Gertrude Whitney–A Guest Post by Rebecca Bratspies

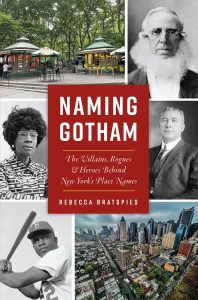

Rebecca Bratspies is a longtime resident of Astoria Queens. When not geeking out about New York City history, she is a Professor at CUNY School of Law, where she is the founding director of the Center for Urban Environmental Reform. A scholar of environmental justice, and human rights, Rebecca has written scores of law review articles. Her most recent book is Naming New York: The Villains, Rogues and Heroes Behind New York Place Names. Her co-authored textbook Environmental Justice: Law Policy and Regulation is used in schools across the country. Bratspies is perhaps best known for her environmentally-themed comic books Mayah’s Lot, Bina’s Plant, and Troop’s Run, made in collaboration with artist Charlie LaGreca-Velasco. These widely adopted comic books bring environmental literacy to a new generation of environmental leaders.

Rebecca serves on NYC’s Environmental Justice Advisory Board, and EPA’s Children’s Health Protection Advisory Committee, is a scholar with the Center for Progressive Reform and a member of the NYC Bar Environmental Committee. ABA-SEER honored her work with its 2021 Commitment to Diversity and Justice Award. She was named the Center for International Sustainable Development Law’s 2022 International Legal Specialist for Human Rights Award, and her environmental justice advocacy has been awarded the PSC-CUNY “In It Together” Award, and the Eastern’ Queens Alliance’s Snowy Egret Award.

Today she’s sharing one of the many stories of unexpected or forgotten New Yorkers from her book, Naming New York: The Villains, Rogues and Heroes Behind New York Place Names.

Take it away, Rebecca!

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875-1942) was a woman ahead of her time. As the eldest daughter of the eldest son of the richest family in American (her parents were Cornelius Vanderbilt II and Alice Claypoole Gwynne) she was heiress to a vast fortune. She grew up in an opulent 137-room Fifth Avenue mansion, attended the Brearley school, and spent summers at the Breakers—the family’s massive Newport Rhode Island summer home. But, from an early age, it was clear that Gertrude’s ambitions did not fit neatly into the society life scripted for “Miss Vanderbilt.”

As a child, Gertrude longed to be a boy. She went so far as to cut off her hair, an act she described as an attempt to rid herself of the main difference she saw between herself and her brothers. She was punished severely. As she grew into a teen and a young adult, Gertrude’s diary revealed her torment over the idea that people only pretended to like her because of her wealthy family.

As a young woman, Gertrude shared a romance with Ester Hunt, daughter of architect Richard Morris Hunt. In her journal, Gertrude wrote “I loved her more yesterday afternoon than I have ever done before. I felt more thrill at her touch, more happiness at her kiss.” Gertrude’s disapproving mother forbade her to see Esther and began a campaign to launch Gertrude into New York society, surrounding her with young men deemed eligible.

The strategy seemed to work, Gertrude was rapidly married off to the boy next door—the wealthy, well-connected Harry Payne Whitney. The two had virtually nothing in common and led mostly separate lives. Harry was a sportsman, who cared mostly about horses, playing polo, and hunting. Gertrude was an artist, in fact a sculptor. Gertrude and Esther continued a steamy correspondence until Esther’s death in 1901.

Gertrude had to fight to be taken seriously as an artist. Drawing and painting were considered appropriate activities for young women of her class (at least until they had children) but only as a mild kind of hobby. Neither her husband nor her family supported her artistic ambition and the wider world continually reminded Gertrude that serious art “wasn’t done by people in my position.” And, regardless of social class, women were definitely not supposed to sculpt.

Concerned that her society name and her female gender would brand her a dilettante, Gertrude did her earliest work under a pseudonym. But after her (male nude) sculpture Aspiration was selected for the 1901 Pan-American Exposition, Gertrude began working under her own name. She proved to be a talented sculptor, and her work was exhibited in major art shows across the country.

During World War I, Gertrude personally funded the construction and staffing of a 225-bed hospital just behind the front lines in France. During the Winter and spring of 1914-1915, she frequently visited the hospital, bringing supplies, assisting the administration, and sketching the patients.

After the war, Gertrude translated those wartime experiences into her art. She sculpted the Washington Heights War Memorial at 168th St and Broadway, panels for the New York victory arch, and a statue in St. Nazaire, France where the first contingent of the American Expeditionary Force landed. She also designed a massive cubist Columbus statue in Huelva Spain. This statute towers 114 feet over the harbor that launched Columbus’s 1492 voyage. She viewed these statues as “links which will serve to bind Europe and the United States even closer.” Her last sculptures were a Monument to Peter Stuyvesant, and Spirit of Flight, commissioned for the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing Meadow.

Gertrude’s best work is generally considered to be her design for the 1922 Titanic Memorial. The dramatic statue of a partially clothed young man standing with arms spread wide likely inspired the iconic scene in the 1997 Titanic movie. For Gertrude, this project was extremely personal because her older brother Alfred had died in similar circumstances with the 1915 sinking of the Lusitania. The Titanic memorial, which was unveiled by First Lady Helen Taft in 1931, bears an inscription dedicated “to the brave men who perished in the Titanic. They gave their lives that women and children might be saved.” This inscription makes it clear that the statute was intended to commemorate the first-class male passengers who died in the wreck, conveniently forgetting the scores of women and children, mostly traveling third-class, who also died.

Early in her career, Gertrude scandalized New York society by setting up her art studio at 19 Macdougal Alley in Greenwich Village. Headlines blared Daughter of Cornelius Vanderbilt Will Live in Dingy New York Alley. Nevertheless, Whitney built her studio, and apparently enjoyed a riotous bohemian lifestyle there—a sharp contrast to her otherwise aristocratic uptown existence.

Over time, Gertrude purchased the entire block of Macdougal Alley and turned it into the Whitney Studio club. She used the space to host exhibits, shining a spotlight on young artists like Edward Hopper, Robert Henri, Georgia O’Keefe, and George Bellows. She was a strong supporter of avant garde art, particularly the Ash Can School. Gertrude supported promising young artists with housing and stipends, and often purchased their work. She made a special point of supporting women artists.

Gertrude amassed an enormous collection of American art. In 1929, she offered to donate most of this collection to the Metropolitan Museum of Art—along with a $5 million endowment. The Met infamously declined the gift. Whitney responded by turning the Whitney Studio into the Whitney Museum of American Art, the first museum dedicated to contemporary American art. Today the Whitney possesses the world’s largest collection of American Art.

Gertrude’s work won her significant recognition. She was awarded honorary degrees from Russell Sage College, Rutgers University, Tufts, and NYU. She was awarded the French Legion of Honor in 1926, and perhaps most surprisingly was named to the National Dairy Association National Honor Roll in 1941 for developing a herd of 14 cows that produced 427 pounds of butter.

Gertrude died on April 18, 1942. She was 67 years old.