World War II in Sicily

We spent one night in a renovated vineyard/ “farm stay” hotel that dated from the eighteenth century. The vineyard operated continuously through World War II, when it was abandoned. It was reopened in 2000. When I asked our Sicilian tour leader why it had been abandoned, he shrugged and said “So many possible reasons.” The war had been hard on Sicily.

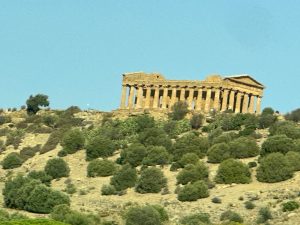

Not surprisingly, World War II was not a focus of our visit. (As I’ve mentioned, several times before, the tour focused on food.) And yet it was never far away. Our guide in Palermo pointed out concrete apartment buildings in the historic district of Palermo— built during a brief period in the 1950s as post-war replacements for the baroque-style villas that were destroyed in 1943 when both the Germans and the Allies bombed Sicily. In Siracusa, we learned that Mussolini razed medieval and baroque buildings to clear a path for his parade through the city. (I’ve not been able to verify this, but there is definitely a swath of ugly post-war concrete buildings through the historic district.*) And German pillboxes scatter the countryside near the coast, much like the Grecian ruins which we saw on many hilltops—a reminder of the past without a specific context.

Faced with constant physical reminders of the war, I began to realize that I didn’t know much about World War II in Sicily. Back home, I set out to learn more. (Does this surprise anyone?) I quickly realized that unless you look at something specifically focused on Sicily, its role in the war is often described as “the doorway to Italy.” In fact, one reference book on my shelf summed up 38 days of hard fighting for control of the island this way: “The Allied invasion of Sicily began on July 9, 1943, and the battle for Italy followed.”

In fact, the Allied invasion of Sicily, known as “Operation Husky,” was a major amphibious operation that gave the Allies a preview of many of the issues they would encounter a year later in the D-Day invasion. More than 3,000 ships landed 160,000 soldiers— the combined forces of British General Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army and the US Seventh Army under General George Patton. (Not a pair inclined to play well together.) They were covered by 4,000 aircraft from Malta. More would follow

The Nazis believed that the Allied attack would focus on Sardinia and Corsica, thanks to an elaborate misinformation campaign run by the British, known as “Mincemeat”.** As a result, only two German divisions were on the island to oppose the invasion. The German commander, and subsequent historians, dismissed the Italian forces as being of little help—an assessment that may well have been accurate due to Italy’s political instability.

On July 24, Benito Mussolini was deposed and arrested. The new Italian government immediately sued for peace with the Allies and withdrew their troops from Sicily the next day. Germany, too, began to withdraw troops across the Messina Straits in order to reinforce their forces in mainland Italy.

Over 38 brutal days, half a million Allied soldiers fought over rocky terrain through at least three defensive lines of the German retreat. The Allies reached the port city of Messina on August 17. They now controlled Sicily, the first section of the Axis homelands to fall to Allied forces in the war and a strategic key to the Mediterranean.

*It is only fair to note that not all post-war concrete buildings, in Sicily and elsewhere, are ugly. Siracusa, for instance, has several stunning examples of Brutalist architecture from the 1950s.

**Has anyone written about who named the various Allied campaigns and why they chose the names they did?