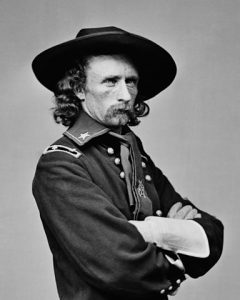

From the Archives: Custer’s Last Stand?

On June 25, 1876, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer and five companies of the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry died at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

Unlike D-Day, it’s not the kind of historical event that generates lots of anniversary coverage. (Though I suspect it will garner some attention on its 150th anniversary in 2026.) And up until a couple of hours ago I had no intention of re-running this post from 2016. But I’ve spent several hours struggling with a new blog post that just isn’t working–a losing skirmish of a different sort. Sometimes it makes more sense to make a graceful retreat than to fight to the deal.

And so I offer you a few thoughts on Custer’s defeat and how we report on historical events. I think they hold up three years after I first wrote them.

* * *

Sometimes I think that no matter how much we may know about history as individuals, collectively we know nothing at all.

Case in point: Custer’s Last Stand.

I am currently working on an article that is about a painting about the event that you and I have always known as Custer’s Last Stand.(1) I went into the piece with only the vaguest sense of the historical event, something I felt no shame about because American history is not my field. Here is what I had going in:

- Custer was a Civil War hero, and as problematic after the war as that other Civil War hero, Ulysses S. Grant. Though not the same way.

- A small group of soldiers under his command died fighting a large group of Native Americans at the Battle of Little Big Horn

- A vague sense that Custer was at fault(2)

- A certainty that it must have been a critical battle, because otherwise why would I have heard about it?

- It occurred after the American Civil War, during the period when the west was “opened”.(3)

None of that is completely wrong. Except for the part about it being a critical battle. It wasn’t. Whether you think the death of the Seventh Cavalry at the Little Big Horn on June 25, 1876 was a military blunder or an act of heroism–or both(4)– the battle changed nothing. It was barely a battle, even by nineteenth century standards. It had no lasting effect on the so-called Indian Wars, or on the drawn-out dreary campaign of which it was a part. The Sioux won the battle, but gained nothing by their victory.

The battle/fight/skirmish is historical fact, but it turns out that the popular image of that skirmish as a “last stand” is an artist’s creation, reinforced by other artists’ creations over the last 140 years. And the power of that largely mythical image is one reason an otherwise meaningless military encounter became, and remains, an important emblem of a ugly struggle that stands at the root of America’s westward expansion.

When it comes to the the Battle of Little Bighorn, we don’t actually know what happened and the question of whether Custer showed poor judgment continues to be hotly debated among those who care. The Seventh Cavalry, under Custer’s leadership, was intended to be one prong of a three-pronged campaign to encircle the Sioux and drive them from their treaty territory. When Custer’s scouts reported the discovery of a Sioux village, Custer divided his forces into three parts, keeping only five companies with him to face what turned out to be a much larger force than the US Army had originally estimated. Companies under the leadership of Captain Benteen and Major Reno retreated to a defensive position on the bluffs rather than attacking an overwhelming force. As for Custer, the last thing we know of him is his often-quoted final message: “Benteen. Come on. Big village. Be quick. Bring packs. W.E. Cooke. P.S. Bring packs.” According to Trumpeter John Martin, who carried the message, Custer was about to charge the village as Martin left.

This is the point at which traditional histories often say that no one survived the battle. In fact, hundreds of people survived the battle–all of them members of the Sioux and Cheyenne nations. Some of them left their own accounts of the battle, but those accounts disagree about the actions taken by Custer’s troops. (This should come as a surprise to no one. Soldiers in the front line of battle seldom have a sense of the big picture.)

Maybe the battle, from the perspective of the 7th Cavalry, was a heroic last stand.(5) Maybe it was a rout. The one thing we can say for certain is that whatever happened, it probably didn’t look like this:

(1) If you’re interested, it appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of American History

(2) Almost a reflex for me. I was twelve in 1970, when Little Big Man hit the screen and Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee was released, The ironic Western and revisionist examinations of Native American history are deeply rooted in my brain. Possibly the first step in a career based on trying to walk in someone else’s historical shoes.

(3) A phrase that ranges from problematic to horrific. Once you start looking at a period of history with an awareness that there are two sides to every historical event you find linguistic pitfalls everywhere. I have no good answer for how to cope with this other than to type with my eyes wide open and carry a large bag of quotation marks.

(4) The two are not mutually exclusive. Think the Charge of the Light Brigade.

(5) According to the OED, a last stand is “an act of determinedly holding or defending a position against a (more powerful) opposing force; a final show of resistance or protest”. Wikipedia adds a few critical elements from the popular definition: the defensive force usually takes very heavy casualties or is completely destroyed and (most important for the rest of this discussion) the last stand is a tactical choice taken because the defending forced recognizes the benefits of fighting outweigh the benefits of retreat or surrender.