Talking About Women’s History: Four Questions and an Answer with Eileen Bjorkman

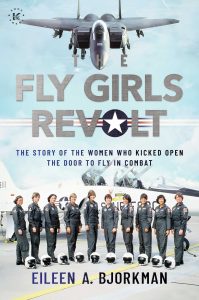

Eileen Bjorkman is a writer and retired Air Force colonel. She is the author of three books, including The Fly Girls Revolt: The Story of the Women Who Kicked Open the Door to Fly in Combat, which will be released in May. She has also had numerous articles and essays published in many outlets, including The Washington Post, Time.com, Air & Space, and Aviation History.

Take it away, Eileen!

What inspired you to write The Fly Girls’ Revolt?

I’ve read a lot of recent memoirs about women who have flown in combat in the past 20 years or so. And there are plenty of books about the Women Airforce Service Pilots in World War II, a group of about 1,000 civilian women who ferried military aircraft and did other support flying during the war. But there are almost no books about the women of my generation who served in the military in the 1970s and 1980s. This is the first generation of women who trained as military pilots, but could only fly support aircraft. These women led the charge to open the door in 1993 to allow women to fly combat aircraft. The full story that gives credit to everyone involved in making the change has never been told, so I wanted to tell that story. And the story isn’t just about women aviators; it’s about all the women who served and proved they belonged, along with those who supported them along the way, such as members of Congress and lawyers, including an unknown lawyer in the 1970s, Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

We’re all familiar with the challenges of finding sources for writing about women from the distant past. What are the challenges of writing about women from the late twentieth century?

The biggest challenge I had was finding materials in archives. A lot of material from that time period in military archives is still marked “For Official Use Only” or is still considered classified, even if the normal 25 year point for declassification has passed. I likely could have accessed some of the materials I wanted if I’d had time to file FOIA (Freedom of Information Act) requests, but I was on a tight timeline because I wanted to get the book published to coincide with the 30th anniversary of opening the door to combat in 1993. I’m not sure it made that much difference overall because I was able to learn much of what I needed by interviewing women, but some of the official sources would have been nice for fact checking and providing another perspective. Another challenge was that some of the archival material I used was recently donated and hadn’t yet been organized. I had to examine every single document in about a dozen boxes to see if it had any relevance to my research. I enjoyed looking at all the documents, but again, I was short on time, so some better organization might have helped. Last, a lot of the archival materials had maiden names in them, so I sometimes had to chase down who was who and what their current name was if I needed more information or wanted to check something. Fortunately, the Women Military Aviators association was able to help me find most of the women.

Did your own experience as a military aviator shape the writing of The Fly Girls’ Revolt?

Yes, definitely. I was a flight test engineer, not a pilot, and because of that, I was able to fly in the back seat of fighter aircraft because the airplanes we used for testing weren’t considered combat aircraft. From my own experiences, I knew that women were fully capable of flying combat aircraft, so I was a big proponent of opening the door, even though it didn’t impact me personally. I followed the news on women aviators very closely, and I knew some of the women who were working hard to get into combat. Knowing the basic story and some of the women helped shape my research from the beginning, as I knew which events I wanted to cover. I of course discovered some other things during my research that I included, but knowing the basic outline helped me focus. I also knew that I wanted to put myself into the story in a few places since I had the experience of being one of a handful of women who flew in fighters before it was allowed. I wanted to talk about some of the issues I encountered, as well as my ability to navigate the fighter and test pilot cultures to be part of the team.

What was the most surprising thing you’ve found doing historical research for your work?

I’d have to say it was learning that some things were not exactly the way I remembered them from the 1980s. I had some misperceptions about the Reagan administration’s attitudes towards women in the military because of what I’d observed as a young woman. I found during my research that I was wrong. I also learned things about one of the main characters that led me to write about her in a different way than many writers have previously. Having access to original source documents was very helpful in changing my mind about how to portray certain events and people. I think the biggest lesson learned is that, even if you’ve lived something, you still need to do research!

A question from Eileen: Why is it important to tell the stories of historical women today?

It’s really pretty simple. In her book, Headstrong, journalist Rachel Swaby describes the process of treating historical women scientists as scientists rather than anomalies or moonlighting wives and mothers as “revealing a hidden history of the world.” That’s true whether you are talking about scientists, or activists, or aviators, or journalists, or artists, or factory workers. When you put half the population back into history, you get a very different story.

* * *

Want to learn more about Eileen and The Fly Girls’ Revolt?

Check out her website: https://eileenbjorkman.com

Follow her on Twitter: @AviationHistGal

Follow her on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AviationHistGal/

* * *

Come back tomorrow for Three questions and an answer with historian and activist Elisabeth Griffith

Eileen-the next time you need help reading boxes of documents for information I would love to help. It was an amazing time when we had our first female test pilot student, and then shortly after a female pilot student was selected as the first female pilot astronaut. Progress continued when the first female combat fighter pilot was selected for a class. Anytime you need help give me a call.