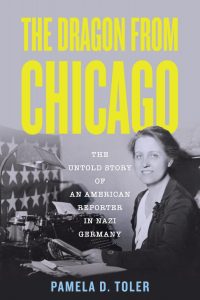

It’s Publication Day for The Dragon From Chicago!

On May 8, 2020, I announced here on the Margins, after months of hinting, that I had a contract with Beacon Press for a new book about Sigrid Schultz, Berlin bureau chief for the Chicago Tribune. I expected to finish the book in two years. *Cue manic laughter*

Four years and a bit later, The Dragon from Chicago is finally out in the world.*

I’ve spent the last four years deep in the world of foreign correspondents, American newspapers. Weimar Germany, “false news,” glass ceilings, American isolationism, Nazis, the Lost Generation, the rise of radio news, daily life in Berlin, and the challenges of getting the news out in the face of tightening controls over the press. I’ve learned a lot in the process, and I’ve tried to share it with you every step of the way, from big stories like the rise of the Weimar Republic to small ones, like my realization that Oscar Mayer, of wiener fame, was a real human being.

Thanks for your support and encouragement along the way. It kept me going on the days when I wasn’t sure anyone would care.

You’ve already received the information that I’m throwing an on-line launch celebration tonight**, in conversation of Olivia Meikle, co-host of the What’s Her Name Podcast. If you’ve already signed-up, you’ll get the Zoom link today. (It may already be in your in-box.) If you didn’t sign up and wish you had, here’s the link:

Join Zoom Meeting

https://us06web.zoom.us/j/87516374458?pwd=UGaOsk76MUIm5PcMF8JtuBN4muZgsa.1

Meeting ID: 875 1637 4458

Passcode: Party

Starting Friday, we’ll be back to business as usual here on the Margins, with some stories that didn’t make it into the book, some Road Trip Through History adventures, and reviews of books that I hope you’ll enjoy as much as I have. There’s never a lack of history to share!

*If you literally see it out in the world, take a picture and share it with me! Or better yet, share it in your social media feeds.

**Assuming you’re reading this on August 6

One Final Woman War Correspondent: Helen Kirkpatrick

American reporter Helen Kirkpatrick (1909-1997) had already spend five years as a foreign correspondent in Europe when America entered World War II.

She had stumbled into reporting in1 935. After a summer job escorting 30 teenage girls around Europe, she cabled her husband that she wasn’t coming back and found a job with the Foreign Policy Association in Geneva. The FPA was located near the press room in the League of Nation’s building. She not only made friends with reporters, she began covering for them when needed. After a time, the European office of the New York Herald Tribune offer her a job as a stringer with a regular, though very small, salary. She jumped at it.

In 1937, she moved to London, where she worked as a freelance contributor for a number of newspapers. During the Munich Crisis, she was a temporary diplomatic correspondent for the Sunday Times.

During her time in London, she published a weekly newsletter, along with Victor Gordon-Lennox of the Daily Telegraph and Graham Hutton of the Economist. Titled Whitehall News, it campaigned against the British government’s policy of appeasing dictators: Winston Churchill, Anthony Eden, and the King of Sweden were all subscribers. (I assume Neville “Peace in our time” Chamberlain was not.)

Shortly before the war she joined the London office of the Chicago Daily News, the owner of which had previously refused to hire women staff writers. Her first assignment was to get an interview with the Duke of Windsor, who was well known not to give interviews.* Despite the scoffing of her male colleagues, she was able to get a meeting with the former king. He reiterated that he did not give interviews, but saw no reason that he couldn’t interview her. That reverse interview was her first by-lined story in the paper

Kirkpatrick worked for the Chicago Daily News throughout the war. She wrote about the London Blitz, covered the arrival of the first troops of the American Expeditionary Force in Ireland, and spent six months reporting on the North African campaign in 1943, including the surrender of the Italian fleet at Malta. After D-Day, she became the first correspondent assigned to the Free French headquarters in Europe. She entered Paris on August 25 1944 riding in a tank with General Leclerc’s 2nd armored division. Her final wartime assignment was a trip to Hitler’s mountain retreat at Berchtesgaden—almost a required stop for American correspondents at the end of the war.

She was the only woman correspondent who received medals of valor from both the United States and the French governments for her war coverage.

She continued to work as a foreign correspondent for a few years after the war—working for the New York Post, which had taken over the Chicago Daily News. She then moved into the public sector, first as an information officer for the Marshall Plan office in Paris and then as the Public Affairs Office for the Western European Division of the State Department.

She gave up her career when she married Robbins Milbank in 1954. Not an unusual decision at the time, though a loss to journalism.

*This sounds to me like someone was setting her up to fail.

***

One short week until The Dragon From Chicago hits bookstore shelves. Am I excited? Darn tootin' I'm excited!

Heads up to my Chicago people: The event on August 6 at City Lit Books has been cancelled.

Ann Stringer: The Widow on the War Front

Ann Stringer (1918-1990) was a reporter for the United Press before the beginning of World War II. She had reported alongside her husband, Bill Stringer, from Dallas, Columbus, and New York and as foreign correspondents in Latin America. By 1944, both of them were eager to be reassigned to Europe, where the real action was. They struck a deal with Reuters. Not surprisingly, Bill got his accreditation as a war correspondent first.* The plan was that Ann would follow as soon as her accreditation came through.

The day Ann was scheduled to leave for Europe, she learned that Bill had died in Normandy.

She was even more determined to get to the war front and cover the big stories. She sailed for England in late 1944 as an accredited war correspondent with the United Press. She filed her first story from London in January, 1945, then moved to the First Army press camp, where Bill had been assigned. According to Andy Rooney,** when Ann replaced Bill Stringer on the job “the rest of us in the First Army press camp didn’t know how to act toward her. Ann made it easy. She just picked up and did Bill s job, often with tears in her eyes."

As is so often the case when a widow steps into her husband’s field boots, Ann exceeded expectations. And her colleagues at the United Press did not hesitation to admit it. According to Walter Cronkite, "She was tough. She knew what she wanted, and she knew how to get it. And she was one of the best reporters I have ever known. And, yes, she was beautiful." Harrison Salisbury took his praise even further: "What I can tell you about her is that she was simply superb, the best man (I’ll say that even if it sounds chauvinistic) on the staff. Annie illuminated every one of her assignments. She was all reporter--not ‘girl reporter’—straight reporter. She was a two-fisted competitor."

Stringer often ignored the Army’s restrictions on women in the front and was warned at least once that refusal to comply would lead to the loss of her accreditation. She learned to file her stories with vague datelines that wouldn't trigger questions at army headquarters. When she couldn’t get official jeep transportation to the combat zone, she begged unofficial rides, including a lift over the bridge at Remagen from a general in a tank.

She is best known for sending the first dispatch reporting the link-up between the American and Soviet armies at Torgau, Germany, on the Elbe River, on April 26. She persuaded a friend in Army Intelligence to lend her and an INS photographer two small spotter planes and the pilots to fly them to Torgau. After an hour in Torgau, carrying her typewriter and a roll of film, she hitched a ride to Paris on a C-47 cargo plane and scooped her competitors/colleagues.***

Ann continued to report from Europe through the summer of 1945 and later covered the Nuremberg trials. In 1949, she left United Press, married German-born American photographer Hank Ries, and settled in Manhattan, where she continued to write for a variety of news media.

*Even before 1944, when the United States put regulations in place distinguishing between male and female correspondents, there were always limitations on women, even if they were “written in invisible ink” as photojournalist Margaret Bourke-White put it.

**Yes, that Andy Rooney. Even crotchety old icons were once bright-eyed young reporters. (Or maybe he was a crotchety young reporter. I don’t know for sure.)

***Other correspondents were always both.

***

Twelve days until the publication of The Dragon From Chicago! So. Dang. Excited.