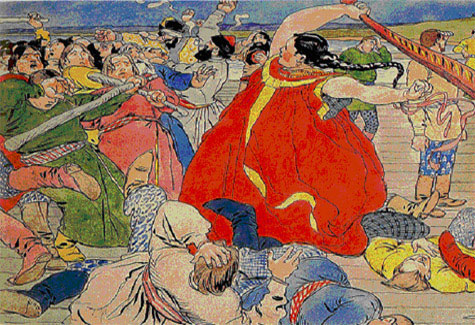

And speaking of Slavic women warriors

In my last blog post, I mentioned the medieval tradition of Slavic women warriors known as polianitsy: horse-riding, sword wielding female warriors from the steppes. I was frustrated that I didn’t know more. After all, women warriors from across the globe have dominated my intellectual life for the last few years. So I went digging.

The first thing I realized was that I had gone on this particular snipe hunt before. In the early days of working on what would become Women Warriors, I looked at a lot of literary and folk traditions of women warriors. Some, like Viking shield maidens, had an accompanying tradition of scholars arguing for their existence. Others did not—or at least did not have a scholarly tradition that left a trace in languages I can read. The polianitsy were in the second camp and I not only moved on but apparently forgot most of what I knew about them.

In fact, the polianitsy are a recurring feature in Russian folk poems and medieval romances. The term is often translated as knights. Disguised as men, these female knights ride into battle and often fight against the bogatyri , who are the larger-than-life knight-errant heroes of Russian epics.(1) A recurring element in these epics is the moment when a polianitsa is unmasked, usually at sword point, and is transformed from worthy opponent to worthy sexual partner. (2) In one variation on the theme, the unmasked female knight turns out to be the bogatry‘s daughter, born after a previous encounter with an unmasked polianitsa.

In the course of poking around in the subject, I found several scholars who have drawn a long, shaky line between the polianitsy and real life women warriors who fought for Russia in the First and Second World Wars. It’s a bit of a leap. But maybe the polianitsy created a space for women warriors in the Russian imagination. There’s a reason, “see it, be it” is a powerful concept.

(1)It should be pointed out that some scholars have attempted to connect individual bogatyri to historical figures. Perhaps it’s just a matter of time until someone suggests a real-life counterpart for one of the polianitsy. Or for that matter, perhaps someone already has and I didn’t find it. If you have a reference for this type of discussion, let me know.

(2) Shakespeare wasn’t the only author to take advantage of the gender bending possibilities of a girl disguised as a boy.

Curious what you mean by a ‘shaky line’? Do you mean the tradition of women serving sereptitiously, or a literal line like a family tree? Or something else?

I meant an attempt to draw a historical connection between the epic characters in the past and the historic existence of later real-life women warriors. The suggestion that the first made a mental place for the second. That seems like a leap to me.