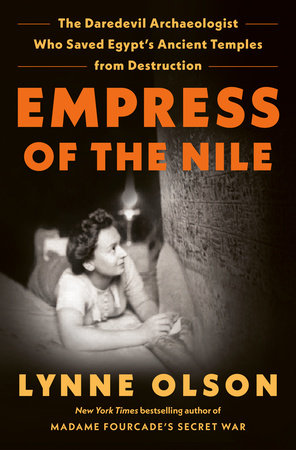

Empress of the Nile

I am a fan of Lynne Olson’s work. I am also a lifelong archeology nerd. So when I first saw an notice about Olson’s newest book, Empress of the Nile: the Daredevil Archeaologist* Who Saved Egypt’s Ancient Temples from Destruction, it was an automatic pre-order.**

Empress of the Nile was also the first book I picked to read from the ever-growing To-Be-Read pile once I had some time to read non-fiction that was not related to the book I am working on.

I must admit, I have mixed feelings about the book. As always, Olson does an excellent job of weaving her story into its historical background, in this case, the history of Egyptology in France,*** ancient Egyptian history, the French resistance in World War II, Egyptian nationalism, and the early years of UNESCO.

At the same time, the book doesn’t entirely deliver on the story promised in the title.

The first section of the book deals with Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt’s early career as an Egyptologist. This section included her challenges as a woman in the man’s world of French archaeology, her work in the field in Egypt, her involvement in an unlikely resistance network during the German occupation of France, and her role in saving the Louvre’s art and artifacts from the Nazis during World War II. This was exactly the type of material I expected from the title and Olson had me turning pages as fast as I could go.

The second, and largest, section covers the international effort to save Egyptian monuments in Nubia, particularly the temples at Abu Simbel, from being destroyed by the construction of the Aswan High Dam. The story is interesting. Olson traces the diplomatic games required to fund the rescue project and the related infighting between various archaeological organizations and museums and describes the heroic blend of engineering and archeaology involved in relocating the monuments. But she loses track of Noblecourt for much of the story. She tells how Noblecourt kicked off the effort, refusing to simply accept that the structures must be lost. Moving forward, Olson repeatedly states that Noblecourt was a critical player in saving the structures. But she doesn’t really show the archaeologist’s involvement. Instead she focuses on Jacqueline Kennedy’s role in getting the United States to commit to the UNESCO project. Definitely interesting, and it made want to know about the former first lady.

In the final section, Olson returns to Noblecourt’s career.

Each of the sections is interesting, but the narrative structure doesn’t hold together because of Noblecourt’s repeated absence in the middle.

Bottom line, I enjoyed the book, but not as much as I expected. Dang.

*Spell check doesn’t like that extra a, but the books about archaeology that I read as a nerdy little girl who dreamed of working on digs all spelled it that way and I do, too. (And in this case, so does Random House.)

** For those of you who don’t know, publishing industry wisdom is that pre-orders are good for books and authors. Pre-orders tell publishers and retailers that people are interested in the book, in theory generating early buzz which help sells more books. If you plan on buying a book anyway, pre-ordering it from your preferred book purveyor is a way to help the author. (Does it actually work? I don’t know.) I also think of it as buying future Pamela a surprise present because I often forget I’ve ordered it. (And yes, this does mean I occasionally pre-order a book twice, thereby getting an unintended step forward on Christmas shopping.)

***A fascinating story with ties to Napoleon’s attempts to conquer Egypt.