Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Susan Ware

A pioneer in the field of women’s history and a leading feminist biographer, Susan Ware is the author and editor of numerous books on twentieth-century U.S. history. Educated at Wellesley College and Harvard University, she has taught at New York University and Harvard, where she served as editor of the biographical dictionary Notable American Women: Completing the Twentieth Century (2004). Ware has long been associated with the Schlesinger Library at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute, most recently as the Honorary Women’s Suffrage Centennial Historian. From 2012-2022 she served as the general editor of the American National Biography. She is currently writing a book about feminist biography and preparing two volumes on Eleanor Roosevelt for the Library of America.

Take it away, Susan!

You are one of the second wave feminist historians who helped create women’s history as an academic discipline. What sparked that interest for you? And did you face institutional challenges in addition to all the other challenges that confront someone writing about women in the past?

My interest in history was sparked by growing up as a voracious reader—I always had a book in my hands (still do). My interests vacillated between literature and history but in college I tilted towards history. This was the late 1960s, so it was very much “men’s” history, even at the women’s college I attended. But in 1970 I became aware of the powerful ideas of modern feminism, which caused me to ask “where are the women in history?” I never looked back. One institutional difference between my career and those of other, slightly older second-wave women’s historians is that they often started their careers in another field like Russian history (Linda Gordon), diplomatic history (Blanche Wiesen Cook), or colonial history (Linda Kerber) and then switched to women’s history, whereas I applied to graduate school in 1972 with the stated purpose of studying women. Why Harvard admitted me given their hostility to women’s history then and for many years after (talk about a chilly academic climate!) has always been a puzzle, but I thrived once I discovered the resources of the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe and found mentors like Barbara Miller Solomon. Fifty years later I’m still at it.

You’ve written about a lot of interesting women. Do you have a favorite?

When Martha Graham was asked her favorite role, she would reply “the one I am dancing now.” Babe Didrikson Zaharias said the same thing about sports. I have always felt that way about my subjects, especially the biographical ones: my favorite is the one I am writing about now. But if I had to choose, it would be Amelia Earhart. I published Still Missing: Amelia Earhart and the Search for Modern Feminism thirty years ago and yet whenever I am asked to talk about her, I find myself just as excited and engaged as when I was researching the book. This is a good thing, actually, because I still am fielding calls, requests for interviews and lecture invitations on Earhart on a regular basis – and probably will until they find her plane. Such is her enduring hold on popular culture, whose coattails I have been delighted to ride.

For a book like Why They Marched, in which you look at a group of women, how did you chose which women to include?

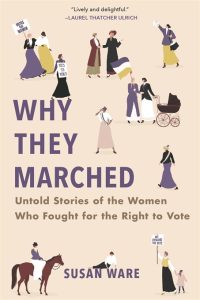

Why They Marched, my recent book on the women’s suffrage movement timed to the centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment, is a collection of nineteen portraits (the actual term is prosopography, but that’s too much of a mouthful) designed to capture the experiences of rank-and-file suffragists who made the vote happen in localities across the country. Biography –telling stories – is a perfect way to make the history come alive. I steered clear of national leaders (although I did include Susan B. Anthony) and tried to chose a range of subjects who represented the broad diversity of the movement in terms of chronology, geography, race, class, sexual identity and age. In addition I wanted to include a male suffragist as well as a female anti-suffragist. It was one huge balancing act but great fun too. Many of the subjects had some connection to the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe, which has been my go-to library since graduate school. In many ways Why They Marched is a love letter thanking the Schlesinger Library for what it has meant to my career.

A question from Susan: During an intense few months in 1970 I was introduced to the powerful ideas of modern feminism by reading Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, and Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. Have you ever had a comparable life-changing feminist experience?

I was thirteen, going on fourteen, in 1972. I had already had the confusing experience of people telling me, on the one hand, that I was smart enough to do anything I wanted and, on the other hand, that there was a whole universe of things I couldn’t do because I was a girl. Then, seemingly all at once, the world changed with the passage of the Civil Rights Act, and Title XI in particular. For a brief, giddy time it seemed like anything was possible. That all the doors were open. I soon learned that wasn’t true: that some doors were still closed, and others were nominally open but had gatekeepers intent on keeping me from coming through them. But I never lost that sense of possibility—and I developed a taste for hip-checking my way through closed doors.

***

Want to know more about Susan Ware and her work? Check out her website at https://www.susanware.net/

***

Tomorrow it will be business as usual here on the Margins with a women’s-history- related blog post from me. But we’ve still got more people talking about women’s history from a lot of different angles next week. Don’t touch that dial!