Betty Wason and the “Problem” of the Female Voice

As I have mentioned before, American radio executives were not enthusiastic about hiring women to broadcast hard news. They believed that American listeners were perfectly happy to hear women read ads on the air, talk about about recipes and housework, or even, interview guests. But despite the success of radio personalities like Mary Margaret McBride, and to a lesser extent, *ahem*, Sigrid Schultz, radio executives were sure the American public did not want to hear a female voice delivering the news.

The most egregious example of this is the case of Betty Wason (1912-2001). She had tried unsuccessfully to get work with CBS before World War II began. Then Germany invaded Norway on April 9, 1940 Wason was in Sweden at the time and received a call from the CBS representative in Berlin. The network needed someone to broadcast from Scandinavia NOW. She found a woman who could translate breaking news from the Swedish papers for her first broadcast, which allowed her to scoop the other networks. She followed the first broadcast with more war news from deep in Norway. In May she got a call from CBS asking her to find a man to broadcast in her place because her voice was too young and feminine for war news. She reached out to a male reporter, coached him through his first broadcast, taught him how to write for radio, and lost her job to him. (Grrr.)

The story doesn’t end there. Wason traveled to the Balkans, which had become a hot spot. Her replacement followed her. She filed a few print stories from Turkey. Then she went to Athens, where she reported for CBS again, and was again asked to hire a male broadcaster. This time she hired a young secretary from the American embassy in Athens to be her voice. Unlike his predecessor, he had no interest in replacing her, in fact, he introduced himself as “Phil Brown# speaking for Betty Wason.” She continued to run the CBS bureau in Athens until the Nazis occupied the city in April 1941. The Germans held Wason and several other American reporters for almost two months. They were finally allowed to leave when German correspondents were ordered to leave the United States. They flew from Athens to Vienna, where they were detained as suspected spies, and then transported to Berlin by train under Gestapo guard.

Wason returned to the United States, where the Newspaper Women’s Club honored her “for the daring and courage she had shown in her war coverage in Norway, Finland, Greece and elsewhere. Despite their recognition, she was not able to get broadcasting work with CBS. She turned to print journalism and wrote a book about her experience in Greece, titled Miracle in Hellas (1943). After the war, she built a successful career, publishing another 23 books, many of them cookbooks, and working as an editor for women’s magazines. She also found work in radio, as a talk show host rather than a broadcast journalist.

#Not his real name

***

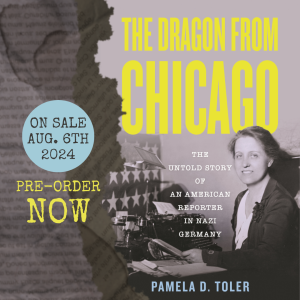

Two weeks and counting until The Dragon from Chicago releases. In case anyone wants to know.

Clare Hollingworth: The scoop heard round the world

Clare Hollingworth (1911-2001) was one of the most active war correspondents of the 20th century. No, really.

She began her career with a bang.

In March, 1939, after German annexed the German-speaking part of Czechoslovakia known as the Sudetenland following the Munich Agreement, Hollingworth began working for the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia. Stationed in Katowice in southwestern Poland, he job was to arrange visas for and evacuation of the Czech refugees who were pouring into Poland. She was so efficient that she was fired in July for overturning standard procedures for vetting refugees, apparently because she was admitting too many people that British intelligence felt were politically or ethnically undesirable. (I suspect that meant Jewish.)

A month later she was back in Poland as a war correspondent for the Daily Telegraph, and once again stationed on the Polish-German border in Katowice. Soon after arriving, she borrowed the local consul’s car, which boasted the armor of a diplomatic flag, and drove across the border into Germany, ostensibly to buy aspirin and other goods not available in Poland. She drove back along the border, where a large canvas screen had been erected on the German side that made it impossible to see into the neighboring valley. When a large gust of wind caught the burlap she saw “large numbers of troops, literally hundreds of tanks, armored cars and field guns.” She hurried back to Katowice and filed the story that German troops were massed along the Polish border.

Three days later, on September 1, 1939, she woke at five in the morning to the sound of tanks rolling past her window. She immediately called her editor, as well as the British Foreign Office, to report the beginning of Germany’s invasion of Poland. It took her a few moments to make any of them believe her. (She held the telephone receiver out the window so they could hear the tanks roalling by.)

A week into her new job, Hollingworth had scooped the world, twice. (Both stories ran without her byline.)

She went on to report from Romania, Bulgaria, Greece and Egypt during World War II. (When British General Bernard Law Montgomery banned women reporters from the front lines in Egypt, she wrangled an accreditation from Time magazine and attached herself to the American army.)

In the forty years after World War II, she traveled the world equipped with what she called her TNT kit—a toothbrush and her typewriter. Working first for the Daily Telegraph and later for the Guardian, she reported on international hot spots including the fall of Eastern Europe to communism, the bloody and complex Algerian war from 1954 to 1962, the Vietnam War, and the final years of China’s cultural revolution. She was the first reporter to uncover the defection of Soviet double agent Kim Philby. (Her paper refused to publish the story for almost two months for fear of being sued.) She also wrote five books: Poland’s Three Weeks’ War (1940), There’s a German Right Behind Me (1943), The Arabs and the West (1952), Mao and the Men Against Him (1985) and her memoir, Front Line (1991).

In 1981, she arrived in Hong Kong, planning to stay a few months to finish her biography of Mao Tse Tung. She never left. She continued to write as a stringer for international newspapers and magazines through the 1990s—in 1989, when she was nearly 80, she climbed a lamppost in Tiananmen Square to get a better view of the protestors, and the government protestors. She stopped work only when increasing macular degeneration in her eyes made it impossible for her to continue.

Hollingworth passed away at the age of 105. By some accounts, she still kept her shoes next to the bed and her passport in easy reach in case she needed to leave in a hurry. Old habits die hard.

Toni Frissell: From Fashion Photographer to the Front Line

Toni Frissell (1907-1988) was born into a privileged Manhattan family. She used her background of wealth and social position to build a career as a fashion photographer for Vanity Fair, Vogue and Town and Country. She was one of the first photographers to move fashion photography out of the studio, transforming the way fashion and the fashionable were presented in print.

By the end of the 1930s, as the situation in Europe became more tense, Frissell became anxious to photograph something other than fashion and celebrities, writing "I became so frustrated with fashions that I wanted to prove to myself that I could do a real reporting job." Even with her connections and her track record as a magazine photographer, she was unable to get the type of long-term newspaper or magazine assignment that would allow her to be accredited as a war correspondent.

Since she couldn't get to the front, she used her social connections to pursue wartime assignments with agencies such as the U.S. Office of War Information, the American Red Cross and the Women’s Army Corps. Many of her assignments during this period were photo-reports of society women working for the Red Cross or the federal government—probably not as big a change from fashion photography as she had hoped for. There were exceptions. In 1942, in her role as pictorial historian for the American Red Cross, she covered Eleanor Roosevelt’s Red Cross trip to England and Scotland. One of her most important assignments was a story on Oveta Culp Hobby, the first director of the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAACS). *

It was 1945, when the war was winding down, Frissell got a chance to visit the frontlines as part of a group organized by the Writers’ War Board.** While in Italy, she had the opportunity to photograph the Tuskegee Airman during their daily activities. She was the only professional photographer to photograph the unit, and her work is an invaluable record of their service.

After the war, Frissell returned to fashion photography, including a stint as the first woman staff photographer at Sports Illustrated.

*And later the first secretary of the new Department of Health, Education and Welfare, making her the second woman to hold a cabinet position. So many amazing historical women, so little time to write about them.

**The Writers' War Board was a private organization devoted to producing domestic propaganda during World War II. Establish by mystery novelists Rex Stout at the request of the U.S. Treasury Department soon after the United States entered the war, its original purpose was to organize prominent writers to support the sale of war bonds. It quickly moved beyond its original mission, matching writers with government agencies, and quasi-government agencies, that needed help in shaping their story. Sigrid Schultz, for example, wrote several stories about Nazi Germany for children's magazines at the request of the Writer's War Board. (Not her finest work, I must say.)