From the Archives: Button, Button, Who’s Got the Button?

We drove through Buffalo Iowa early on a Sunday morning, just as Judy’s Barge Inn, a local variation of the more common Dew Drop Inn, was opening for the breakfast crowd. It was too early for a local historical society to be open. It was not too early to stop and read the local historical marker, which reminded us that Buffalo, like other small towns along this stretch of the Mississippi was part of the nineteenth century’s button boom, which we learned about in 2019 during an earlier trip on the Great River Road.

The nineteenth century button industry based on fresh-water mussels was a recurring theme of our ten days on the Great River Road this year.

In 1891 a German button manufacturer named John Frederick Boepple opened a button factory in Muscatine, Iowa, after a change in tariff laws caused his business in Germany to fail. Shell buttons weren’t new. The Boepple family had made buttons from shells and horn for many years. But the plentiful mussel shells found in the Mississippi River near Muscatine were thick and well suited for cutting into buttons.

At the time that Boepple opened his small factory, the McKinley tariff of 1890 meant that imported shell buttons were expensive. The original foot-operated lathes that Boepple adapted from those used to make buttons from ocean shells were designed to allow skilled craftsmen to create a button from beginning to end, which meant that even without the additional cost of the tariff buttons were not cheap.* With the introduction first of steam-powered lathes and then a revolutionary machine called the Double Automatic that, well, automated the process, attractive mother-of-pearl buttons were affordable to the average household. By the late nineteenth century, buttons made from river mussel shells were so popular that bars in at least one river town accepted mussel shells as payment.

Like other industries along the Great River Road, buttons were a boom and bust business. “Clammers” earned good livings harvesting shells from the river in large quantities. Button factories sprang up in towns up and down the Mississippi, creating hundreds of factory jobs and more opportunities for cottage industries where women and children sewed buttons to cards at home. In the same way that the logging industry overcut the great forests of Minnesota and northern Wisconsin, by the 1920s, the button industry had decimated the Mississippi’s mussel population, and precipitated its own demise.**

* Today we tend to think about buttons as nothing in particular. Or more accurately, unless you knit or sew, you probably don’t think about buttons at all unless you have to sew one back on your jacket. (A skill everyone should learn, in my opinion.) But historically buttons were a luxury item: made by hand and often from expensive materials. It turns out there was a good reason my grandmothers (and probably yours) kept a button jar. (For that matter, I still have one.)

For those of you who’d like to know more, I recommend this article:

http://www.slate.com/articles/life/design/2012/06/button_history_a_visual_tour_of_button_design_through_the_ages_.html

** The related story of efforts to restore the river mussel population was also a recurring theme of our trip. At one time there were 51 species of mussels in the upper Mississippi; today theater are 38, eighteen of them endangered.

I still have my grandmother’s button jar. It is a prized possession, though the button are pretty pedestrian. I used to keep my own with all the spare buttons sent with blouses, but eventually realized I have never once used the button jar. Grandma’s button jar is a keepsake, my own button jar was trash.

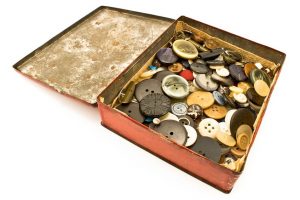

I also have a button collection, in a tin box. Some inherited, some added by me over the years. I husband the buttons, now that the Windsor Button Shop of Boston, which had everything under the sun, has closed.

I grew up in Buffalo in the 1980s, and a random memory led me here. I don’t recall ever seeing the buttons themselves, but the beachfront was LITTERED with shells that had holes punched out of them.