Wrapping My Head Around the Weimar Republic, Pt 2: Born in Revolution

As I mentioned in a previous post, I went into my newest project a year ago with an astonishing degree of ignorance about the Weimar Republic. As I got into the reading, I was both shocked and embarrassed about how little I knew. And one of the things I didn’t know was how the Weimar Republic began. My best guess, had someone asked me, would have been that the Republic was established as part of the Versailles Treaty. (After all, both the Austrian and Ottoman empires were dissembled in the peace talks, creating the modern states of Austria and Turkey. Why not the Hohenzollern empire?*

I couldn’t have been more wrong.

In October, 1918, Germany’s old absolute monarchy was effectively dead, though Kaiser Wilhelm was still on the throne. The (relatively) liberally minded Prince Maximillian, appointed Imperial Chancellor, joined forced with the Social Democratic Party (SPD) to alter Germany’s constitution. Together they were in the process of creating a true constitutional monarchy and reforming electoral law. (In theory Germany had universal male suffrage before the war, but the man in the street wasn’t allow to vote for anything that mattered so it wasn’t worth much.)

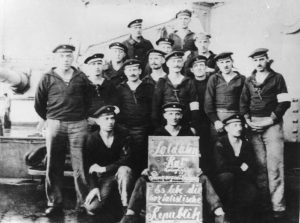

On October 29, the hope of an orderly transfer of power blew up in their faces when sailors in the port city of Kiel mutinied. Several days later, delegations of sailors traveled by railroad to big cities across the country, spreading the word of their revolt against the officers, stupid orders, the war, and the empire. By November 7, the mutiny turned into a rebellion, as striking workers and mutinous soldiers joined forces with the sailors. Borrowing from the Russian Revolution, the workers and servicemen elected councils that negotiated with local authorities. It was grassroots democracy in a country in which most people had no experience of political participation.

On November 9, Prince Maximillian, hoping to restore order, turned over the position of chancellor to Friedrich Ebert, the head of the SPD. Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated.**

The old Reich was dead, but the new Republic was on shaky ground. At 2 o’clock that afternoon, Philip Schiedemann, speaking for the new provisional government, proclaimed the end of the empire from the balcony of the Reichstag building to cheering crowds. Several hours later, Karl Liebnecht, a radical socialist leader, stood on the balcony of the royal palace, and proclaimed the creation of a socialist republic.

On November 11, Ebert and his colleagues formed a new government in coalition with the more radical Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD). (You caught that, right? Two governments in two days.) Despite the shaky start, the new republic began with a rush of political reforms. Spurred by the energy of the mass movements in the streets, they passed laws guaranteeing freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, suffrage reform (include suffrage for women!) and amnesty for political prisoners.

The Weimar Republic was on its way and things were looking good.

*Did I mention that the depth of my ignorance was embarrassing? I’m not even sure that old stand-by “not my field” is an excuse.

**Possibly with his fingers crossed behind his back. Royal attempts to regain power in Germany are a recurring theme in newspaper articles of the 1920s.

It is hard to take all this in in hindsight , taking that the fallow up was even worse. Give them what they want so quickly has never been a good idea ever. the catasraphy with Hindenberg and Hitler should have been the writing on the wall but for the many issues hanging in the Reichstag at the time and so few capable players to jump in to the fracas. The crystal ball was shattered and only what happened after was was unfortunately the result of the cumulative exasperation’s of the Laender (States) in the Bund (confederacy). I have read much on the topic all be it in German ad a clear picture will never be analyzed completely. your effort is a good start.