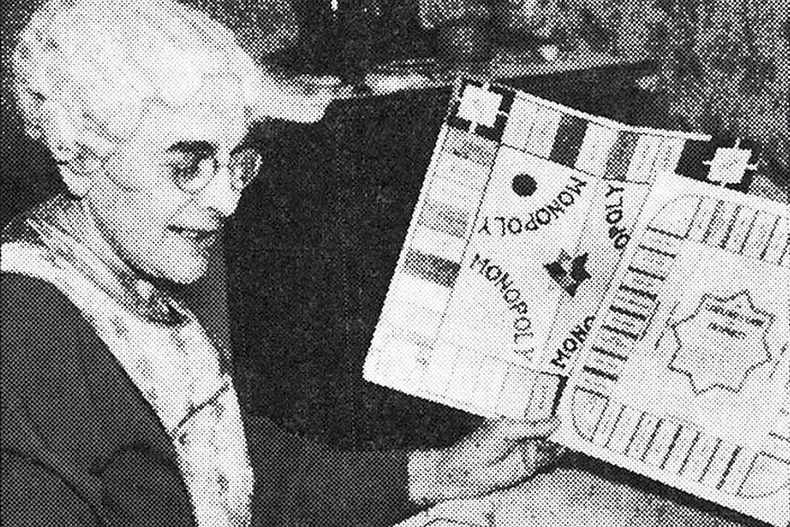

The Lady Who Invented Monopoly

Recently a long-time blog reader, named Jack French, reached out to me with a story for a blog post: “Elizabeth “Lizzie” Magie Phillips, the real inventor of Monopoly, not Charles Darrow, the guy history incorrectly credits as inventing this game”. As anyone who has read more than a few posts here on the Margins can guess, this is the kind of story I find irresistible. It more than lived up to my hopes.

Take it away, Jack:

In Atlantic City, NJ today a prominent plaque honors Charles Darrow, termed the inventor of Monopoly, a classic board game in which all the streets are named for those in Atlantic City. The only problem is….Darrow did not invent Monopoly (a woman did) and he didn’t even name the streets (another woman did.) The creation of this game, which has sold over 200 million sets, resulted in a convoluted and fascinating historical narrative.

Elizabeth Magie, born in Illinois in 1866, always called herself Lizzie. She became a writer, an actress, a reformist, and the inventor of seven published games. In 1904 she obtained a patent on a board game she called The Landlord’s Game. It had 40 spaces, 22 properties, 4 railroads, and both JAIL and GO TO JAIL spaces, exactly the same as Monopoly would eventually have. Lizzie designed the game, not for fun, but to demonstrate the avarice of landlords of that era.

In 1910 she married Albert Phillips and later revised her board game while living in Washington, DC, changing some rules and adding draw cards such as: “Caught robbing the public; players will now call you ‘Senator’.” Lizzie patented this version in 1923 but Parker Brothers turned it down as “too political.”

Throughout the U.S., individuals and groups, ignoring her patents, formatted her game into their own versions, usually with local street names. About 1930 Ruth Hoskins, principal of a Quaker school in NJ, reformatted the game by assigning all streets the names of ones in Atlantic City. It was this version of the game that fell into the hands of Charles Darrow, an unemployed engineer in Philadelphia. He was trying to support his small family during the Great Depression by creating and selling puzzles and games. He had previously tried wooden jig saw puzzles and a revised bridge game score pad.

Around 1932 he began making his own version of Lizzie’s game (ignoring her patents) starting with a large circle of oil cloth, rather than the more expensive pressed paper-board. Later he switched back to the square board. Darrow did all the printing himself and then marketed the games in person. He was fairly successful and presented it to both Parker Brothers and Milton Bradley in 1934. Both refused it, stating that the game took too long and was too complicated.

But he persevered, getting department stores in Philadelphia to sell it and those substantial sales finally convinced Parker Brothers to take it on in 1935. In working out the contracts, Lizzie’s patents were finally recognized. Parker Brothers went to her and bought out her 1923 patent (the 1904 one had lapsed.) They paid her a lump sum of only $ 500, but contracted to market three more of her other games. In addition, Parker Brothers agreed to put her name as originator on the cover of all Monopoly games. But that promise quickly deteriorated and by the 1940’s the firm was promoting Darrow as the sole inventor. Over the years, Parker Brothers and Darrow would go on to make millions from Lizzie’s invention.

Lizzie died in 1948 at the age of 82. She is buried in Columbia Gardens Cemetery in Arlington, VA, located about a mile from the National Cemetery. She is resting in good company; among the other notables interred in this cemetery are Roy Buchannan, esteemed guitarist, and Jerome Karle, chemist and Nobel Prize winner.

+++++++++++++++++++

SOURCES:

Timeless Toys; Classic Toys and The Playmakers Who Created Them by Tim Walsh (Andrews McMee Publishing, 2005)

90 Years of Fun by Parker Brothers (Parker Brothers, 1973)

The Billion Dollar Monopoly Swindle by Ralph Anspach (Palo Alto, 1998)