The Fall of the Ottomans

Last year I spent a lot of time and virtual ink on books about World War I. When the year came to an end, I had to take a breather. But this one was too good to let pass:

Rogan's story is as complicated as the multi-ethnic empire at its heart. He describes the forces of internal revolution, external wars, lost provinces and lost confidence that led the Ottomans to seek an ally against Russian aggression in the early months of 1914--and how those same forces shaped Ottoman choices throughout the war. He tells the familiar stories of Gallipoli and the Mesopotamian campaign from an unfamiliar vantage point and the less familiar story of Turkey's fight against Russia on the Caucasian front.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the book is the recurring question of the relative power of Islam, national identity and ethnicity within the Ottoman world, beginning with Germany's unfulfilled hope that the Ottoman declaration of war would be seen as an act of jihad, thereby triggering rebellions among Muslim subjects of the British and French empires.* Rogan handles the tricky subjects of jihad, secularism, Arab nationalism, and Turkish paranoia about a possible Armenian fifth column with historical precision and a keen awareness of their implications for the modern world.

* I first came across this idea in John Buchan's Greenmantle. Greenmantle is one of my favorite novels, but I always thought the concept was over the top. I was stunned to discover that it was an actual piece of German policy--minus some of Buchan's wilder flourishes.

The guts of this review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers

“Oriental” Jones

Sir William Jones (1746-1794), known to his contemporaries as “Oriental” Jones, was one of the great eighteenth century polymaths. He was a linguist, what was then called an Orientalist,* and a successful public intellectual--the kind of scholar who is able to make abstruse topics not only accessible but exciting.

Jones started early with his love of language: he reportedly learned Persian from a Syrian merchant in London and translated the poems of Hafiz into English at the age of sixteen . Over the course of his life he studied twenty-eight languages including not only Latin and Greek, but German, French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian and Turkish, several South Asian languages, and a smattering of Chinese.

By the time he received his bachelor of arts from Oxford in 1768, Jones had already become known as a scholar of all things “Oriental”--by which he and his contemporaries meant South Asia and the Middle East. The King of Denmark hired him to translate a biography of the emperor Nadir Shah from Persian into French. Published in 1770, the translation secured Jones’ reputation as translator and linguist. He was only 24.

Over the next thirteen years, Jones published a number of works related to the language and culture of the Islamic world , including the authoritative A Grammar of the Persian Language (1771), which he later translated into French, and a translation of seven famous pre-Islamic poems from Arabic that Tennyson later claimed as an inspiration . During this period, he also published a volume of his own poetry , in which he combined classical conventions with Islamic themes and imagery. (Anyone feeling a tad inadequate at this point will be pleased to know that his poems are workmanlike but not inspired. His biographer describes them as “minor classics”, but that’s generous.)

Like many a modern adjunct professor, Jones soon found it was difficult to make a living as an independent scholar, so he turned to the study of law. He was called to the bar in 1774. Working as a barrister, an attorney, and an Oxford fellow, he made a name for himself as a legal scholar and translated manuscripts in his spare time. He also became known for his pro-American sympathies, traveling to Paris three times during the American Revolution to meet with Benjamin Franklin regarding the military and political situation. In fact, it was rumored that he intended to emigrate America to help write the new country’s constitution. (The mind boggles at the image of Jones and Madison in collaboration.)

It was perhaps inevitable that a cash-strapped attorney with a talent for languages and a fascination with the Orient would end up in India in the service of the British East India Company.** Jones was engaged to be married,but didn’t have the income to support a wife. When a lucrative job as a judge on the supreme court of the British East India Company’s Bengal Presidency became available, he asked his friends to help him secure the position. Evidently his reputation as a legal scholar and Orientalist outweighed his reputation as a pro-American troublemaker. In 1783, Jones and his new wife sailed to Calcutta.

If Jones had not already earned the nickname “Oriental”, he certainly deserved it after his arrival in India. Many employees of the British East India Company hired local instructors to help them with Bengali, Hindi or Persian. Jones took the unusual step of adding Sanskrit to the list, making him the second Englishman known to have learned the language. During his eleven years in Calcutta, Jones founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal--a Calcutta variation on the Royal Society with an emphasis on “oriental” subjects. In addition to his semi-official work on Indian legal systems, he wrote extensively on Indian history, religion, languages, literature, botany and music. He translated a number of works of Indian literature into English, including Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda , the collection of fables known as the Hitopadesa, and the Laws of Manu, the first step in a compilation of Hindu and Muslim law intended to improve justice in British courts in India.

His most influential translation was Sakuntala, the masterwork of fourth century Indian poet and playwright Kalidasa, whom Jones described as “the Shakespeare of India”. Published in 1789, Jones’ Sakuntala went into five editions in twenty years--a best seller in eighteenth century terms--and was translated into German in 1791 and French in 1803. It is considered one of the most important influences on the first generation of Romantic poets

Most important, his study of Sanskrit led Jones to postulate a common source for what came to be known as the Indo-European languages. In his 1786 presidential discourse to the Asiatic Society, Jones described the relationships he had found between Sanskrit, Latin and Greek, which he believed were too strong to be accidental, and suggested that they not only had “some common source, which perhaps no longer exists”, but were also related to the Gothic, Celtic and Persian languages. That single paper was the beginning of comparative philology

Jones died in Calcutta in April, 1794, exhausted by his twin pursuits of legal studies and Orientalism. His digest of Indian legal systems was incomplete, but he had effectively founded the academic disciplines of comparative philology and Indology (South Asian studies in modern college catalogs) and introduced the first generation of Romantic poets to a broader vision of the world.

* For purposes of this blog post, I am going to ignore the complications that now surround the term Orientalism. Otherwise we’ll be here all day.

**Just a reminder, at this point India was not a colony of the British government. The British East India Company held the right to administer various regions of the subcontinent as a vassal of the Mughal emperor. While this would increasingly become no more than a political fiction, in the 1780s it was still very much a political reality.

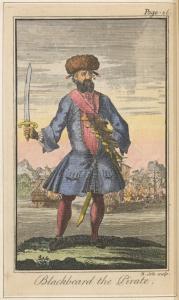

From the Archives: When Is A Pirate Not A Pirate?

I currently have my head down trying to finish a big project that I'm excited about. Instead of driving myself crazy trying to write blog posts at the same time or, worse, "going dark" I'll be running some of my favorite posts from the past for the next little while. Enjoy. And I'll see you soon.

When is a pirate not a pirate? When he's got a license to steal.

From the 16th through the mid-19th centuries, governments issued licenses, called letters of marque, to private ship owners that gave them permission to attack foreign shipping in times of war. Called privateers, these government-sanctioned pirates were an inexpensive way for governments to patrol the seas. Private investors outfitted warships in the hope of earning a profit from plunder taken from enemy merchants.

Unlike pirates, privateers had rules they had to follow. They were only allowed to attack enemy ships during times of war. Sometimes their commissions limited them to a specific area or to attacking the ships of a specific country. In exchange for following the rules, they would be treated as prisoners of war if they were captured.

In fact, it was sometimes hard to tell a privateer from a pirate. If a privateer attacked foreign shipping in peace time, interfered with the ships of neutral countries, or was just too violent, he was sometimes treated as a pirate if he was captured. Some privateers, like Sir Francis Drake, became national heroes. Others, like Captain William Kidd, were hanged as pirates.

Privateering was made illegal in 1856 by international treaty.

Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.