Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin: Journalist, Abolitionist, Suffragist, Shin-Kicker

A hundred years ago, on August 18, 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment, which gave women the right to vote, was ratified. A lot of us planned to celebrate, in public and out loud. Many of those celebrations have been postponed for a year so we can party like it’s 1920.

Luckily, it’s easy to practice social distancing on a blog, so I will continue with my plan to run suffrage-related blog posts for much of the summer. Starting now.

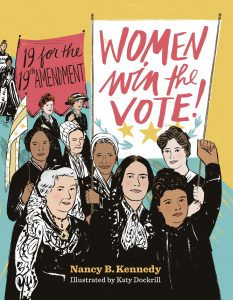

I am please to kick off my suffrage coverage with the story of an amazing suffragist I never heard of, courtesy of Nancy B. Kennedy. Nancy is the author of Women Win the Vote! 19 for the 19th Amendment, a lively illustrated biography of women—well-known and otherwise—who fought for the right to vote.

Take it away, Nancy!

In the mid-1800s, John St. Pierre married Elizabeth Matilda Menhenick. History doesn’t tell us when exactly, but they were quite the couple. John was a successful young businessman of French and African descent whose father came from Martinique. Elizabeth was a young Englishwoman from Cornwall who was descended from an African prince who married a Native American woman.

The couple were married in Boston, and in 1842 their sixth child, Josephine, was born. They named her after the Empress Josephine, the first wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, herself a native of Martinique.

Josephine traveled in Boston’s highest social circles. At age 16, she married George Ruffin, who went on to become the first African American man to graduate from Harvard Law School, the first elected to the Boston City Council, and the first appointed a municipal judge.

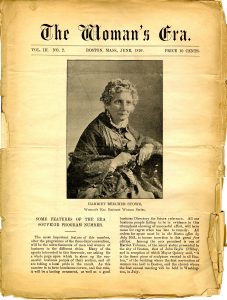

Josephine was a journalist who founded the Women’s Era newspaper, the first newspaper written by and for black women in the United States. She later became editor of the Boston Courant, a black weekly paper.

As my host Pamela Toler frequently reminds us, women are often relegated to the margins of history. So, with a lineage and resume like this, why don’t we know about Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin? Josephine was an ardent suffragist, and I was happy to learn about her when I researched my book, Women Win the Vote! 19 for the 19th Amendment.

Like many suffragists, Josephine came first to the abolition cause. After she married, the couple moved to England in protest of the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision ruling that African Americans had no claim to freedom or citizenship. But the Civil War soon called them back. Josephine helped recruit black soldiers for the Union and provided aid and care for them both during and after the war.

In 1869, she co-founded the American Women Suffrage Association with two white women, Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe. She was also a pioneer in the founding of black women’s clubs, which worked to improve the lives of African Americans. In 1896, she co-founded the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs.

Even so, Josephine is most known for a single moment in her life. In 1900, she attended a convention of the National Federation of Women’s Clubs in Milwaukee as a delegate of two Massachusetts women’s organizations. But she also represented the Women’s Era Club, an all-black women’s group she had founded along with the newspaper.

After Josephine pinned her delegate’s ribbon to her dress, a commotion arose. Federation president Rebecca Lowe, a delegate from Georgia, protested inclusion of the Women’s Era Club. The Southern clubs then threatened to withdraw if the Women’s Era Club was admitted. “It is the high-caste negroes who bring about all the ill-feeling,” Lowe groused. “The ordinary colored woman understands her position thoroughly.”

At that, someone stepped forward to rip the delegate’s ribbon from Josephine’s dress. She was having none of it! She gripped the ribbon firmly and fought off the attacker. Yet Josephine ultimately declined to participate in the convention, to protest the exclusion of the Women’s Era.

This ugly display of prejudice must have been crushing for Josephine. Here she had worked with suffrage pioneers Lucy Stone and Julia Ward Howe at a time when the movement was fully integrated. In fact, when Josephine started the Women’s Era newspaper, she chose as its motto, “Aim to make the world better” — words Lucy Stone spoke on her deathbed.

Sadly, racial bias continued to taint the suffrage movement. But Josephine always hoped for better. She publicly praised the white women who led it — the same women who were excluding her race. “The success of this movement for equality of the sexes means more progress toward equality of the races,” she wrote in 1915 in The Crisis, the magazine of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Women won the vote four years before Josephine died in 1924. She could have predicted the victory. She once said of the Women’s Era Club: “Being a woman’s movement, it is bound to succeed!” She might as well have said it about the woman’s fight for the vote.

Interested in learning more about Nancy and Women Win the Vote! ?

Check out her website: https://www.nancybkennedy.com/

Follow her on Twitter: @NB_Kennedy