From the Archives: The Last Laugh

We had a wonderful time in Hannibal, Missouri, the childhood home of Mark Twain, aka Samuel Clemens. But I was a little disappointed that the museums didn’t barely touched on his later life, which was fascinating and heartbreaking. For any of you who are curious about Mark Twain after he became Mark Twain, I offer this book review, which originally ran in May, 2016.

###

I realize that my United States citizenship may be revoked for saying this, but I am not a fan of Mark Twain’s work.* I am, however, eternally fascinated by Mark Twain’s career, which was a roiling broth of ambition, depression, and innovation. Consequently, I was much happier to read Richard Zacks’ newest book, Chasing the Last Laugh: Mark Twain’s Raucous and Redemptive Round-the-World Comedy Tour , than to read Twain himself.

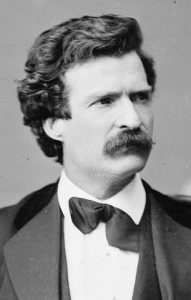

- Mark Twain ca. 1871 Who knew the younger Twain was a hottie?

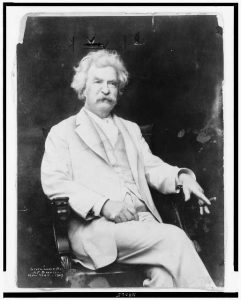

- Mark Twain ca 1907 Looking the way we all picture him

In 1896, Mark Twain was sixty years old, the beloved author of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, and the United State’s highest paid writer. He was also on the verge of financial disaster, most of which he had brought on himself through a combination of cock-eyed optimism and impatience with details. Determined to keep a larger percentage of the proceeds from the sale of his books, he had founded his own publishing company, which proved to be a cash drain rather than a source of income. He poured money into James Paige’s innovative typesetting machine, which was eclipsed by the Merganthaler Linotype in the nineteenth century’s version of the technological duel between Beta and VHS–and encouraged others to do the same. He signed documents he didn’t understand. He filed for bankruptcy, but continued to be pursued by creditors who refused to believe the luxury-loving author had nothing. Finally, Twain saw only one solution: to go back on the public speaking circuit, which he had happily left twenty-five years before.

In Chasing the Last Laugh, Zacks turns the circumstances that led Twain to undertake a year-long tour of the English-speaking world and the tour itself into a combination of high drama, black comedy, and occasional tragedy. The result is a lively and insightful study of the claims of celebrity, the value of controlling the public narrative, and the mercurial figure of Twain himself.

*Those of you who are sharp-eyed may remember that I also recently expressed my lack of enthusiasm for Ernest Hemingway. In case anyone is getting the impression that I am uniformly “agin” male American authors from the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, I would like to point out that I am a big fan of F. Scott Fitzgerald (the short stories) and Dashiell Hammett. (Choosing two off the top of my head. )

I detect a bit of what I said on the last segment you sent and of course you are correct. In this commentary, by your augmenting I learned even more about him and those around him. One thing leads to another as always. Like or dislike it all depends on which book of his I am reading at the time, I guess.