From The Archives: Why I Want To Go To Omaha

I currently have my head down trying to finish a big project that I'm excited about. Instead of driving myself crazy trying to write blog posts at the same time or, worse, "going dark" I'll be running some of my favorite posts from the past for the next little while. Enjoy. And I'll see you soon.

Aquatint by Karl Bodmer. Fort Pierre on the Missouri and the adjacent prairies c. 1833

Why is Omaha on my travel list? Two words, okay three: The Bodmer Collection.

In 1832, German naturalist Prince Maximilian zu Weid-Neuweid led one of the earliest expeditions to the American West.* As anyone who has snapped a picture of the Grand Canyon or the Grand Bazaar knows, expeditions need to be recorded. Instead of a Canon Powershot, Prince Maximilian brought along Karl Bodmer, a young Swiss artist with a talent for watercolor.

Prince Maximilian and Bodmer traveled the rivers of the American West for two years, going from Saint Louis to North Dakota and back. They saw an Indian raid, a wild prairie fire, and herds of buffalo and elk at close range. They suffered through a harsh winter in North Dakota, trapped by snow and bitter cold. At one point their boat caught fire.

Bodmer painted through it all, even when it was so cold that his paints froze solid. He captured images of the landscape, the animals, and. most notably, the Native American peoples they met. Bodmer’s depictions of the early American West have been described as the visual equivalent of Lewis and Clark’s journals. Although originally intended as “notes” to Prince Maximilian’s account of their journey, Bodmer’s paintings and sketches are now seen as the most important work of the expedition.

Today the Bodmer Collection is housed at the Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska. Put it on your list.

*Prince Maximilian wasn't just a rich man with a yen for travel. He had a bee in his bonnet. He thought the native peoples of the Missouri and Mississippi river basins would help him prove that humankind developed from a single set of parents, presumably Adam and Eve.

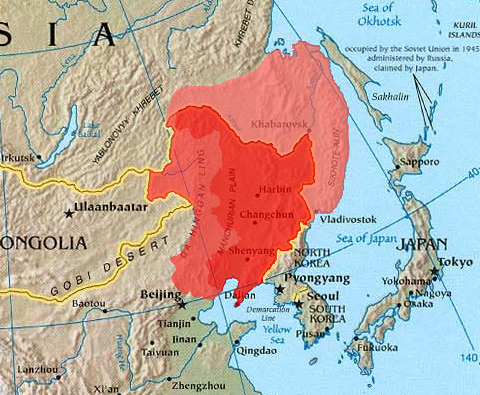

In Manchuria

Michael Meyer's In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland And The Transformation of Rural China is a beautifully written blend of memoir, travel account, history and social commentary.

In 2011, Meyer moved to his Chinese wife's hometown--a Manchurian village with what proved to be the inappropriate name of Wasteland. He had lived in Beijing for several years and written about change in urban China (The Last Days of Old Beijing). Now he was interested in the question of rural China, which was slowly disappearing as a result of forces familiar to anyone who knows the blighted farm towns of the American Midwest.

In his account of his months in Wasteland, Meyer walks the fine and often funny line between being both insider and outsider, telling a story that is at once intensely personal and broadly political. He explores the unexpected agricultural richness of Wasteland, learning the fine points of rice cultivation in the process. He searches for the surprisingly illusory traces of Manchuria's history as China's frontier. (Only remnants remained of the Manchu dynasty's Willow Palisade, Japanese and Russian colonial cities, and a POW camp where survivors from the Bataan Death March were held.) And to his surprise, having expected to find the remains of China's past in Manchuria, he instead finds China's future in the form of Eastern Fortune-- a privately owned rice company that is in the process of transforming Wasteland from a commune to a company town.

In Manchuria is an engaging account of rural China poised on the brink of change.

This review previous appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers

The End of French Algeria

Barricades in Algiers, 1960

Photograph courtesy of Christophe Marcheux under Creative Commons license

The Algerian Revolution, which lasted from 1954 to 1962, was one of the bloodiest of the anti-colonial wars that broke out in Asia and Africa after the end of World War II. *

Algerian resistance against colonial rule in Algeria was nothing new. Abd al-Qadir fought against French expansion in North Africa for fifteen years in the mid-nineteenth century. And small-scale uprisings were a regular occurrence throughout the French colonial period.

But Algerian resistance took on a new face after World War II. The war had weakened France and reduced its authority in the empire. On May 8, 1945, when French Algerians celebrated Germany’s surrender, Algerian nationalists staged a protest against a return to French rule that resulted in a small Algerian uprising and brutal French retaliation.

In years immediately after the war, the French government attempted to negotiate with the elite-based nationalist movement by offering a small degree of political reform--a classic case of too little, too late. Algerians rejected French offers as a ruse to maintain minority French rule over a Muslim majority ten times its size. For those of us familiar with the Indian nationalist movement, this all sounds very familiar. What came next was very different from the Indian experience.

A growing number of nationalists came to believe armed insurrection was the only way to get the French out. On November 1, 1954, only a few months after the crushing defeat of French troops by Vietnamese nationalists at Dien Bien Phu,** the National Liberation Front (FLN) called for independence from France. The organization requested diplomatic recognition for the establishment of an Algerian state from the United Nations. At the same time, the FLN began a guerilla war against French control.

France was not willing to let Algeria go easily. The interior minister, François Mitterand , summed up the popular French position, “Algeria is France”. He then declared “the only possible negotiation is war.” Not surprisingly, war is what he got.

The trigger point for escalating violence on both sides occurred in August, 1955, when the FLN, which had previously targeted public buildings, military and police posts, and communications installations, attacked a small European mining settlement near the city of Phillipeville. The nationalist forces slaughtered seventy-one European civilians, including a five-day old baby. The attacks were up close and personal: slitting a civilian’s throat is not generally recognized as an act of warfare. The French army went on a killing rampage in response, shooting down as many as 12,000 Algerians--more than the entire membership of the FLN.

Like most wars of independence, the Algerian Revolution was a David and Goliath contest, with the caveat that both sides were ruthless. With limited resources, the FLN fell back on the tactics of guerilla warfare: planting bombs in public places, ambushing government forces, killing and then blending back into the civilian population. Determined to protect the large community of European settlers in Algeria, the French government increased its military presence to 500,000 troops. French tactics in the Algerian War were shaped by their recent defeat in Vietnam, where many of the officers had served. These tactics included the use of napalm, the large-scale destruction of villages, and the relocation of almost two million Algerian civilians into so-called “pacification hamlets” in an attempt to cut the FLN off from its civilian base. *** The worst of the fighting occurred in Algiers itself, a bloody dance of FLN terrorist attacks and equally violent French counter-terrorism known as the Battle of Algiers.

By 1958, the French seemed to be winning the war in Algeria, but were losing the war at home. With the barbarism of the German occupation fresh in their memories, the French public began to question the methods used in the Algerian war, and the government that waged it. (Please note, this is not the same as questioning French rule in Algeria.) The government began to move toward compromise; the army and the pieds noirs did not.**** That April, former president Charles De Gaulle seized in power in a bloodless coup fueled by the Algerian paradox and backed in large part by the French settlers and pro-colonial elements of the army . The joke was on them. In 1959, de Gaulle pulled a political switcheroo and declared Algeria had the right to determine its own political future.

The Algerian War effectively came to an end on March 19, 1962, when the French government and representatives of the FLN signed the Évian Accords, which called for an immediate cease-fire and negotiations regarding the transfer of power to an Algerian government. A group of French Algerian extremists, with the tacit support of the army, launched a brief, brutal counter-terrorist campaign against both the FLN and the French government in Algeria in an attempt to stop the movement toward independence, but French control of Algeria was over. The French public approved the terms of the Accords in a referendum on April 8. On July 1, six million Algerians voted in favor of independence in a second referendum. Two days later, De Gaulle announced Algeria independence.

Following independence, some 900,000 pied noirs fled to France, which was totally unprepared for the flood of refugees. They left behind an economy shattered by 100 years of colonialism and eight years of war. Ironically, a few years later thousands of young Algerians began to leave their newly independent homeland in search of a better life--in France. French rule in Algeria was over; France’s relationship with Algerians was not.

* If you want a visceral depiction of the revolution, I recommend you skip my post and go straight to the 1966 film The Battle of Algiers by Italian filmmaker Gillo Pontecorvo. I have not seen it, because I am a wimp about filmed violence, but by all accounts, it is a powerful work of art that looks at the war from both sides.

**If you’re interested in learning more about the siege of Dien Bien Phu or the background for the US involvement in Vietnam, My Own True Love and a great many other history buff, recommend Bernard Fall’s Hell In A Very Small Place. It’s on my personal To Be Read list. (I'm less of a wimp about violence in the written word.)

***A civilian internment camp by any other name is still morally questionable.

****It is important to point out that European settlement had been a fact of Algerian life for almost 100 years under French rule. Many of the European settlers were second and third generation pied noirs. They might have thought of themselves as French but their feet were deeply rooted in Algerian soil. The parallels with white South Africans are instructive.