Talking About Women’s History: Three Questions and an Answer with Carolyn Whitzman

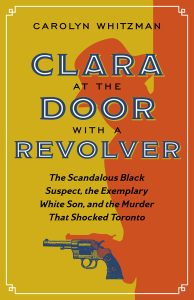

Carolyn Whitzman is a writer and housing policy researcher who lives in Ottawa, Canada. She is the author of Clara at the Door with a Revolver: the scandalous Black suspect, the exemplary white son, and the murder that shocked Toronto (UBC/ On Point Press, 2023) a riveting true-crime story centered on a courageous Black woman living in nineteenth-century Toronto who was charged with murdering the son of a well-do white family and the trial that followed. Her forthcoming book is Home Truths: Fixing Canada’s Housing Crisis (UBC/ On Point Press, September 2024).

Take it away, Carolyn!

What path led you to Clara Ford’s story? Why do you think it is important to tell her story today?

I first came across Clara Ford’s story while working on my PhD over 25 years ago, whose topic was the relationship between stereotypes, social conditions, and housing policies in Toronto’s inner city Parkdale neighbourhood over two centuries. One of the lies told about Parkdale when it was gentrifying in the late 20th century was that it had been a stable, middle-class, residential suburb when it was developed in the late 19th century. But all you needed to do was walk around the neighbourhood and look at old industrial buildings and tiny workers’ cottages to get a sense of social mix – and potential tensions between residents.

I turned to newspapers of the time and quickly came across the story of an impoverished mixed-race tailor, Clara Ford, who was accused of having murdered her former next-door neighbour, the son of a wealthy white manufacturer, in 1894. The more I read about the trial, the more I became obsessed with Clara. Clara was the first person I have found to be described as a “homosexual” in a North American newspaper. Her adventures as a cross-dressing traveller (who passed as a man but not as a white person) contributed to newspaper coverage that made her out as a ‘monster’, even as other newspapers painted her as a ‘tragic mulatto girl’ seduced by a boy almost half her age. Clara was also the first woman and second person in Canada to testify on her own behalf in a trial. She told a story of police harassment into a false confession, which was, remarkably, believed by a jury of twelve white men.

The themes of the book – working class Black life in Canada, sexual violence, police harassment, fake news – continue to be timely today, in a world of #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo. I hope that Clara, like many women of her time and class only written about when she got into trouble, emerges from the book as a strong, brave, and very funny heroine of her own story.

What type of sources do you rely on in writing about a non-elite woman from the past?

What a good wonky question! I used two sets of primary sources and one set of secondary sources.

First off, I used newspaper articles. There were seven daily newspapers in Toronto at the time of Clara’s arrest and trial. They were engaged in a furious circulation war and cared very little about verified truth – the most important thing was a ‘scoop’. I see certain similarities with 24-hour news cycles and social media today.

My second set of sources was official documents of the time – census, directory, assessment, birth and death records… but Clara is remarkably absent from the official record. She only appears in the Canadian census once, as a 7-year-old in 1871 (although she was almost certainly close to 10 years old). There is no birth certificate for her or for her daughters, even though they were, again, almost certainly born in Canada. But I was able to track her white mother, Jessie McKay, through a set of falling down shacks and professions such as laundress and housecleaner.

The third set of sources are some excellent recent works on Canadian women’s history, Black history, legal history, and queer history that helped me put Clara’s story in context. Just about every trope that is still out there, particularly Angry Black Woman, was thrown at Clara. I kept on falling into rabbit holes. For instance, when Clara was acquitted, she joined a famous Black vaudeville troupe as a dancer (at the age of 33!). So I had to know more about late 19th century theatre and the development of the musical. My reference list is quite varied, because Clara lived a rich and complex life in several cities, always trying to stay under the radar.

What work of women’s history have you read lately that you loved? (Or for that matter, what work of women’s history have you loved in any format? )

There are a couple of women’s history books that have rocked my socks in recent years. One is Beautiful Lives, Wayward Experiments: Intimate Stories of Social Upheaval by Saidiya Hartman (Penguin, 2019). Like Clara, Hartman focuses on the lives of 19th century Black women in Philadelphia whose histories are only recorded because they encountered police and other authorities. Hartman writes about vibrant but forgotten women with a poetic sensibility that creates ravishing prose.

Square Haunting: Five writers in London between the wars, by Francesca Wade (Random House, 2021) focuses on a single street in the Bloomsbury neighbourhood, where relatively privileged and educated women in the early 20th century were trying to create new lives as independent writers. Wade’s sense of place, detail, and character lingers in my mind.

I also want to shout out to my favourite podcast, What’s Her Name, created by sister historians Katie Nelson and Olivia Meikle. They are gifted storytellers and I always enjoy travelling with them to re-discover cool women who have been forgotten!

[Pamela butting in here: I, too, am a big fan of the What’s Her Name podcast and the women who created it. In fact, they’ve participated in Three Questions and an Answer several times. You can find their Q & As here, here, and here ]

A question from Carolyn: Can you tell me something surprising you have found about South Asian women’s history, please?

My most recent surprises from South Asian women’s history have not been large scale cultural issues, but stories about individual women who did not show up in my graduate student course work. One of my favorites of these is Raziya Sultan (1205-1240 CE), who was the only female ruler of the Delhi Sultanate in India—a Muslim empire that ruled over a large portion of India for several centuries prior to the Mughals.

Although she had several brothers, her father named her his successor to the throne. It probably will not surprise you to learn that neither her brothers nor the Muslim nobles in the sultanate were pleased with his choice. At his death in April, 1236, they attempted to put one of her brothers on the throne. He was described in the chronicles as being “incompetent”—which could mean many things. His mother was in control of the throne during his brief reign, which ended six months later when mother and son were assassinated.

Raziya then ascended to the throne. (It is unclear to me if she was involved in the assassination, but I would not be surprised if that were the case, family politics in medieval kingdoms, Muslim and otherwise, being what they were.) She was by all accounts an effective ruler, but the Turkish nobility, led by one of her brothers, rose up against her. She was defeated in 1240 and died soon thereafter, though accounts of her death vary.

A contemporary chronicler summed up her career with words that could be applied to that of many women who attempted to hold a throne at the time: “She was endowed with all the qualities befitting a king, but she was not born of the right sex, and so in the estimation of men all these virtues were useless.”

***

Want to know more about Carolyn Whitzman and her work?

Check out her Google scholar profile:

Follower her on the platform previously known as Twitter: @CWhitzman

***

Tomorrow it will be business as usual here on the Margins with a blog post from me. Then we’ll be back on Monday with an interview with Sarah Percy, author of Forgotten Warriors: The Long History of Women in Combat, a subject dear to my heart.