History on Display: The Buffalo Bill Center of the West, pt. 2 –The Buffalo Bill Museum, Man of the West, Man of the World

[If you’re joining us late to the subject, you can find an overview of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in my last post.

It is not surprising that the Buffalo Bill Center of the West, in Cody, Wyoming, has an entire museum dedicated to Buffalo Bill Cody, and his Wild West Show.* And I wasn’t really surprised, though somewhat saddened, by the fact that the Buffalo Bill Museum was much more crowded than the museum devoted to Plains Indian history and culture. I was surprised by the ways in which the curators used Cody’s story as a lens through which to consider the subject of America’s westward expansion, and to question that popular image of the American west which Cody himself did so much to promote. And I was deeply amused by the number of Buffalo Bill look-alikes among the attendees.

In the first twenty years of his life, Cody took part in some of the most iconic experiences of the United State’s westward expansion.

Cody was born in 1846 in Iowa on the western banks of the Mississippi, which was the dividing line between east and west. The family moved to what became known as “Bleeding Kansas” when the Kansas Territory opened up for settlement in 1854. His father died in 1857 in the violence that surrounded the question of whether Kansas would enter the United States as a free state or a slave state. With his father’s death, eleven-year-old Cody became the family’s principal means of support. He found work on wagon trains carrying supplies west for the freight company, Russell Majors and Waddell. According to some accounts, he paused to try his hand as a prospector in the Pike’s Peak gold rush in 1859. (He seems to have been determined to try all the things.) When Russell Majors and Waddell established its famous and short-lived Pony Express mail service in 1860 and advertised for “skinny, expert riders willing to risk death daily,” fourteen-year-old Cody signed on. (Or maybe not. Cody regularly contributed to his own legend and sometimes it’s hard to untangle fact from fiction. And there was a lot of fiction. According to the museum, Cody is the hero of more fictional accounts than any other figure in American history.) Two years later, as troubles heated up on the Kansas-Missouri border, he joined the “jayhawkers,” anti-slavery vigilantes who raided across the border into Missouri. When the Civil War began, he enlisted in the Union army, working first as a scout and later as a member of the Seventh Kansas Cavalry, which saw action in Missouri and Tennessee. After the war, he headed west again, working as a buffalo hunter for the railroads, which needed meat to feed their construction crews. In 1868, he returned to the army as chief scout, earning the Congressional medal of honor in 1872.**

For those of you who have not been keeping track, Cody was now 26 years old*** and well on his way to becoming an American folk hero, thanks to a series of short stories, novels, and plays about the adventures of Buffalo Bill. At some point after 1872, he made the transition from army scout to American showman. By the early 1880’s millions of people in North America and Europe knew Cody as Buffalo Bill.

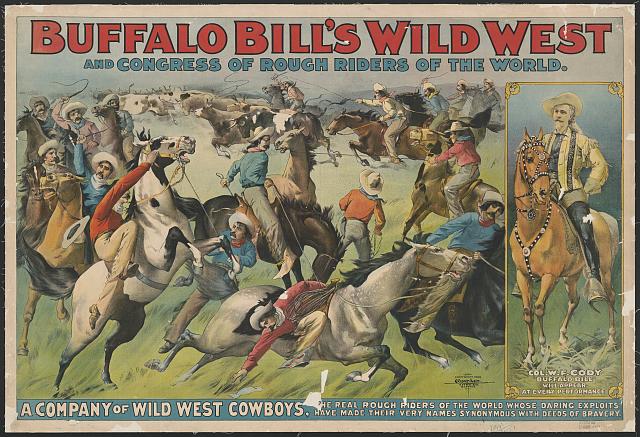

A large part of the exhibit deals with the creation of Cody’s public persona as Buffalo Bill, his role in creating that persona, the development of the Wild West Show and the Congress of Rough Riders of the World, the importance of the Wild West Show in shaping the image of the American West, and the tension between Cody the person and his persona. I was fascinated. So fascinated that I stopped taking notes—not a conscious choice and something that almost never happens. (My favorite fact: Cody was in favor of women’s suffrage.)

I came away from the Buffalo Bill Museum with one big idea: before Buffalo Bill, most people saw cowboys as social outcastes. Through his Wild West Show, Buffalo Bill created the image of the cowboy as a heroic icon and elevated the United State’s westward expansion to an epic adventure.**** That’s powerful stuff.

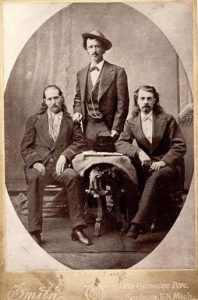

*Not to be confused with Wild Bill Hickok, seen here with Buffalo Bill and Texas Jack Omuhundro at the time of Cody’s first Wild West show, Scouts of the Prairie (1873), in which all three men performed. Their paths crossed a lot and I for one find it easy to muddle the combination of Wild and Bill.

**His medal was revoked in 1917, when Congress retroactively tightened the rules for the honor. One of those changes was that the award could only be given to military personnel, and scouts were considered civilians. (To which I can only say, huh?) His medal was reinstated in 1989.

***Anyone else feel like a slacker by comparison?

****Leaving out big chunks of the history in the process, as happens when history is transformed into myth or reduced to comic book.

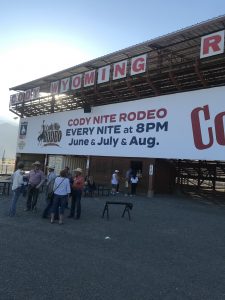

Travelers’ Tip: While you’re in Cody, make sure you visit the nightly rodeo. Lots of fun, though I must admit in the events that involved lassoing and typing up an animal, I found myself rooting for the animals.