Talking About Women’s History: More Than Three Answers and a Question with Sarah Rose

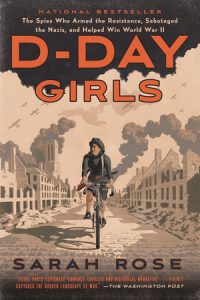

Sarah Rose is a journalist and bestselling author of D-Day Girls: The Spies Who Armed the Resistance, Sabotaged the Nazis and Helped Win World War II, and For All the Tea in China: How England Stole the World’s Favorite Drink and Changed History. A former news columnist at the Wall Street Journal, her feature writing appears in Outside, The New York Post, Travel + Leisure, Bon Appetit, The Saturday Evening Post, and Men’s Journal. Sarah is a graduate of Harvard College and the University of Chicago.

I’m pleased to have her here for what turned out to be seven questions and an answer!

How did you discover the women you write about in D-Day Girls?

I was interested in writing about women in the military – how do women operate in traditionally male spaces? When I asked the question “Who was the first woman in combat?” I discovered it was the women of SOE, the Special Operations Executive. And it wasn’t a new phenomenon, it was 75 years old and we had mostly forgotten their stories.

D-Day Girls tells the story of three fascinating women. Do you have a favorite among them?

I suppose I feel most strongly about Andree Borrel because she wasn’t able to tell us her story. Almost everything we have is a secondhand source. A lot of energy went into figuring out what happened to her, so we know a lot, but in her voice we only have these 5 letters she managed to sneak out of prison before she died.

How does your experience as a journalist inform your work as a historian?

I don’t really think of my work as a reporter and as a historian separately. My trade is sources and stories. When I was reporting, it was always my job to know everything about my subject before an interview, and I spent a lot of time in the morgue, or in databases, researching. As a historian, it’s harder (though not impossible) to interview live sources, but there are still vast swaths of original documents that tell the story. It’s my job – as a reporter or a historian – to interrogate sources and make them cohere as stories.

How would you describe what you write?

I write narrative non-fiction. Traditional history can be bland, written from the point of view of the present, from a results-oriented perspective, as if the conclusion was obvious to everyone at the time. But that’s not how we live at all. No one knew how D-Day would turn out, Eisenhower had no clue. And if you read the histories, it is taken as a given that the Allies won the day. I don’t know who wins the 2020 election. We have no idea how our own lives will end, this is the human condition. So I try to write a story that is true, but I want it to read like lived experience, as if it were a great novel. I am not allowed to make anything up – everything, every thought from a character, every bit of dialogue, every description of every room can be sourced.

Who are some of your favorite authors working today?

Erik Larson is the master of narrative non-fiction. I study everything he writes, I try to reverse-engineer why his books are such a pleasure to read, why they work and how he is just so good.

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

Women’s work is historically mis-categorized. When I started D-Day Girls, the scholars in the field said women of SOE “didn’t do much” or “they were just couriers” as if parachuting behind enemy lines and blowing up Nazi installments, surviving Gestapo interrogation is somehow not much. And what they mean is it’s not as important as the male agent’s work. (This is, according to men…) If you center the women’s stories – make the men the marginal players – whole new narratives reveal themselves.

So for instance, if we were to pick one thing in WWII that changed the war more than anything else, that did more to turn the war in favor of the Allies, we could reasonably argue that it was ULTRA, the decrypting of the Enigma machine, that allowed us to get our convoys across the Atlantic and overpower Hitler. This was work performed overwhelmingly by a female workforce, Bletchley Park was 80 percent women. So, led by a gay man, Alan Turing, a force of primarily women won World War II.

It takes centering the experiences of marginalized voices to even see an argument that women won the war. This isn’t about participation trophies: we are less safe now, as a nation, if we don’t recognize the way women — and women’s work — contributes to the national defense.

Do you think Women’s History Month is important and why?

It helps to see ourselves in history to make history. We need role models. We shouldn’t have to break every glass ceiling for the first time. Some ceilings were already broken but the stories got lost, mostly because men wrote the stories. There are hidden figures everywhere.

May there be so much equality someday that every month is women’s history month.

And a question from Sarah for Pamela: Tell us about a woman (or group of women) from the past who has inspired your writing.

At the personal level, my grandmother who told me stories about her own childhood that inspired my interest in the past and my mother, who is also a writer and who taught me by example about seizing time to write even when it wasn’t easy.

Moving beyond my own circles: I want to be Barbara Tuchman when I grow up. Like Eric Larson, she was a master of narrative non-fiction. And she pursued stories that caught her imagination across a broad range of periods and topics.

Want to know more about Sarah Rose and her work?

Check out her website: https://sarahrose.com/

Follow her on Twitter: https://twitter.com/thesarahrose

* * *

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with historian Kimberly Sherman, who asked me a really tough question.