Wrapping My Head Around the Weimar Republic, Pt. 4: The Sparticist Uprising.

The Weimar Republic almost died soon after it began.

Conditions were bad in Germany during the first months of the Weimar Republic. Food and fuel shortages continued after the end of the war and many Germans were cold and starving. The economy was in disarray. Unemployment was high, as both the army and the industries that supported it were demobilized. The third-wave of the worldwide flu pandemic showed no signs of ending. And the imperial government had left the leaders of the new republic the humiliating and thankless task of signing the Versailles peace treaty, earning the nickname the “November Criminals”.

The Weimar Republic would go on to create an innovative and far-reaching social security net, but they had barely had time to get themselves organized when a small, determined group of Marxist revolutionaries made a bid to re-create the Russian Revolution in Germany.

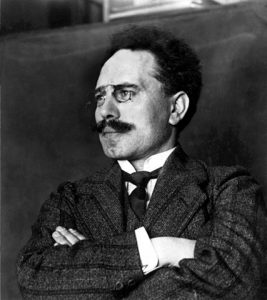

On January 5, 1919, a group who called themselves the Spartacists* staged an uprising against the Weimar republic, armed courtesy of the recently fired Berlin police chief, a radical sympathizer who provided the Sparticists with weapons. Led by “Red Rosa” Luxemburg and Karl Lieibknecht,** the Spartacists called for a general strike that brought thousands of demonstrators to the center of Berlin, where they erected barricades in the streets and seized the offices of socialist newspaper that was pro-Weimar and anti-Sparticist.*** They tried to get army regiments to repeat the glory days of the Kiel mutiny and join the revolt, with no success.

Instead of joining the revolt, the army and right wing volunteer militias**** attacked the revolutionaries with the full approval of Ebert’s cabinet. The army and the Freikorps re-captured the buildings the rebels had seized (including the police headquarters and the war ministry) and shot hundreds of the demonstrators, including many who had surrendered.

On January 15, a Freikorps unit captured Luxemburg and Liebknecht. They smashed in Luxemburg’s skull with a rifle butt, then shot her and threw her into the Landwehr Canal. (Her body was found and identified four months later.) Liebknecht was shot in the back and his corpse taken to the morgue.***** The official account of their deaths said that Liebknecht had been shot while trying to escape capture and that Rosenburg had been killed by an angry mob. The Freicorps unit commander later admitted, with some pride, that he ordered them executed.

The defeat of the Separatist revolt saved the republic in the short run, but in fact that defeat held within it the seeds of the republic’s death fourteen years later.

*After the Roman gladiator Spartacus, who led a slave rebellion in Rome in the first century BCE. In retrospect, naming themselves after the leader of a rebellion that failed and ended in the crucifixion of six thousands of its participants was perhaps not such a good idea.

**You met Liebknecht several weeks ago, when he declared the creation of a socialist republic republic from the balcony of the royal palace.

***If you have any doubts about the fact that socialists and communists are not the same thing politically, spend some time reading about the Weimar republic. The two parties disagreed on just about everything–loudly, often, and occasionally with the use of violence.

****Known as the Freikorps, these militias were made up of former soldiers of the imperial German army. They were trained and equipped by right-wing officers of the Weimar army. Despite the fact that they were used in putting down the Spartacist revolt, these units were not citizen soldiers with official standing. They would remain a problematic element of society throughout the Weimar Republic and became stalwart supporters of the Nazi movement.

*****Nothing I’ve read explains, or even asks about, the difference in how their assassins treated the bodies. Personally, I believe it was rooted in the disdain for women that became part of the Nazi ethos. But I am just making this up.