In which I consider the nature of primary sources, with a little despair

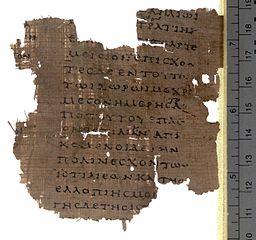

Fragment of Herodotus’s Histories

My primary academic home is the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries,* periods in which primary sources and material artifacts are relatively abundant. As a result, the question of whether something counts as a primary source is generally clear–at least in terms of a given sources’s temporal relationship to the event/period in question.** (How we use sources and the type of sources admitted to the canon are constantly evolving topics as the subjects we consider worthy of historical consideration expand.)

Recently I’ve been playing in time periods that are definitely Not My Field and I’ve been forced to consider the question of what constitutes a credible source when written sources are limited. Here are three examples that I have struggled with over the last few weeks:

- The story of Queen Tomyris, who defeated Cyrus the Great of Persia in 530 BCE. Our principle source for this is a brief report by Herodotus, who wrote his Histories roughly 100 years later. This is equivalent to my blog post about the beginning of World War I being the only surviving source for that conflict in 5090.

- We have a little more information in the case of Queen Boadica, who led a rebellion against the Roman occupation of Britain in 61 CE: two written sources (both Roman) and some archaeological confirmation. The Roman historian Tacitus, who was born five years before the revolt, wrote two separate accounts of Boudica’s rebellion. He could at least claim second-hand knowledge of the events on which he reported: his father-in-law served as a member of the Roman governor’s staff during the revolt and there is evidence that Tacitus interviewed other veterans of the rebellion. Our only other source is part of an account written roughly a hundred years later by Dio Cassius, which appears in a selection of readings compiled by a Greek monk in the eleventh century.

- Most recently I’ve been working on Assyrian reliefs that document the Assyrian conquest of Lachish, the second most important city in the kingdom of Judah, in 701 BCE. What we know about the event comes from a complicated interplay between Assyrian inscriptions, a blurb in our old friend Herodotus, the reliefs themselves, archaeological evidence from ruins that have been identified as Lachish and the accounts of the invasion, siege, and conquest in the Old Testament.***

My only conclusion: The winner may write history in the short run–if by short run you mean over the course of 300-400 years and assuming you write the kind of history in which there is a winner). But in the long run, time itself edits history with the help of nibbling rodents, grinding sand, fire, water, and the occasional military rampage. I bow my head to those who untangle the distant past from not much data.

* With occasional forays into the medieval and early modern periods, where the nature of primary sources is a little fuzzier. Possibly the most famous example of a dodgy flexible use of sources for the early modern period is the common use Sir Thomas More (1478-1535) as a primary source for the reign of Richard III, which lasted from 1483 to 1485. I don’t know about you, but I’m not a credible source for historical events that occurred when I was five to seven years old.

**Whether a given source is reliable is a different question entirely.

***I must admit, I have a hard time wrapping my head around using the Old Testament as an historical document. It stops me short every time one of the secondary sources I’m reading quotes a passage of Kings or Isaiah the same way I would quote a nineteenth century newspaper clipping.

I do so agree with you! So much of what we think of as “facts” of ancient history are based on what we would consider to be unreliable sources if they were used these days to support an argument about more recent events. There is a tendency to telescope periods between dates when they are both so far removed from us.

Josephine Tey’s The Daughter of Time is wonderful on the use of Thomas More as an authority on Richard III. If I remember correctly, her detective Grant says that the book was actually written by John Morton, Henry VII’s Archbishop of Canterbury, and More just copied it i.e. literally wrote in manuscript a copy of it because he admired it and that was how he could have his own copy.

If this is correct then it overcomes the problem of the author not being contemporary with Richard III. However, Morton was an opponent of Richard III, imprisoned by him, and famously a supporter of Henry VII who usurped Richard III and (per Tey) had a much better motive for murdering the Princes in the Tower. So a different issue, that of objectivity, arises.

Objectivity is a different issue indeed. I tend to work on the assumption that no one in the evidence chain is objective–me included. The best you can hope for is identifying a source’s biases (for want of a less loaded word) and use those biases as a different kind of information.