When Paris Went Dark

When Nazi troops marched into Paris in June, 1940, the city surrendered without firing a shot.*

In When Paris Went Dark: The City of Light Under German Occupation, 1940-1944 , historian Ronald C. Rosbottom explores face-to-face interactions between occupiers and occupied, the effect of the Occupation on daily life in Paris, its psychological and emotional impact on Parisians and its legacy of guilt and myth.

Drawing from official records, memoirs, interviews and ephemera, Rosbottom tells a story that is more complicated than simple opposition between courage and collaboration, though he offers examples of both. He discusses the fine line between survival and collaboration, the distinction between individual acts of resistance and the Resistance and how occupiers and occupied utilized the hide-and-seek possibilities of Parisian apartment buildings. He considers the act of waiting in line both as an illustration of the difficulties of everyday life and as a replacement for forbidden political gatherings. Above all, he describes the Occupation as gradual constriction of Parisian life within ever-narrowing boundaries.

Rosbottom does not limit his discussion to the Parisian perspective. Some of the most interesting sections of When Paris Went Dark deal with the German experience in the city, a complex mixture of tourism, conquest, envy and isolation. His account of Hitler's early-morning tour of the capital soon after its surrender is particularly illuminating about the Nazi Party's ambivalence toward cities in general and Paris in particular.

When Paris Went Dark is an important and readable addition to the social history of World War II.

*I will admit with only the slightest embarrassment that when I think "Nazi occupation of Paris" the images that come to mind are straight out of Casablanca. That will probably never change. Because putting pictures in our heads--accurate or not--is one of the things great art does.

Most of this review appeared previously in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

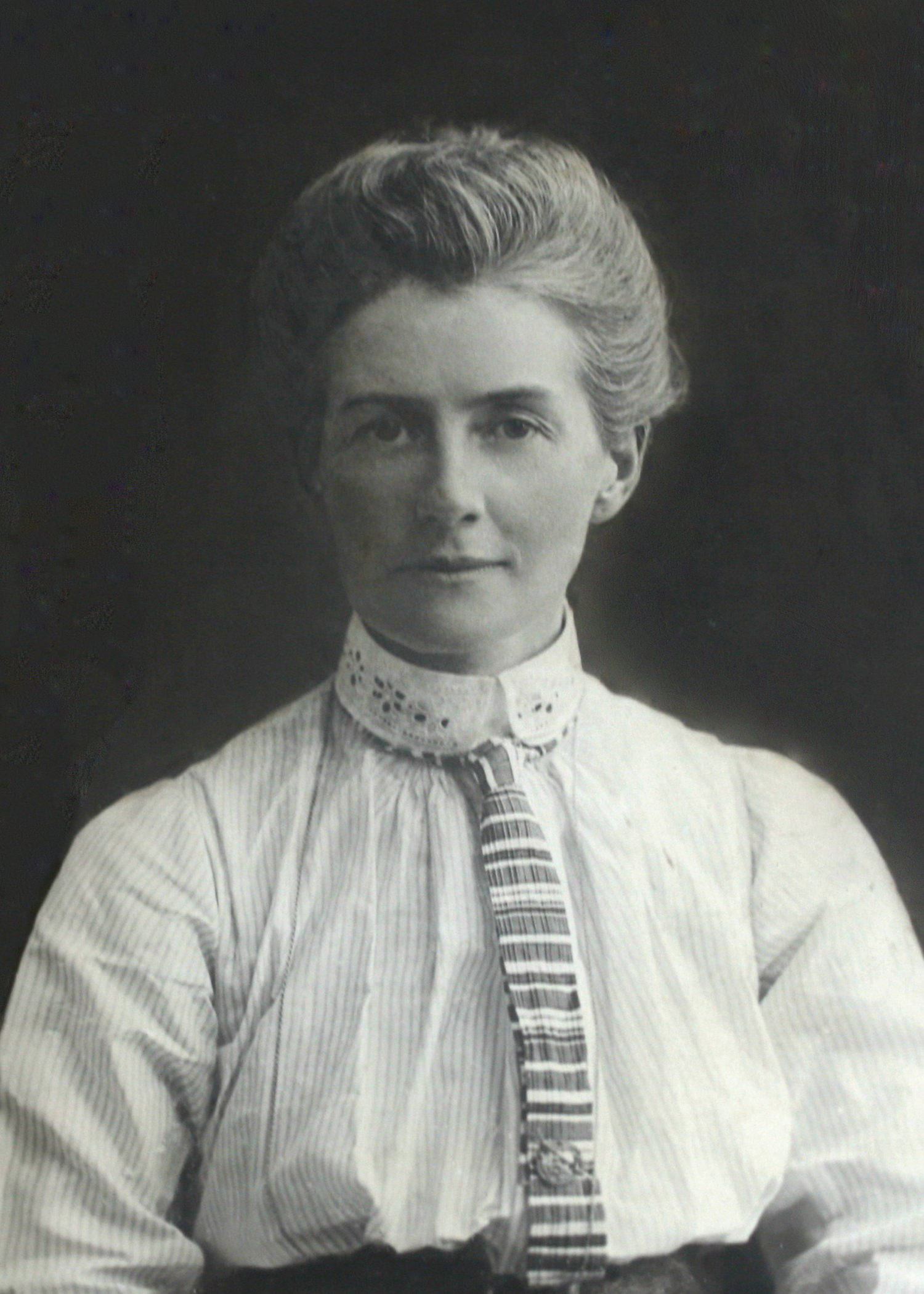

Edith Cavell: “Patriotism Is Not Enough”

Not all the heroes of the First World War fought in the trenches.

Forty-nine year old British nurse Edith Cavell was the director of the first nurses' training school in Belgium. When Germany occupied Brussels in the first month of the war, Cavell refused to leave. She turned her clinic into a Red Cross hospital and cared for wounded soldiers from both armies.

On November 1, 1914, Cavell took her heroism to a new level when a Belgian resistance worker brought two British soldiers to her door. Hiding Allied soldiers was punishable by death, but Cavell took the soldiers in without question. She hid them for two weeks while plans were made to take them across the border into the Netherlands, which remained neutral throughout the war.

These two soldiers were the first of more than 200 Allied soldiers whom Cavell helped escape from German-occupied Belgium during the first year of the war. Working with a resistance network, she provided medical care for wounded soldiers, hid the healthy until a guide could escort them over the border, and made sure they had money in their pockets for the journey.

Catching Cavell in the act became a priority for the German political police, who assigned an officer to the task full-time. Searches of the clinic became more frequent. (On one occasion she hid a wounded soldier in an apple barrel, covered with apples.)

On August 5,1915, the Germans arrested Cavell. Told that the other prisoners had confessed, she admitted during interrogation that she had used the clinic to hide Allied soldiers. Ten weeks later, Cavell and 34 other resisters were tried for assisting the enemy. Five, including Cavell, received the death penalty.

American and Spanish diplomats tried to get her sentence commuted without success; her execution was scheduled to be carried out the next day at dawn. When an English chaplain visited her that night to offer her comfort, he was surprised to find her calm and collected. Cavell told him, "I realize that patriotism is not enough, I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone." As he left, Rev. Gahan told her,"We will always remember you as a heroine and a martyr." Cavell answered, "Don't think of me like that. Think of me only as a nurse who tried to do her duty."

Cavell's hope to be remembered "only as a nurse" was idealistic--and unrealistic. The British propaganda office at Wellington House used her story both to increase enlistment in Britain (the number of volunteers doubled in the weeks after her death) and to increase anti-German sentiment in the United States.

Two Stories In One?

Dear Readers,

I'm hoping you can help.

I'm in the initial stages of writing a new book proposal. Or more accurately, I'm in the initial stages of writing three book proposals springing from the same big topic in an effort to decide which one works best.* The structure of two of the proposals is straightforward, but the third is problematic: parallel events that occurred in very different times and places.

I'm looking for models of historical works that have successfully used two stories, either combining them in a single narrative or linking two separate narratives.

The first example I looked at is Simon Schama's Dead Certainties (Unwarranted Speculations). The book is beautifully written, but I found it perplexing until the end--not necessarily a condition I want to inflict on readers. The first section, "The Many Deaths of General Wolfe" looks at the death of General Wolfe on the Plains of Abraham in 1759 from several different vantage points, including that of nineteenth century historian Francis Parkman. The second section, "Death of a Harvard Man" tells the story of the murder of Dr. George Parkman in Boston in 1849. For most of the book, the two are linked by a single reference in the first section to "Uncle George Parkman" and the general theme of death. Schama finally shares the element that joins the two stories together on page 320 of the 327 page book: "Both the stories offered here play with the teasing gap separating a lived event and its subsequent narration…These are stories, then, of broken bodies, uncertain ends, indeterminate consequences." It's all very clever,** but the connection comes so late in the book that it's not very satisfying as narrative. Kind of like a murder mystery where the author holds back a vital clue so the reader has no hope of solving the puzzle.

Eric Larsen's Devil In The White City is the obvious next choice, but it seems to be in one of the boxes we have not yet unpacked.

Any suggestions of other possible models I could read while I dig through the boxes?

Many thanks.

*Not very efficient, but sometimes the only way I can find out what I think/know/believe is to write my way through.

**Just for the record, I'm not being sarcastic. It's a lovely and illuminating piece of deconstruction.