Choosing (Historical) Sides

Recently a friend of mine texted me from Culloden in Scotland*--the battlefield where the Duke of Cumberland routed Bonnie Prince Charlie's Jacobite forces and effectively ended the Jacobite cause. (Charles was later involved in a half-hearted French plan to invade England in 1759, but it came to naught.) She wanted to know if I wanted a Jacobite blue bonnet.

- William of Orange (aka William III)

- Bonnie Prince Charlie

My answer--which didn't surprise her--was no. Despite the fact that the exiled Stuarts clearly had the better legal right to the throne, I've always had a soft-spot for that hard-working sober-minded prince, William of Orange. And I've never had much use for Bonnie Prince Charlie--who I've always thought of as a putz rather than a failed romantic hero. (If you have strong opinions on the subject, feel free to yell at me in the comments below.)

Karin's offer of a Jacobite blue bonnet led me to think about the fact that history buffs tend to chose sides. Sometimes it is because we agree with one side's political position. Sometimes it's because we have a family connection to one side of a conflict or a vested interest in the outcome. Sometimes it's simply a question of who won. (Though Lost Causes also have their supporters.***)

And sometimes it simply comes down to preferring one historical figure over another. In my graduate school days, classes on Victorian England quickly divided themselves into two camps on the question of who was the greatest Prime Minister of the nineteenth century, Benjamin Disraeli or William Gladstone. The members of Team Disraeli and Team Gladstone all had good solid arguments supporting their guy, but when you pushed them it eventually came down to a question of personality.****

- Benjamin Disraeli

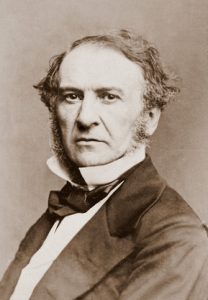

- William Gladstone

Choosing sides isn't necessarily a bad thing, as long as you realize you have a preference. In the end, no one writes objective history.

So tell me, oh Marginalia, what historical sides have you chosen and why?

*Not quite as exciting as the time she called me from Tipu Sultan's palace at Seringapatam.** While I occasionally grumble about feeling like my cell phone is a leash, there is something pretty cool about getting instant communication from far flung historical sites.

**Checking back for an old post to link to, I discover that while I have written about Tipu's Tiger here on the Margins I have not yet written about Tipu. An oversight that will be rectified.

***Which brings us back to Bonnie Prince Charlie. I have to give the man credit for persistence.

****Me? I vote for Robert Peel. Call me contrary.

Word With a Past: Shoddy

In the early nineteenth century British textile manufacturers began to recycle woolen rags into a an inexpensive woolen cloth. The rags were shredded into fibers, mixed with new wood, and then spun and woven into the cloth, which was known as "shoddy"--a term that may have come from an old word meaning divide.* The process was such a success that wool rags for the textile mills were collected all over Britain. For several decades, shipments of rags even arrived from continental Europe.

By the mid-nineteenth century, shoddy was exported to North America in large quantities, where it was available in the American Civil War when the need for Army uniforms put wool cloth from the New England textile mills at a premium. Some clothiers, most notably Brooks Brothers,** used shoddy instead of wool to make uniforms and blankets for the Union Army. (I assume this was war profiteering rather than sabotage.) Some soldiers complained that the uniforms melted to rags in the rain.

As the war went on, profiteering and graft ran rampant. Contractors sold the army tins of spoiled meat, boots with soles made from glued together wood chips*** and unserviceable rifles. The material from which inferior uniforms was made became a description for every piece of second-rate, badly made material that was foisted off on the Army.**** The contractors who made a killing on supplying the war were given the derisive nickname "the shoddy aristocracy."

Shoddy. adj. Made of inferior material .Cheap, inferior, shabby, dilapidated.

*An etymology I offer with hesitation, as does the OED.

**I was shocked.

***Try marching in those.

****Probably with the connivance of a quartermaster or steward on the take. Graft happened at both ends of the supply chain.

From the Archives: Walking Hallowed Ground

When this post goes live, I'll be on my way to Gettysburg for the 2016 Sacred Trust program. Instead of trying to write a new post while my brain is full of Gettysburg, I'd like to share this post from June, 2011, on the question of battlefield visits in general and one special battlefield visit in particular.

Later, y'all.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In response to my recent post on the American Civil War, blog reader Karen Eliot talked about her experiences visiting Gettysburg.

Her comments left me thinking about what makes battlefield visits such a powerful experience. I've certainly walked my share of Civil War battlefields: Gettysburg, Antietam, Pea Ridge, and my hometown battlefield of Wilson's Creek. (Not to mention a few Revolutionary War and War of 1812 sites. I'm an equal opportunity history nerd.) My Own True Love will tell you that I tear up at every battlefield I visit. Or at least get a lump in my throat.

But thinking it over, I'm not sure that the experience would be quite so powerful if the National Park Service weren't there to lead me by the hand. I think it takes a special person to be able to walk into an empty field and see the sweep of a past battle. I'm not that person. I need a guide, an exhibit, or at least a few historical markers. (Have I mentioned how much I love historical markers?)

Which brings me to the battlefield visit that hit me hardest: Gallipoli.

Fought at the Dardanelle Straits, where Turkey has one foot in Europe, the Gallipoli campaign of World War I was the first major amphibious operation in modern warfare. The British and French hoped to drive Turkey out of the war and gain control of the warm water ports of the Black Sea. The campaign started out as a slapdash naval expedition in which the big powers expected to blow Turkey out of the water--so to speak. It turned into the grimmest of trench warfare. Trenches were close enough together that soldiers could toss a live grenade back and forth across the lines several times before it exploded in a horrible parody of the childhood game of Hot Potato. Water was so scarce on the European side that they tanked it in from Egypt. ( That's a long water run. Look at a map.)

The campaign was a military stalemate paid for by heavy losses on both sides, but it was a formative event for three modern nations: Australia, New Zealand and Turkey. Today the Gallipoli National Historic Park is a pilgrimage site for all three countries.

My Own True Love and I traveled to Gallipoli from Istanbul in a tour bus. Many of our fellow travelers that day were New Zealanders and Australians whose father/uncle/grandfather/great-grandfather had fought at Gallipoli. (ANZAC Day is a national holiday in both Australia and New Zealand commemorating the landing of Australian and New Zealand forces.) Our tour guide was a retired Turkish naval captain for whom Gallipoli was a lifelong passion. The museum was heart-breaking. You could walk the trenches in the battlefield. The memorial honored the soldiers from both sides. The combination was magical.

But the thing I remember most clearly is the end of the day. Every tour of the Gallipoli National Historic Park ends in front of a statue of the oldest Turkish survivor of the battle and his young granddaughter, who holds a bouquet of rosemary for remembrance. He is said to have told his granddaughter that every man who died at Gallipoli is part of Turkey now and should be honored. Visitors add rosemary springs to the granddaughter's bouquet from bushes that surrounded the memorial. Because My Own True Love held the highest military rank of anyone on our bus, Captain Ali invited me to step forward to add a spring of rosemary to the bouquet on behalf of our group. Did I get all teary? You bet.

Remembrance is, ultimately, why we visit battlefields. Remembrance of those who died and those who survived, of causes lost and causes won, of the reasons we go to war, of greed, honor, bravery and shame. Remembrance of the world we have lost on the road to today.

What battlefield visits made an impact on you?