Talking About Women’s History: A Bunch of Questions and an Answer with Dr. Emma Southon

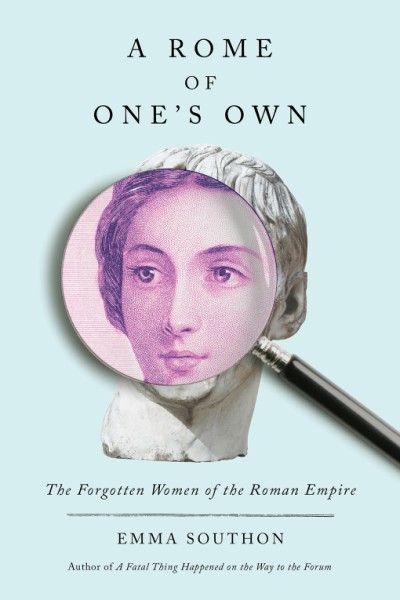

Back in November at least half a dozen of my friends sent me the link to an essay by Emma Southon, titled “Why We Need a Women’s History of the Roman Empire.” I read it and was hooked by the voice and the ideas. I immediately ordered her delightfully titled book, A Rome of One’s Own and invited her to join us here for what turned out to be a whole bunch of questions and an answer.

Dr. Emma Southon holds a PhD in ancient history from the University of Birmingham. The author of A Fatal Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Marriage, Sex and Death: The Family and the Fall of the Roman West and Agrippina, she co-hosts a history podcast with writer Janina Matthewson called History Is Sexy and works as a bookseller at Waterstones Belfast.

Take it away, Emma.

What inspired you to write A Rome of One’s Own? How does looking at classical Rome through the lens of women’s lives change the story?

Mostly I wanted to add to the conversation about ancient women that had started to happen in fiction; after Madeleine Miller’s Circe, this wave of novels about Greek goddesses came out, retelling their stories to centre female narratives. I work in a bookstore and I saw them come in and the little contrary Romanist in me wanted to remind readers that Romans exist (and are, imo, cooler!) And even better, Roman women are real!

When I started compiling lists of women to include in the books and thinking about how to do it, I decided to tell the story of the rise and fall of the empire through women’s stories and lives and found that it mostly removes all the traditional narratives. There’s hardly any battles, no senatorial speeches. It think it makes the Roman empire more real and more clearly a thing that happened to people. The masculine narrative of war and expansion and more war always comes from the perspective of the Romans themselves and it feels so high minded. The female perspective means you have the space to include more stories of people experiencing the Roman empire changing their lives.

In A Rome of One’s Own, you look well beyond the stories of empresses and elite women to talk about slaves, business women, professional women, and women from distant parts of the empire. How difficult is to find sources for women whose lives are not well documented in traditional sources?

The real challenge is finding significant evidence for women beyond a couple of sentences! When I started making lists of potential women, they got overwhelmingly long because there are hundreds of stories that I could include. The problem was that so many of them are documented in just a line or an epitaph and nothing else is known about them. We know one thing about their life, such as that they were married to the commander of an auxiliary cohort that was stationed in Britain for a while in 100 CE, or that they owned a complex of buildings in Pompeii but nothing else. But that’s true for most men too. Most of the traditional literary sources are interested in a tiny minority of men at the tippiest top of the Roman tree and their experiences don’t really reflect the millions of other men who lived in the empire.

You look at a wide range of Roman women. How did you decide which women to include?

With great difficulty! I went through a lot of different lineups. It was dictated in the end by chronology. I knew I wanted women from every phase of Rome’s history until the abdication of Romulus Augustulus and I didn’t want there to be lots of chapters clustered around certain periods (*cough* the julio-claudians *cough*). So I lost a lot of great stories because they just happened to be too close in time to another woman that I included. I would have to make a decision between two or three women and I usually told the story that I thought had been told less, or was less Imperial. For example, Calvia Crispinilla was one that I had in until quite late because she just has a fun Roman story of excess. She’s an African woman who becomes prominent in Nero’s court, and he made her a “mistress of the wardrobe” to his enslaved “husband” Sporus. When Nero was overthrown, she cut off the food supply to Rome in order to try and force the Senate to choose her pick for emperor. Despite all this, she went on to marry a consul, run a wildly successful wine and olive oil business and live rich and happy. It’s a great story! But it’s too familiar, and overlapped with Boudicca and Cartimandua, which I decided were stories that were more surprising and gave a wider view of what living in or with the Roman empire was actually like.

Was there a woman you were sad to leave out?

I was devastated to cut out Babatha, a Jewish woman who lived in the Roman province of Arabia, on the modern border between Jordan and Israel. She died 132 CE because she fled the Bar Kokba rebellion in Judea and holed up in a cave near En-Gedi with various other friends and family to escape the fighting. Unfortunately, none of them ever left that cave but she obviously assumed she would because she took with her a bag full of documents detailing her marriages, her husbands’ other wives, her property disputes, her fights with the Roman governor about a pension for her son, the fist fights she had with the Roman woman who represented her in court, her fig trees. It’s such a glorious archive of a woman’s life! I chose Julia Balbilla instead because I love her but I do sometimes wish I had included Babatha.

You introduce readers to a lot of fascinating and unexpected women. Do you have a favorite, or two?

I’m a big fan of Julia Balbilla! Which is why she won over Babatha. I love her combination of boastfulness and desperation to be remembered; of being hugely educated and smart and rich and royal and also deeply mediocre at poetry! I also love that she has this triple identity as Greek and Roman and Seleucid; royal and not-royal at the same time and that she makes such a big deal about how SHE is descended from gods too, just like Hadrian! I find her so fascinating.

The other is Julia Felix, who we know about only from the fact that she just happened to be renting out her entertainment complex at the exact time that Vesuvius erupted. She’s running this great business, she’s persuading the authorities to move a road for her, she’s showing her customers themselves as epic artwork and giving them a taste of luxury. She’s great.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format? )

I recently loved Jane Draycott’s book about Cleopatra Selena Cleopatra’s Daughter. Her reconstruction of her life and reign after the death of her parents is entertaining and brilliant. The one I recommend to everyone is The Five by Hallie Rubenhold, which blew my mind. I had no idea so much information about Jack the Ripper’s victims existed and it made me totally reevaluate that whole story. One that I love and plunder regularly is Emily Hemelrijk’s Women and society in the Roman world: A Sourcebook of Inscriptions from the Roman West. A collection of women’s lives in epigraphy and graffiti, it contains so many tiny stories.

[Note from Pamela: Look for three questions and an answer with Jane Draycott later this month.]

What do you find most challenging or most exciting about researching historical women?

Challenging is the lack of their actual words. When you get to read the letters of Pliny the Younger or Cicero or Fronto, you get such a thrilling insight into their minds and personalities that we never have for women and it’s infuriating to know they all wrote letters and they were all lost. On the other hand, the lack of big texts means that there are hundreds of fragmentary female stories to be discovered and it is thrilling every time you find a new one. The first time I read Claudia Severa’s letter from Vindolanda it was AMAZING. And when I first read the female-authored sapphic graffiti in Pompeii, I wanted to tell everyone I knew about it. You don’t often get that excitement with a Cicero letter!

You also co-host a history podcast, History is Sexy, which Radio Times describes as “amiably daft.” How would you describe the purpose of the podcast? What types of stories do you discuss?

History is Sexy aims to answer questions that listeners have that they don’t have time to research themselves, in a kind of friendly chatty way. So we are guided by our listeners! Sometimes we do big topics like the history of red heads, or or how men’s clothing got boring or whether matriarchal societies were real (and what a matriarchal society even is). We just did a big two-parter running through the whole Ptolemaic dynasty and then did one on debutante ball culture in the UK and US. It’s always different and usually fun!

You’ve successfully made the jump that many academics dream of, from writing purely academic work to writing books of rock-solid scholarship with a popular audience in mind. Do you have any advice for readers who dream of doing the same?

The main advice I give academics who want to write for non-academic audiences is to stop being defensive in your writing. When you are writing for academics, you know that the first three readers are going to read it looking for holes and everyone else is going to try and mine it for their work/disagree with it. So you become defensive and try to cover every angle. When you’re writing for non-academics, you get to assume that the person reading it already wants to agree with you and learn from you, and they want to be entertained or moved or made to go wow or to learn something cool they can tell their friends. I was lucky that I taught academic writing and writing across the genres for a few years which taught me to break down writing for different audiences but it is hard work to shift from everything you know about writing your subject. Assume you are writing for a friend rather than an enemy!

A question from Emma: Do you think Women’s History Month is important and why?

The answer I come back to every year is that I think it’s important, I love celebrating it, and I wish we didn’t need it.

If you look back at Lori Davis’s mini-interview yesterday, you’ll read a story about a professor who squeezed in an obligatory, uninspired, and unsatisfactory moment of women’s history at the end of each unit in a History of Civilization course. Until we reach the point that women are included in history classes, historical museum exhibits, and living history programs as a matter of course we need Women’s History Month.

In the meantime, I will continue to enjoy the annual carnival feeling of celebrating historical women, well-known and otherwise, with my people across the Internet and in real life

***

Want to know more about Emma Southon and her work?

Visit her website: https://www.emmasouthon.com/

Listen to her podcast: https://historyissexy.com/

***

Come back tomorrow for three questions and an answer with novelist Kip Wilson.