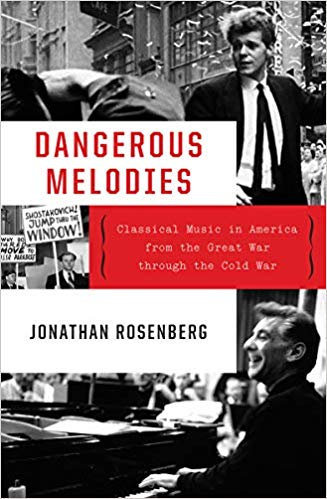

Dangerous Melodies

Several years ago, I reported on an excellent book about how pianist Van Cliburn’s victory at Russia’s first Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958 helped change the course of the Cold War.

It was a revelation, but I didn’t realize that the culture battles of the Cold War were only one example of the role that classical music played in American cultural and political life for much of the 20th century. In Dangerous Melodies: Classical Music in America from the Great War through the Cold War, Julliard-trained musician and historian Jonathan Rosenberg explores the surprising ways in which classical music in the United States became repeatedly tangled in international politics.

It is a complicated and often ugly story. Music lovers divided into two camps. Musical nationalists found it difficult to separate the United States’ troubled relationships with Germany, Italy and later Russia from those countries’ musical heritage. Musical universalists believed that music not only rose above nationalism but could be used to heal schisms between nations. For more than 50 years the two groups clashed repeatedly over questions of who should be allowed to perform in American concert halls and opera houses and what music they should be allowed to play, forcing the directors of musical institutions to make hard decisions. The music of Beethoven, Brahms, Strauss, and Verdi, among others, became the focus of heated debate, and occasional violence. With the advent of the Cold War, the role of music and politics became even more complex as the United States government deployed American musicians as ambassadors for “the image of freedom in oppressed countries abroad.”

In fact, Rosenberg argues, neither the fears of the musical nationalists nor the hopes of the musical universalists proved true. At most, classical music gave Americans a forum for discussing the nature of loyalty, patriotism, democracy, freedom and oppression. Who knew?

Much of this review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.