In Search of Sir Thomas Browne

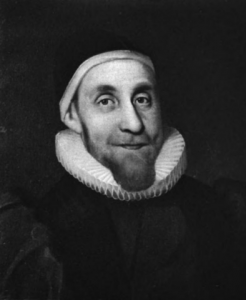

There are times when the book I read isn’t the book I think it’s going to be.* This happened to me recently with science writer Hugh Aldersey-Williams’ In Search of Sir Thomas Browne. I expected a biography. And I had Browne confused with someone else altogether, though I am no longer sure who. Possibly Robert Burton, the author of The Anatomy of Melancholy?

- Robert Burton

- Sir Thomas Browne

I got a quirkier and more interesting book than I was expecting.

In Search of Sir Thomas Browne: The Life and Afterlife of the Seventeenth Century's Most Inquiring Mind is neither a biography of Browne nor a critical study of his writings. Instead it is the intellectual equivalent of a buddy road trip.

Aldersey-Williams became interested in Sir Thomas Browne--a physician, scientist and debunker of popular myths--more than 20 years ago. In the intervening years, he found himself stumbling over Browne at unexpected moments. Finally, feeling "haunted" by Browne, he decided it was time to haunt Browne in return. Using Browne's writings, rather than his life story, as a framework, Aldersey-Williams travels in the physician's footsteps, both literally and intellectually. He looks for traces of Browne's life in modern Norwich (home to both men) and explores the echoes left by Browne's varying preoccupations in modern thought. He explores questions of scientific certainty, uncertainty and error, the meaning of order in nature, the reconciliation of science and religion, and the extent to which truth is knowable. He uses Browne's fascination with the recurring form of the quincunx,** his efforts at cataloging the birds of the Norwich marshes and his role as the expert witness in a witch trial as tools for understanding the intellectual landscape of both the 17th century and the modern world.

In the end, Aldersey-Williams argues that Browne is important not because of his answers or his baroque prose style, which inspired writers as diverse as Ralph Waldo Emerson and Jorge Luis Borges, but for the questions he asks.

* I’m not the only person this happens to, right?

** An arrangement of five objects with four at the corners of a square or rectangle and the fifth at its center

Most of this review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

Rival Queens

Nancy Goldstone has made a career of telling the often forgotten and always dramatic stories of powerful women in medieval Europe.* In The Rival Queens: Catherine de'Medici, Her Daughter Marguerite de Valois, and the Betrayal That Ignited a Kingdom, Goldstone turns her attention to Renaissance France and its role in the growing struggle between Catholics and Protestants across Europe.

The betrayal to which the title refers is the infamous St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre, in which thousands of French Huguenots were killed when they gathered in Paris to attend the unwilling Marguerite's wedding to her Protestant cousin, Henry of Navarre. In fact, the massacre is only the most extreme of the betrayals--personal and political alike--which Goldstone describes.

Goldstone overturns the ruling historical evaluation of Catherine as an able, if Machiavellian, ruler and Marguerite as a sensual dilettante. Instead, she shows Catherine manipulating her children in order to maintain her power in France. Marguerite stands in counterpoint to her, growing into a woman of courage and integrity. Goldstone makes a compelling case for both portrayals, using first-hand accounts from the period, including Marguerite's memoir.

Firmly rooted in history, The Rival Queens combines the pageantry and passion of a Philippa Gregory novel with the Byzantine plot and violence of A Game of Thrones. It is a story of intra-family rivalry taken to the level of "scheming and conspiracy, treason and treachery". Religion is its battlefield; sex, tale bearing and the withholding of maternal love its primary weapons.

*Including The Maid and the Queen, yet another contemporary retelling of Joan of Arc's story.

This review appeared previously in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

From The Archives: Squeeze This!

I know it's hard to believe, but even history bloggers sometimes think about something other than history. We knit, canoe, wrestle bears, feed people, drink whiskey, and play with the cat.* Whenever we get the chance, My Own True Love and I pull on our dancing shoes and two-step and waltz to a Cajun band.

I know it's hard to believe, but even history bloggers sometimes think about something other than history. We knit, canoe, wrestle bears, feed people, drink whiskey, and play with the cat.* Whenever we get the chance, My Own True Love and I pull on our dancing shoes and two-step and waltz to a Cajun band.

The heart of Cajun music is the accordion--a fiendish instrument by any standard. So when the editor at Shelf Awareness was looking for someone to review Squeeze This!: A Cultural History of the Accordion in America I waved my virtual hand in the air and squealed "Pick me!" (Oddly enough, no one fought me for it. Go figure.)

Ethnomusicologist Marion Jacobson's Squeeze This! is a serious work of musical and cultural history written in an engaging and accessible voice. **

Jacobson goes beyond a consideration of the accordion as physical artifact. Writing in the tradition of Paul Berliner's The Soul of Mbira and Karen Linn's That Half-Barbaric Twang, Jacobson also looks at how the accordion operates in social, cultural, and symbolic terms.

Squeeze This! begins with Jacobson's inadvertent introduction to America's "accordion culture" and ends with the modern accordion revival, which repositions the often-derided instrument "as avant-garde, edgy, even sexy". In between, she discusses how the role of the accordion in American society evolved in response to changes in immigration law, the death of vaudeville, the rise of radio, the invention of the electronic microphone, cultural assimilation, cultural preservation, and the youth culture of the 1960s. She traces the rise and fall of the accordion in popular culture through the careers of the musicians who play it, from Guido Deiro to Weird Al Yankovic.

Possibly the most interesting portion of the book is Jacobson's exploration of the accordion as "a low-tech, anti-postmodern antidote to synthesizer saturation". Subversion, the search for authenticity, and the contrast between images of female sexuality and male nerdiness are not topics commonly associated with the accordion and accordion players.

Squeeze This! is not just a book about accordions. It will appeal to readers interested in both the development of American music, America's cultural history as a whole.

Now if you'll excuse me--I think I'll lure My Own True Love away from his desk for a quick two-step down the hall. They're playing our song.

The body of this review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers

* Note bene: I'm not claiming I do all of the above.

** Warning for Cajun music enthusiasts and other fans of the button accordion. Jacobson focuses almost entirely on the piano accordion. Squash down your prejudices and read the book anyway.