinds of things. It’s interesting to note the kinds of things that women left out of these documents, too, which typically involved matters of sexuality. So researching women is kind of like trying to put together a huge jigsaw puzzle.

You are currently writing biographies of two very different women in different historical periods. Is it a challenge to keep their stories separate in your head? And are you finding similarities between them?

The differences between Dr. Mary Walker and Dale Evans make it easy to keep them separate.

Walker was a woman of the 19th century. Everything about her life–every experience, every idea–was somehow tied to women’s rights. She became a medical doctor because that’s what she wanted to do with her life. She didn’t think that being a woman should restrict her from doing so. She wanted to treat wounded soldiers during the Civil War because she thought it was her duty as a doctor and a citizen. She didn’t think that being a woman should prevent her from doing so. She always wanted to be somebody. Walker’s relentlessness is simply fascinating–talk about a woman who persisted!

Evans was a woman of the 20th century. But one thing she had in common with Walker was the determination to be somebody. In Evans’s case, of course, that meant celebrity. Most people remember her as the smiling cowgirl wife of the singing cowboy Roy Rogers. Most people know little of how she got to that point in her life–that she started off as a popular radio singer with a dream of being a Broadway star. Instead, she became a B-movie actress before moving on to television. She had a pretty dramatic private life. And she had a very complex relationship with feminism and the second-wave women’s rights movement.

Question for Pamela: Was there a woman that it almost killed you to leave out of Women Warriors because she had a great story but didn’t quite fit the scope of the book?

There were several. Harriet Tubman, for instance. But the one that hurt the most was Queen Tamar (1156-1184), of Georgia, a trans-Caucasian kingdom on the eastern edge of the Medieval Christian world. Her father named her his co-ruler and heir apparent when she was only nineteen and required Georgia’s patriarchs, bishops, nobles, viziers and generals to swear allegiance to her. After his death, Tamar successfully defended her throne against an attempted power grab by her husband and a group of disaffected nobles and went on to lead her country in expansionist wars during a period that is considered the golden age of Georgian history.

I intended her to be in the book in tandem with the Empress Maud of England, whose father also named her his co-ruler and heir and who also had to defend her throne after her father’s death. I had to cut them both once I had a working definition of a military commander as someone who is near the front lines, plans operations, makes command decisions, and gives orders. The sources available to me made it clear that Tamar traveled with her troops and appeared on the battlefield, but were fuzzy on the other elements of command. I. Was. Not. Happy.

I’m still want to write about Maud and Tamar if I can figure out the right format.

Want to know more about Theresa Kaminski and her work?

She blogs about women’s history and the writing life at https://theresakaminski.com/.

Her Twitter handle is @KaminskiTheresa

(Drop in tomorrow for the next Telling Women’s History interview: I’ve got an entire month of some of my favorite history people talking about the work they do and how they do it. Next up: Scott Stern, author of The Trials of Nina McCall.)