Wrapping My Head Around the Weimar Republic

When I started looking at the possibility of writing about Sigrid Schultz last April, what I knew about the Weimar Republic could be summed up in Peter Gay’s assertion in his classic Weimar Culture: The Outsider as Insider* that the Weimar spirit is embodied in “Gropius’ buildings, Kandinsky’s abstractions, Grosz’s cartoons, and Marlene Dietrich’s legs.” **

To the extent that we think about the Weimar Republic at all, many of us see it through the lens of the Lost Generation. (Think Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, which morphed into the musical Cabaret.) And in fact, Weimar Berlin was the darker counterpart of interwar Paris. It is the city of Expressionist art, Dada-ism, modernism, The Three Penny Opera, political satire, subversive cabaret, and sexual freedoms. With the (well-earned) reputation of being the most licentious city in Europe, Berlin drew an international community of artists, political dissidents, journalists, and intellectuals, not to mention stray members of the Lost Generation engaged in what a later generation would term “finding themselves. ”

But that is only one side of the story. And maybe not the most important one. It didn’t take me long to learn that the Weimar Republic in general and Weimar Berlin in particular were defined by more than sex, drugs, and cabaret. Born in revolution, it was a period of enormous social and political creativity. It was also a period marked by growing economic crisis, recurring political crises (internal and external), constant political intrigue, occasional political assassinations, attempted coups, labor unrest, and regular street violence between supporters of different political view points.

The Weimar republic only lasted from 1919 through 1933. It is easy to overlook it as pause between the two world wars. But the more I read about it, the more important it seems. I’ll keep you posted.

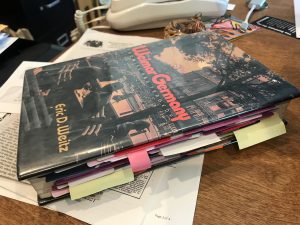

*I’m not going to review this one beyond saying that it is well worth reading if you want to know more about modernism and Weimar and you aren’t bothered by the application of Freudian theory to an entire culture. If you are looking for a broader picture, as I was (and am), I strongly recommend Eric D. Weitz’ Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy, which combines economic, political and social history in complex and thought-provoking ways. As you can see, another book stuffed full of sticky tabs, always a good measure of how useful I find a particular volume to be:

**I suspect that Marlene Dietrich’s songs are going to be the sound track for this book.

I know very little about the Weimar Republic. But the dates really jumped out at me bc they align very closely with the Prohibition Era in the USA (1920-1933). One of the many fascinating aspects of Prohibition to me is the resulting backlash of crime and relaxing/crumbling of the ascetism of social mores. I wonder if Berlin had a similar rebound, or was it just ‘anything goes’?

The Weimar Republic didn’t have Prohibition. In fact, when a pair of American aviators landed in Germany after a transatlantic flight (soon after Lindbergh) the first thing they asked for was a glass of beer, a Pilsener if available! That said, Germany definitely suffered from (or enjoyed) its own version of the Roaring Twenties, with a backlash against traditional mores and art. Plus lots of political violence, ended with the rise of the Nazis.