Road Trip Through History: The Sergeant Floyd River Museum

In some ways, the Sergeant Floyd River Museum in Sioux City, Iowa, feels like the historical equivalent of a set of nesting Russian dolls, with one iteration of Sergeant Floyd fitted into another and then another to make up the whole.

- The historical heart of the museum is Sergeant Charles Floyd himself. He was a member of the Lewis and Clark expedition who died of what was probably a ruptured appendix on the site of modern Sioux City Iowa, the only member of the expedition to die on the journey. A granite obelisk marking his grave stands on the high ground over the city, the first nationally registered historical landmark in the United States.*

- The museum is housed in the M.V. Sergeant Floyd, named after Charles Floyd. The boat was used by the United States Corps of Engineers for light towing, survey and inspection work, and improvement projects on the Missouri River from 1932 to 1975 as part of its mission to keep “Old Misery” navigable. Beginning in 1976, as part of the nation’s Bicentennial celebration, the Corps used the boat as a floating museum.

- In 1983, Sioux City bought the decommissioned vessel and turned it into the Sergeant Floyd River Museum, which devotes a fair amount of space to the story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with an emphasis on, ahem, Sergeant Charles Floyd. (Including a reconstruction of his face by a forensic artist, using a plaster cast of his remains from the fourth time that he was reburied. In one of those quirky coincidences that pop up in history-land now and then, the artist turned out to be a great-grandniece of Sergeant Floyd.)

The museum is fundamentally a local history museum housed in an unusual facility. After the section on Lewis and Clark, the museum moved on to a brief and not very sophisticated exhibit about the Native American peoples who inhabited the area before white settlers arrived.** From there it went on to look at the fur trade, the founding and development of Sioux City as a depot on the Missouri River, and steamboat traffic on the Missouri. (These weren’t the steamboats of your imagination. The steamboats that traveled the Missouri were intercity trade boats, not the gilded palaces that traveled the Mississippi from St. Louis to New Orleans.)

The parts that captured my imagination the most were the panels dealing with navigation on the Missouri River, beginning with the Lewis and Clark expedition. Before the Corps of Engineers took over the task of trying to keep the river navigable in the mid-19th century, piloting a boat down the river required skill and luck. The river was nicknamed “Old Misery” for a reason. Its channels shifted on a regular basis, thanks to summer storms, winter ice dams, and the annual rise of the river’s water level each spring. The upper reaches of the river were clogged with snags and sandbars, some of which could not be steered around, slid over, or smashed through. Snags that broke away from the bottom during high water could collect in log jams, which the French-Canadian rivermen called embarrases—”hinderances.” These could pin a boat broadside and cause it to capsize—a situation that could be described by another meaning of embarras, a predicament.

All these hindrances, and the possible predicaments caused by them, inspired rivermen to develop a number of ways to get around them, including:

- The Lewis and Clark expedition, and every keelboat captain who followed them, used a technique known as cordelling, in which rivermen walked their boats upstream when the river was too clogged by snags or the current was too strong for rowing, pulling it with a heavy line attached to the boat. Sometimes they walked along the bank, sometimes they worked waist deep in the river. The line itself was known as a cordelle, from the French word for rope, a holdover from the days when French voyageurs controlled the Missouri and Mississippi. Which were not that long ago from the perspective of Lewis and Clark.

- When conditions didn’t allow cordelling, rivermen harnessed the strength of the trees that lined the river (and were responsible for the snags) in a related technique called warping, in which they tied the cordelle to a tree and then hauled the boat hand over hand up the river

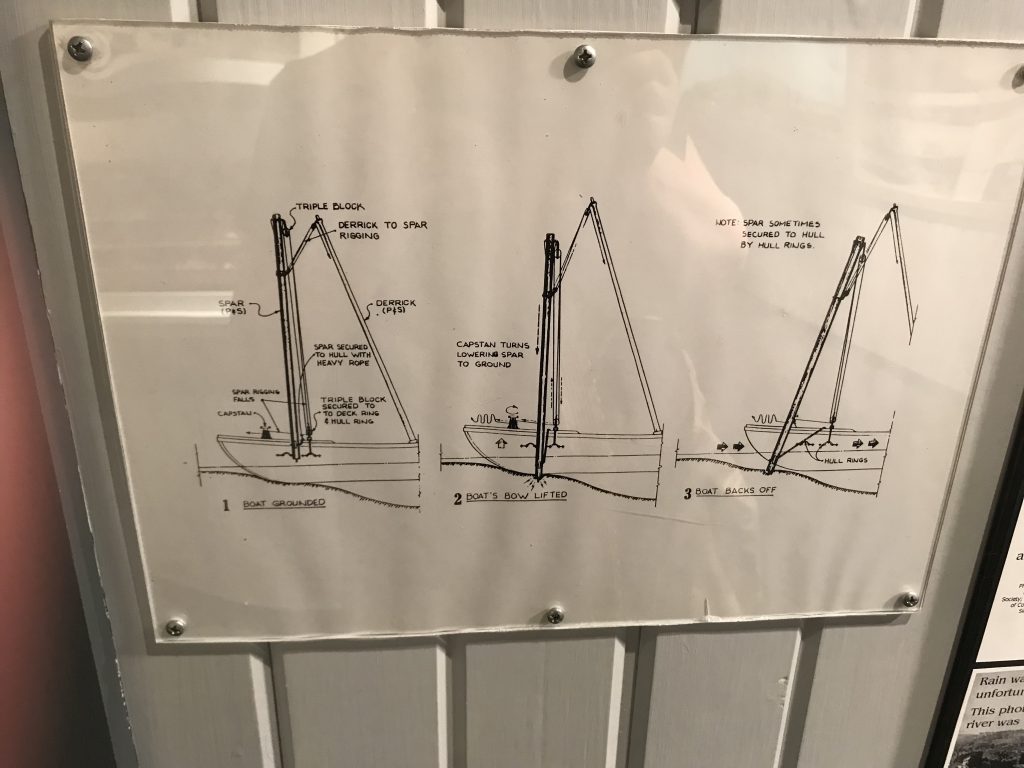

- By the days of steamboats,*** every Missouri River steamboat carried a pair of “grasshoppers”: tall wooden poles that could be lowered into the mud and used like giant crutches (or possibly chopsticks) to “walk” the boat to deeper water.

Human ingenuity never ceases to amaze me.

* If we had known this at the time, we might have made the time to drive up the hill to see it. Or maybe not. We also chose not to stop at the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center, which was located in the same museum campus as the Sergeant Floyd River Museum. Our long road trips are a constant set of compromises between the time, distance, and interest.

** This is a subject that not many local history museums do a good job with, and that some ignore altogether. After visiting many, many such museums over the decades years, I’ve come to the conclusion that local history museums that focus on a specific element of Native American history in their region create more meaningful exhibits than those that make sweeping generalities. In fact, I would argue that is true for small museums as a whole. Give me a specific story that illustrates a topic rather than trying to give me the story of the fur trade as whole.

***Earlier than I realized. Steamboats were introduced on the western rivers in 1811.

Travelers’ Tip: I recommend Madonna Rose in Sioux City for breakfast. The restaurant’s huevos rancheros, served on a base of black bean and chorizo chili was pretty amazing. In fact, it has me plotting how to make a similar chili at home come the fall.

Would love to know the route you follow, even if you post that after the fact.

Happy to share: US Highway 20 from Chicago to Dubuque. From Dubuque, we went north to US 18, which we took across Nebraska. We dropped down to Sioux City, Iowa on US 20, and then drove from Sioux City to Cody, Wyoming, most on US 20. We took the interstate back for reasons of time.