A Year in Review: 1519

Back in May, announcements of museum exhibitions celebrating the work of Leonardo da Vinci began to appear in the various places where I hang out online, triggered by the 500th anniversary of his death.(1) They made me wonder what else of note happened in 1519.(2)

It turned out that quite a lot was going on. (Go figure.) Here are some of the high and low points, in no particular order:

The Protestant Reformation was beginning to bubble. Martin Luther publicly questioned the doctrine of papal infallibility and was summoned to Rome on charges of heresy. In Zurich, Ulrich Zwingli was preaching his own brand of church reform, which would develop after his death into the various Reformed and Calvinist versions of Protestantism.

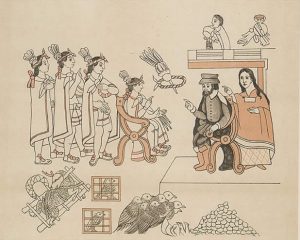

Hernán Cortés landed at Veracruz with a force of 550 men, sixteen horses, several mastiffs, and ten brass cannon. He assembled a coalition of native peoples who had previously been conquered by the Aztecs and marched on the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán. Because Cortes and the Spanish appeared to fulfill an Aztec legend about the return of the god Quetzalcoátl, the Aztec ruler Montezuma II met the Spanish with a warm welcome rather than armed resistance. In fact, he invited Cortés into the royal palace. Not a good decision. Cortés took Montezuma captive and used him as a hostage to subdue the Aztec people. That peaceful surrender wasn’t the end of the story. A year later, in Cortes’ absence, the Aztecs revolted. Montezuma was killed in the revolt. Cortes and his allies looted their way through the empire, succeeding in part because an epidemic of smallpox devastated the native population.

And speaking of forgotten women in history, as we so often do here in the Margins, there was another important character in this story who didn’t show up in the versions I learned in school: a multilingual Amerindian woman variously known as La Malinche, Doña Marina and Malintzin.(3) Her story has been pieced together over the years from conflicting accounts, with lots of holes in them. (Even the names we know her by date from her relationship with the Spanish.) She was the daughter of an Aztec (or possibly Mayan) chieftain, whose mother sold her to slavers after her father’s death. The slavers sold her to another chieftain, who presented her, along with a group of nineteen other young women, to Cortés in 1519. Most accounts of her story claim she became Cortés mistress, though I’m not sure that’s the correct term for an enslaved woman who is used sexually by her owner. Beyond their sexual relationship, Malintzin quickly became indispensable to Cortés as a linguistic and cultural translator, and possibly as a military and diplomatic strategist. She is often portrayed as a traitor, or at best a victim. (4) But at least one scholar, Cordelia Candelaria, suggests that Malintzin, too, may have been bedazzled by the possibility that Cortés was the god Quetzalcoátl. From slave girl to right hand of the god is a pretty big step.

In addition to smallpox, Cortés reintroduced horses to the Americas. Over time, horses would transform Native American cultures in the Western plains and Latin America. Going the other direction, he brought cacao beans to the Spanish royal court, along with instructions for turning them into a tasty beverage. Hot chocolate anyone?

The Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan sailed with five Spanish ships in search of a western route to the Spice Islands, the first step in circumnavigating the globe.

Finally, just to balance out the fact that this post started with the anniversary of a death, Isabella Jagiellion, the first ruler to issue an edict declaring universal religious toleration, was born on January 18, 1519.

Finally, just to balance out the fact that this post started with the anniversary of a death, Isabella Jagiellion, the first ruler to issue an edict declaring universal religious toleration, was born on January 18, 1519.

(1) Lucrezia Borgia also died in 1519, but no one seemed inclined to celebrate that anniversary. Though I would bet that 500 years ago a person or two may have lifted a glass in honor of the occasion. Assuming that the popular image of Lucretia bears any resemblance to reality. Which it may not because that’s the way it goes with women in history. (A quick poke around on line reveals titles such as “Lucretia Borgia: Predator Or Pawn?”—not a great pair of choices.)

(2) I am not the sort of historian who holds lots of random dates in my head.

(3) Or at least forgotten in the United States. She is definitely remembered in Mexico, where her name is an insult.

(4) Also not a great pair of choices.