Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Diana Parsell

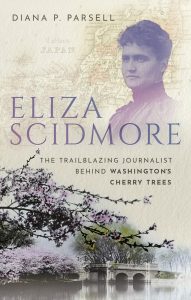

Diana Parsell is a writer, editor, and former journalist in the Washington, D.C., area. She has worked for publications and websites including National Geographic and The Washington Post, and for science organizations in Washington and Southeast Asia. A graduate of the University of Missouri School of Journalism and Johns Hopkins University’s M.A. program in nonfiction writing, Parsell was one of the founding editors of the online Washington Independent Review of Books. In support of her debut book, Eliza Scidmore: The Trailblazing Journalist Behind Washington’s Cherry Trees (March 2023, Oxford University Press), she received a

What was the most surprising thing you found doing historical research for your work?

Given the meager knowledge of my subject, the 19th-century author and travel writer Eliza Scidmore, it surprised me greatly to eventually uncover so much unknown information about her. Today, people know her mainly as the woman who fought a century ago to have Japanese cherry trees planted in Washington, D.C. But personal details about her have always been sketchy. There had never been a biography of her, and I learned early on that most of her personal papers were destroyed after her death. Because of this, I had little to go on when I started looking into her life. I didn’t know whether I would even find enough for a book. Because I’m not trained as a historian or scholar, I began with little understanding of standard techniques for doing historical research. I simply followed one clue after another. Over several years, this led me to an unexpected wealth of material, much of it buried in archives and “hiding in plain sight” in public records and databases. Digitization and other advances in research tools enabled me to uncover valuable primary sources that had long been overlooked.

Major breakthroughs occurred along the way. As one example, I was a couple years into the research when I discovered that Scidmore wrote her newspaper work under a pen name. That opened the floodgates to hundreds of articles she published. This body of work, never previously examined in full, proved enormously important. For one thing, it showed that Scidmore deserves greater recognition as one of America’s pioneering female journalists—a contemporary of the early newspaperwomen historian Alice Fahs describes in Out on Assignment (University of North Carolina Press, 2011). The newspaper datelines provided a core chronology of Scidmore’s life and early travels. And of course, the columns gave me her own words, as well as insight into her character and personality.

Another major surprise was discovering the significance of Scidmore’s reporting on China. In a couple of monographs that turned up, two different scholars described her as one of a handful of Western writer-travelers who “opened” China to mass tourism at the end of the nineteenth century. Even though I knew she published a book on China, this perspective offered a whole new dimension. In the end, I found so much material relevant to her travels in China that had I not been limited by a tight word count, I could have written a lot more about this important and little-known aspect of her life.

Writing about a historical figure like Eliza Scidmore requires living with her over a period of years. What was it like to have her as a constant companion?

I came to my research on Scidmore motivated by many questions. Among them, I hoped to find out what inspired her obsessive efforts to have Japanese cherry trees planted in Washington’s newly developed Potomac Park a century ago. More personally, it was questions about her personal life that intrigued me. I had read in general about her accomplishments: pioneering traveler to Alaska and author of the first tourist guide on the region; first woman elected to the board of the National Geographic Society (in 1892); activist in the burgeoning U.S. conservation movement, in affiliation with John Muir and others; recognized expert on Japan and author of a half-dozen travel books. I couldn’t help but wonder how she managed to achieve so much, at a time when few women had careers and society frowned on female ambition. I came to realize that Scidmore was still in her twenties when she first pitched her idea for cherry trees in Washington to the men in charge of the city’s public parks. What would have given a young woman of that era the confidence and audacity to make such a bold move. Who was she and where did she come from? What influences led her to act as she did, not just on D.C.’s cherry trees but in her larger life?

These, then, were the kinds of questions that ultimately drove my research. Searching for the answers made her not just an inviting companion in the decade it took me to write this book, but a subject in whom I hoped to better understand what it takes for women to succeed in a male-dominated world. She became a compelling figure because of questions I had about her that resonated with my own experience and that of other women I knew. Questions of how to make a life when one’s instincts don’t accord with family or societal expectations; how to reconcile a hunger for freedom and creative expression with the need to make a living; how to stay true to one’s values in a society that values conformity.

In writing the first-ever biography of Scidmore, I tried to make the writing accessible to general audiences, to spread her story as widely as possible. But I was also quite conscientious about documenting my sources thoroughly as a “blueprint” for further studies and analysis of her life and career. I feel sure she’ll continue to be in my life for some time, and I can’t wait to learn even more about her.

What work(s) of women’s history have you read lately that you loved?

One book that comes immediately to mind is Carolyn Fraser’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Prairie Fires: The American Dreams of Laura Ingalls Wilder. I found it impressive for the marriage of biographical insights and Fraser’s geographical rendering of the American plains as the backdrop of pioneer life. I’m a big proponent of master biographer Robert Caro’s conviction that place and setting play a crucial role in shaping a subject’s feelings, drives, motivations and insecurities. Fraser addressed this masterfully. I also loved A Woman of No Importance, by Sonia Purnell, and All the Frequent Troubles of Our Days by Rebecca Donner. Both of these elevate biography to a higher order in using the dramatic techniques of storytelling to illuminate critically important historical events.

As far as a top recent favorite of women’s history, however, my hands-down choice is Gillian Gill’s Virginia Woolf and the Women Who Shaped Her World. Like many women with strong literary leanings, I’ve read a lot of Woolf’s work. I’ve also read biographies about her. But nothing I’d read before matched the level of insight and analysis I got from Gill’s book. Focusing on Woolf’s heritage, she describes various women in the family who greatly affected Woolf’s growth and development–as both an unconventional woman of her day and a radical writer. Reading this book made me want to go back and reread all of Woolf’s work!

A question from Diana: Given how far history has lagged in giving us the important stories of women, as well as other marginalized groups, do you have any ideas for strategies on how to move the narrative forward in leaps, instead of through individual efforts and incremental progress?

I wish I did. Unfortunately, I suspect the only way this happens is one story at a time, until the narrative reaches the point at which “women’s history” is accepted as mainstream history. (I picture this as a narrative rockslide, where erosion occurs over time and then BAM! it happens. Though, of course, this would be positive and non-destructive.*)

*Am I getting loopy as I approach the deadline on this book? Why yes, yes I am.

***

Want to know more about Diana Parsell and her work?

Check out her website: www.dianaparsell.com

Follow her on Twitter: @DianaParsell

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with historian Melissa Blair.