From the Archives: City

My editor has come through with revision notes for Sigrid Schultz and I am deep in the eternally fascinating process of seeing my book through someone else’s eyes. (And since I’ve had a couple of months away from the book, I’m also seeing things I want to revise that she hasn’t called out.) I’m making structural changes, taking stuff out, and adding stuff back in. I’m stepping back to get the big picture and focusing in at the sentence level. (In one case I have two succeeding sentences with the same, very specific format. My editor didn’t point it out, but it jumped out at me as I read. Frustrating because there is nothing inherently wrong with the sentences qua sentences and my brain is not letting them go without a struggle. I keep chanting “Kill your darlings,” but it isn’t helping.)

As a result, I am having trouble writing a new blog post. So, here’s one more from the archives:a book review that originally ran in 2012. As you can no doubt tell, I really liked the book. In fact, I just pulled it off my shelf for a little re-reading.

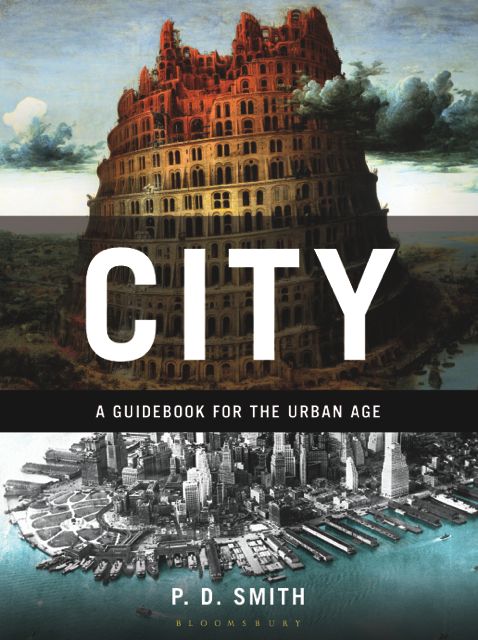

Cultural historian P.D. Smith argues that the city is humanity’s greatest creation. After reading City: A Guidebook for the Urban Age, it’s easy to believe it’s true.

City is not a simple chronological history of urban areas from their first appearance in ancient Mesopotamia to modern megacities. Instead, Smith organizes his work around elements of city life that “have become part of our urban genetic code”: cemeteries, street protests, slums, suburbs, markets, street food, graffiti. He draws illuminating parallels and unexpected connections. The chapter titled “Where to Stay”, for example, begins with the growth, death and rebirth of downtown, looks at immigrant neighborhoods in nineteenth century America in the context of Jewish ghettos in Europe, makes a sharp turn to slum cities in the developing world, considers the allure of garden suburbs beginning in ancient Babylon, and ends with a brief history of the hotel.

The book is punctuated by sidebars that go off at right angles to the main text. A brief history of the parking meter accompanies the section on commuting. The hanging gardens of Babylon are discussed in the context of urban parks.

Smith’s range of material is breathtaking, but he wears his erudition lightly. The prose of City is smart and fast-paced, with a nice balance between big picture history and close-up details. The book is full of “aha” moments and occasional humor. I can’t imagine a history fan who won’t find at least one section fascinating.