From the Archives: The Crusades from A Different Perspective

In every book I write I reach the point where I am so deep in the work that I have to stop writing blog posts and newsletters. I always hope to avoid it. That somehow I’ll be smarter, or faster, or more organized, or just more. This time I’ve managed to avoid hitting the wall for several months by cutting back to one post a month. But the time has come. For the next little while, I’m going to share blog posts from the past. (This one is from 2014.) I hope you re-discover an old favorite, or read a post that you missed when it first came out.

There will be new posts in March no matter what: we celebrate Women’s History Month hard here on the Margins. (I have some fascinating people lined up.)

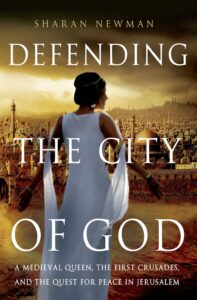

Recently I’ve been reading Sharan Newman’s Defending The City of God: A Medieval Queen, The First Crusade And The Quest for Peace In Jerusalem. It was a perfect read for March, which was Women’s History Month.*

Newman tells the story of a historical figure who was completely new to me. Melisende (1105-1161) was the first hereditary ruler of the Latin State of Jerusalem, one of four small kingdoms founded by members of the First Crusade. Her story is a fascinating one. The daughter of a Frankish Crusader and an Armenian princess, Melisende ruled her kingdom for twenty years despite attempts by first her husband and then her son to shove her aside. Even after her son finally gained the upper hand, Melisende continued to play a critical role in the government of Jerusalem. Those few historians who mention Melisende at all tend to describe her as usurping her son’s throne.** Newman makes a compelling argument for Melisende as both a legitimate and a powerful ruler. (In all fairness, this is the kind of argument I am predisposed to believe.)

Fascinating as Melisende’s story is, Newman really caught my attention with this paragraph:

Most Crusade histories tell of the battle between Muslims and Christians, the conquest of Jerusalem and its eventual loss. The wives of these men are mentioned primarily as chess pieces. The children born to them tend to be regarded as identical to their fathers, with the same outlook and desires. Yet many of the women and most of the children were not Westerners. They had been born in the East. The Crusaders states of Jerusalem, Edessa, Tripoli, and Antioch were the only homes they knew.

Talk about a smack up the side of the historical head!

If you’re interested in medieval history in general, the Crusades in particular, or women rulers, Defending the City of God is worth your time.

* It was also nice to spend some time in a warm dry place, if only in my imagination. Here in Chicago, March came in like a lion and went out like a cold, wet, cranky lion.

** To put this in historical context. Melisende’s English contemporary, the Empress Matilda (1102-1167) was the legitimate heir to Henry I. After Henry’s death, her cousin Stephen of Blois had himself crowned king and plunged England into a nine-year civil war to keep her off the throne. Apparently twelfth century Europeans had a problem with the idea of women rulers.