Jane Matilda Bolin: Another Guest Post by Rebecca Bratspies

I am delighted to have Rebecca Bratspies back with another story about a woman who deserves to be remembered.

On July 22, 1939 Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia appointed Jane Matilda Bolin to the New York City Domestic Relations Court (now the Family Court). This made Bolin the very first Black woman to serve as a judge in the United States. (LaGuardia was himself the first Italian-American to serve in Congress, and the second to be a mayor of a major US city. )

The appointment reportedly came as a surprise to Bolin. She was just 31 years old and had been working for the last two years as a lawyer assigned to the Domestic Relations Court on behalf of the City. On the fateful day, Mayor LaGuardia summoned Bolin, along with her husband and fellow attorney Ralph Mizelle, to the City of New York Building at the 1939 World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens. Bolin in fact thought she was about to get a reprimand of some kind. Instead, LaGuardia held a swearing-in ceremony.

LaGuardia emphasized that Bolin’s appointment, like all his other appointments, was made based on merit. While “merit” has recently become a code-word for anti-diversity efforts, LaGuardia meant the phrase differently. He was stating that the lack of Black officials was due to racism, and that merit-based appointments were an antidote to racial discrimination. Black newspaper coverage of her appointment repeatedly emphasized that Bolin was not appointed because of her race or gender, but in spite of them. There is no question she was eminently qualified.

The New York Times reported her judicial appointment under the headline “Negress Takes Oath of Office.” The Washington Tribune ran the story under the heading “Jane Bolin is Gotham’s First Woman Judge” with the subheading “Wife of D.C. Man Gets Job Paying $12000 yearly for 10 years.”

The pressure on Bolin to “make good” must have been immense. For her first twenty years on the bench, she was the ONLY Black woman judge in the United States. It was only in 1959, with Juanita Kidd Stout’s appointment to the municipal bench in Philadelphia, that Bolin had any company. (For perspective on how recent this all is, Jane Bolin was only two years older than my grandfather, her son is the same age as my mother.)

Before Judge Bolin made history as the first Black woman judge in the United States, she broke through many other barriers.

Bolin held degrees from Wellesley and Yale. Both institutions now proudly claim her, though her experiences at Yale and Wellesley were fraught with racial and gender-based hostility.

At Wellesley, Bolin was one of two Black students. (She had originally hoped to attend Vassar, but was rejected her because of her race.) Even though Wellesley admitted her, the school barred Bolin from living in the dorm with her white classmates. Bolin was forced to find housing off-campus.

Bolin graduated 1928 as a Wellesley Scholar, an honor given to the top 20 students in each graduating class. Despite her academic excellence, Bolin’s college counselor discouraged her from pursuing law school because she was Black. Even her father, himself a lawyer, tried to dissuade her from attending law school, though his concerns stemmed from his belief that women should be shielded from the seamier side of life.

But Bolin had grown up around the law, spending time in her father’s law office, and his shelves of leatherbound law books. Moreover, articles and photos of lynchings published in NAACP’s magazine The Crisis had shocked Bolin to her core, and inspired her to law school, and to public service.

Bolin persisted and after graduating Wellesley, she matriculated at Yale. She was one of three women and one of two Black persons attending Yale Law. Bolin remembered some of her fellow students taking delight in slamming doors in her face. Bolin reminisced that years later, after she was a judge, one of those very students later invited her to speak to his Texas ABA group. She declined.

Despite the hostile climate, in 1931 Bolin became the first Black woman to graduate from Yale. She was admitted to the New York Bar in 1932, and became the first Black woman to join the New York City Bar association. Despite her record of excellence, Bolin struggled to get a job. “I was rejected on account of being a woman, but I’m sure that race also played a part.”

In February 1933, Bolin and fellow attorney Ralph Mizelle married in secret for {reasons] (I don’t know what they were but I am confident they had some). Two years later, Bolin and Mizelle announced their marriage to the world and moved in together in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan. They briefly practiced law together though Mizelle soon became an assistant solicitor for the Post Office. In 1936, Bolin unsuccessfully ran for State Assembly as a Republican. The next year, she fought racial and gender discrimination to obtain a position with the New York City corporation counsel, the City’s legal department.

This job thrust Bolin into the public limelight. The Black press portrayed it as a significant racial advancement for Black people. Black newspapers began including Bolin on the list of heroes, alongside luminaries like Marion Anderson, Joe Lewis, Gwendolyn Brooks, Richard Wright, and George Washington Carver.

Fun Facts: In 1943, Bolin was part of the committee that welcomed fellow Wellesley graduate Madame Chiang Kai-Shek to Madison Square Garden. The committee chair was John D. Rockefeller Jr. In 1944, Bolin was named as one of Vogue Magazine’s “Women of the Year,” and in 1949 Ebony Magazine featured Bolin on its cover. In 1958, Bolin was included in Who’s Who of American Women.

Judge Bolin was a trailblazer on many work/life issues women still struggle to navigate today. Even though she was married to Mizelle, she continued to use her own name. Newspapers routinely referred to her as “Miss Bolin” (widespread use of the term Ms. only happened when another New Yorker, Geraldine Ferraro, became the Democratic candidate for Vice President of the United States.) Moreover, Mizelle and Bolin had a commuter marriage—he worked in D.C. while she was in New York City. She took maternity leave for the birth of her son Yorke Bolin MIzelle, and then went back to work.

As a judge, Bolin helped racially integrate the city’s child services, ensuring that probation officers were assigned without regard to race or religion, and that publicly funded childcare agencies served children without regard to ethnic background. Although widely respected for her judicial temperament, Bolin did not hesitate to call out racism. She issued subpoenas for police officers accused of beating a Black teenager on his way to school. She wrote a letter to President Roosevelt urging him to support anti-lynching legislation. When her hometown Poughkeepsie feted her as a local hero in the 1940s, she called the segregation in the town’s schools, hospitals, and government “fascist,” and criticized the town for “deluding itself that there is superiority among human beings by reasons solely of color, race or religion.”

In 1966, 27 years after Bolin was appointed to the New York court, Constance Baker Motley became the first Black woman appointed to a federal bench. Both Constance Baker Motley and Judith Kaye, the first woman to serve as Chief Judge of the NY Court of Appeals, cited Bolin as a role model and a resource. President Biden made history when he nominated Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson to the United States Supreme Court in 2021. Brown Jackson was confirmed by the Senate on April 7, 2022, making her the third Black person to serve as an associate justice and the first Black woman. (Of the 117 justices to serve on the Supreme Court, only 6 have been women and only 3 have been Black.) The ugly slurs directed at Justice Brown Jackson in 2021, in terms of her abilities and qualifications, might give a slight window into what Judge Bolin undoubtedly navigated daily.

Judge Bolin remained on the bench for 40 years, only retiring when she hit New York’s mandatory judicial retirement age of 70. The Judicial Council of the American Bar Association honored her for her service. Even after retiring, Judge Bolin continued to serve on the boards of the NAACP, the National Urban League, and the Child Welfare League. She was also a member of the Regents Review Committee of the New York State Board of Regents.

Every legislative session since 2017, New York state Assembly member Jeffrion Aubrey has introduced a bill in the NY State Assembly to rename the Queens–Midtown Tunnel the Jane Matilda Bolin Tunnel in her honor. Count me on Team Name It For Bolin! I cannot think of anyone more deserving of this kind of honor!

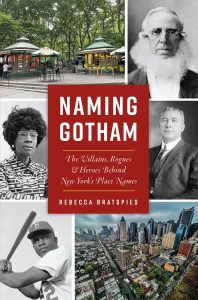

Rebecca Bratspies is a longtime resident of Astoria Queens. When not geeking out about New York City history, she is a Professor at CUNY School of Law, where she is the founding director of the Center for Urban Environmental Reform. A scholar of environmental justice, and human rights, Rebecca has written scores of law review articles. Her most recent book is Naming New York: The Villains, Rogues and Heroes Behind New York Place Names.

Big Fun!