Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Judy Batalion

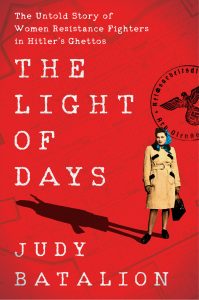

When I heard Judy Batalion’s new book, The Light of Days, described as “Inglourious Basterds”– if the “basterds” were teenage Jewish girls who hid grenades in their underwear to kill Nazis,” my first thought was “I need to read that book. “ My second thought was, I need to talk to the author for Women’s History Month. I’m so glad I did.

Judy Batalion is the author of White Walls: A Memoir About Motherhood, Daughterhood and the Mess in Between. Her essays have appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Forward, Vogue, and many other publications. Judy has a BA in the History of Science from Harvard, and a PhD in the History of Art from the Courtauld Institute, University of London, and has worked as a museum curator and university lecturer. Born in Montreal, where she grew up speaking English, French, Hebrew, and Yiddish, she now lives in New York with her husband and three children.

Take it away, Judy:

We are seeing more and more books about female spies and members of the resistance in World War II, both fiction and non-fiction. Do you think there is a reason that we are drawn to these stories now?

That’s a great question, and I have two answers. First, some backstory: I found the primary Yiddish source material for this book in the spring of 2007, just after I submitted my dissertation in feminist art history. I knew that the stories I’d found – testimonies about Jewish women who tricked the Gestapo into carrying their luggage filled with contraband, hid revolvers in teddy bears, flung Molotov cocktails, and bombed German supply trains – were incredible, and yet, at the time, I also knew that they would not be “commercially viable.” As I’d learned from my Ph.D. work, women’s history just wasn’t in vogue. I was granted translation funds from an academic institution and, for many years, planned to release my research in an academic sphere. It was only after the first Women’s March, after Trump took office in 2017, that I pitched this idea to my literary agent, who immediately saw this story as one well-suited for a trade publication. Around that time, a new type of feminism was developing alongside a popular fascination in lost women’s histories. All to say, one reason is the social zeitgeist.

My second answer has to do with the subjects of these stories (and many of the fictional accounts published now are based on real people). Many of these WW2 female survivors stayed silent about their war tales for most of their lives. Sometimes they weren’t believed; other times, they were blamed for fighting instead of helping their families; frequently they were accused of sleeping their way to safety. Many women suffered terrible survivor’s guilt. Mostly, many women wanted to suppress their memories to raise “normal children” and create a healthy, happy new generation. Despite this, the second generation often felt ashamed of their outsider, refugee parents. It took until my generation, the 3Gs, to feel pride in this legacy, to ask our “grandmothers” about their lives. The WW2 survivors finally started talking, aware that they needed to tell their stories before they died. I think we’re now seeing books published based on these late-in-life conversations and ruminations.

The Light of Days tells the story of a group of fascinating women. Do you have a favorite among them?

You can’t have a favorite child! I was drawn to each woman for a different reason, mostly because they were so unlike me. These women were daring, cunning, passionate, and willing to take risks against-all-odds. Having said all that, when I went to have my headshot photographed for the book, I was having trouble posing. Before The Light of Days, most of my published work was humorous, and my photos always showed me smiling; I had perfected the cheeky glance, looking up at the camera above my glasses frames. For this shoot, however, I had to project something serious. I did not know how. The excellent photographer pushed me to think about my subject material, to focus intensely on one woman whose story I wanted – needed – to tell. I immediately thought of Frumka Plotnicka. Known as “di mama,” (the mother, in Yiddish) for her ability to listen, counsel and comfort, she returned to Nazi-occupied Poland on her own accord. She established soup kitchens and cultural programs to help ghettoized Jews; she slipped in and out of ghettos and traveled across the country bringing Jewish communities information, hope and supplies; she strategized uprisings and negotiated with Poles and Nazis; she was offered papers to leave the country for The Hague but would not go. But alongside her colossal strength and bravado, Frumka also had trouble making friends; she was intense and awkward and broke down a few times during the war – all that I could certainly relate to. Frumka died, age 29, while shooting at Nazis, clutching a revolver. If I didn’t tell her incredible story, who would? I feel close to her, in an ethereal, writerly way.

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

A real research challenge for me in this project was names. I struggled with my characters’ names, a struggle that was amplified because they were women. The women in my story, like most Polish Jews, had Polish, Hebrew, and Yiddish names, as well as nicknames. Some had a wartime alias or several. Sometimes, they used other fake identities for emigration papers; it was usually easier to leave Europe if a woman was faux married. Then many changed their names to suit the languages of the countries where they ended up. (For instance, Vladka Meed began as Feigele Peltel. Vladka was her Polish undercover name; she married a Miedzyrzecka, which was changed to Meed when they moved to New York.) Further, I searched for these Slavic and Hebraic words in English search engines, based on combinations of Latin letters. For example, I found my protagonist Renia Kukielka under Renia, Renya, Rania, Regina, Rivka, Renata, Renee, Irena, and Irene; Kukielka has infinite Anglo spellings, as does its Yiddish “Kukelkohn.” Then Renia had various false wartime document names—Wanda Widuchowska, Gluck, Neuman. Plus, the married name added a layer that often complicates women’s traceability: “Renia Kukielka Herscovitch” (or possibly Herskovitch or Herzcovitz) has endless permutations. The story of Renia Kukielka could easily have slipped through, been lost forever.

My question to Pamela: Since you are so wonderfully steeped in women’s history, I would love to hear what you recommend as a great and surprising women’s history book or even TV show right now?

Women’s history month is a rough time around here (and by around here, I mean in my head). I end up with a whole bunch of books I want to read, added to the pile of books I already wanted to read and no time to do more than dip in here and there. That said, two very different books have grabbed me by the imagination and are keeping me reading:

The Secret History of Home Economics: How Trailblazing Women Harnessed the Power of Home and Changed the Way We Lived by Danielle Dreilinger—I was a hostile reluctant home economics student when I was forced to take the class in eighth grade. (And I still think that the class as I experienced it was caught in a timewarp.) The revelation that home economics was a feminist project in its roots is an eye-opener. (Just so you know, the book won’t be released until May. Sorry)

The Daughters of Kobani: A Story of Rebellion, Courage and Justice by Gayle Tzemach Lemmon.—I loved Lemmon’s earlier books so I was eager to read this one, and she doesn’t disappoint. Beginning with the statement “I told myself that I had given up war,” Lemmon is sucked into the story of an all-female Kurdish militia unit fighting against Isis, and to make women’s equality a reality in the process. She sucked me in, too.

* * *

The Light of Days will be released on April 6, but you can pre-order it now wherever you buy your books.

Want to know more about Judy Batalion and The Light of Days?

Check out her website: https://www.judybatalion.com/

Follow her on Twitter: @JudyBatalion

Follow her on Facebook: Judy Batalion Author

Follow her on Instagram: JudyBatalion

* * *

Come back tomorrow for a whole bunch of questions and an answer with Julia Charles, talking about Jessie Redmon Fauset and the New Negro Renaissance.

* * *

If you’re interested in the process of writing and thinking about history, you might enjoy my newsletter, which comes out roughly every two weeks. The content is totally different from History in the Margins. In recent months I’ve discussed cliffhangers, the odd experience of reading history “in real time” in the form of old newspapers, the question of “first-naming” the subject of a biography, and , well, women photojournalists. (You can tell where my mind’s been lately.) If that sounds like your fistful of daffodils, you can subscribe here: http://eepurl.com/dIft-b .(When you subscribe, you’ll get a link for a very cool downloadable timeline of the Roman emperors and the women who fought against them or supported them, which I created with the people behind The Exploress podcast.)