From the Archives: Pippi Longstocking Goes to War

(Okay, I admit it. That’s an inaccurate, click-bait of a title.)

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. I hope you enjoy an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins.

- Astrid Lindgren, 1924

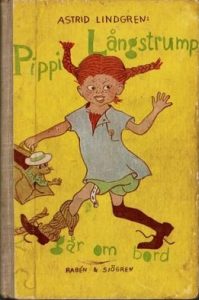

Today Astrid Lindgren is famous as the creator of Pippi Longstocking: the red-headed quirky rebel who proclaimed herself the strongest girl in the world.* In World War II, Lindgren was a 30-something housewife and aspiring author. Her war diaries, published posthumously in Sweden and recently translated into English, are a fascinating account of life in neutral Sweden during World War II.

If you read War Diaries, 1939-1945 hoping to get insight into the creative process behind Pippi Longstocking, which was published just before the end of the war. you will be disappointed. There are few references to her writing. If you want a wartime narrative written by an intelligent observer that offers a different perspective than the British accounts most familiar to American readers, Lindgren’s your girl.

The diaries are a mixture of the personal and political. Marital problems, concerns about her son’s difficulties at school and rumors about increased rationing are intermixed with her determination to document the course of the war. She lists the menus for birthday dinners and holiday celebrations, commenting each time on how lucky Sweden is to have abundant food and fearing that each feast will be the last. She pastes in newspaper clippings of critical events.

She also adds privileged information that adds depth to her reporting. Lindgren worked on the night shift for a government security agency responsible for censoring correspondence sent from or to other countries. Although her work was so hush-hush that her children did not know what she did, she had no hesitation about copying and commenting on sections of the letters in her diaries, including letters describing the transportation of Jews to concentration camps in Poland as early as 1941.

Lindgren’s War Diaries tell the story of the war as seen through the veil of Swedish neutrality—a veil that Lindgren recognized was perilously thin. She records her relief and guilt over Sweden’s relative prosperity, her shame over allowing German troops to travel through Sweden, and her fear that Russia will prove to be a greater threat to Sweden than Germany. For those of you who are serious World War II buffs, it may all be alte wurst. For me, it was a new approach to a familiar topic.**

*One of a long string of red-haired literary rebels and misfits who inspired and comforted a certain red-haired history buff as a child.

**I’m beginning to see a theme here. Sometimes I think I know nothing at all about history.

Love your blog!

Thank you!