Talkies, or “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet”

Recently I’ve been dipping into the early days of talking pictures. As usual, a very specific question led me down unexpected rabbit holes. For once, I wasn’t surprised by the depth of my ignorance. Everything I knew about the first “talkies” came from the film Singin’ in the Rain—a movie that I love but that I assumed was not a good historical source.*

Here are some bits that caught my imagination:

- The Jazz Singer (1927), which in the shorthand version of film history is considered the first commercial talking picture, in fact used elements of both silent and talking pictures. Recorded using “sound on disc” technology, the sections of the film that included sound were relatively short, and were mostly devoted to Al Jolson singing—an obvious intermediate step between phonograph records and silent movies. The recordings also caught several improvised comments by Jolson, which the director chose to keep in the final soundtrack and which generated much of the excitement about the film. In my opinion, one of those lines sums up the place of The Jazz Singer in film history: “You ain’t heard nothing yet!” I can’t help but wonder if Jolson wasn’t thinking of the process of making films when he said it.

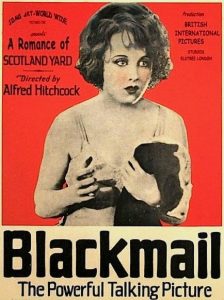

- Singin’ in the Rain used one piece of “talkie” history to great affect, revealing one of early Hollywood’s technical secrets in the process. To my surprise, the use of aspiring actress Kathy Seldon (Debbie Reynolds) to dub the lines for silent film Lina Lamont (Jean Hagen) because Lamont’s voice was, let’s just say unpleasant,** reflected a real technique used when silent film actors attempted to make the leap to sound. The technique was used not only to cover for voices that were too shrill, too nasal, too soft or just, “too,” but also to hide strong European accents. Only two years after The Jazz Singer, Alfred Hitchcock used the technique effectively in Blackmail (1929), in which actress Joan Barry dubbed lines for Czech Anny Ondra, whose accent was considered unacceptable for English-speaking audiences.***

- Introducing sound into movies using the first viable “sound-on-disc” and “sound-on-film” technologies**** forced movie makers to find a way to mask unwanted sounds. Ironically, the biggest problem was the sound of the cameras themselves. At first cameras were isolated in heavy sound-proof cabinets, sometimes called “iceboxes,” to mute the sound of their motors, which limited directors’ ability to move their cameras. I don’t remember seeing such a thing in the on-set scenes in Singing in the Rain. Perhaps it’s time to watch it again?

*Though in fact, Singin’ in the Rain came out only 25 years after The Jazz Singer, something I hadn’t realized until I went down this particular rabbit hole. The film’s creators may have known more about movie history than I gave them credit for.

**In an interesting twist, Hagen “dubbed” her own spoken lines. .

***This surviving clip of a sound test with Hemingway makes it clear that her accent was, in fact, quite light. (It also makes clear that Hitchcock was a bit of a jerk.)

****Sound-on-film ultimately won, but for a time movies were produced in both formats to accommodate the fact that theaters had different set-ups. During this period, some studios also produced parallel silent versions of films because smaller theaters were slow to catch up.