Review: The Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42

I've written on this blog before about the first British invasion of Afghanistan, and the disasters that followed. In fact, I've written about it more than once. It's a story that never fails to fascinate me, but when I received William Dalyrmple's The Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42 to review I was afraid I wouldn't have anything new to say.

Wrong.

In White Mughals and The Last Mughal, William Dalrymple introduced readers to the complicated relationships between South Asian rulers and the British East India Company in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. He returns to that world in The Return of a King: The Battle for Afghanistan, 1839-42. As in his earlier works, Dalrymple reveals a version of "British India" that is not merely, or even primarily, British.

The story of the First Anglo-Afghan War has been told often and well, most recently by Diane Preston in The Dark Defile. Previous writers have focused primarily on the tangle of misinformation, paranoia and bad decisions that led to the destruction of the Army of the Indus by Afghan forces. Dalrymple broadens the story. Using not only new sources from British participants, but an array of Russian, Persian and previously unknown Afghani sources, he describes the war from both a British and an Afghani perspective. Readers already familiar with the details will be fascinated in particular by excerpts from the memoir of Shah Shuja; the deposed Afghan ruler whom the British attempted to return to the throne as a shield against Russian expansion appears as more than a shadow puppet for the first time.

Written in an engaging narrative style, The Return of a King is a nuanced account of what one of the expedition's survivors described as "a war begun for no wise purpose." The inevitable analogy with modern events at the end of the book is clumsy by comparison.

This review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

Road Trip Through History: The Vandalia Statehouse State Historical Site

The first thing you need to remember about the old state capitol building in Vandalia, Illinois, is that it is NOT called the Old Capitol.* The Old Capitol, which is not as old as the state capitol building in Vandalia, is in Springfield. What can I say? Stuff doesn't always make sense.

Vandalia became the second capitol of the new state of Illinois in 1819**, but it didn't remain the seat of government for long. The Federal-style building that stands today was the third statehouse in Vandalia, built in 1836 in response to a referendum to move the capitol from Vandalia to Springfield. Building a new statehouse wasn't enough to stop the move. In 1837, Springfield was chosen as the permanent location for the state capitol. The supporters of other locations immediately lashed out with charges of corruption against Springfield-area legislators, most notably "Honest Abe" Lincoln, then in his second term as a state representative and a major Springfield-booster.

Modern Vandalians are happier with Mr. Lincoln than their 19th century predecessors were. Today you can have your picture taken with him.

The site is historically important for its relationship to Lincoln, who began his political career there, but the tour guides don't limit themselves to Lincoln lore. Our guide served up a tasty mix of historical odd bits, the day-to-day practice of government in a frontier state, and a nineteenth century political scandal ***

If you're in the area and looking for a history break, you can't go wrong with the Vandalia Statehouse State Historical Site.

* Actually, the first thing you need to remember is that the town is Vandalia, not Vidalia, which is the place in Georgia where the onions come from. My Own True Love corrected me on this several times, though he assures me that I didn't make the mistake when talking to any of the wonderful people who answered my questions in Vandalia. If I did, I apologize. I knew where I was but I was goofy with cold medicine.

**The first capitol was at the French colonial town of Kaskaskia.

*** Theopholis Smith, a supreme court justice and the first Illinois public official to be impeached--for trying to sell a seat in the legislature. Who would have thought such a thing could happen in Illinois?

Speaking of book storage…

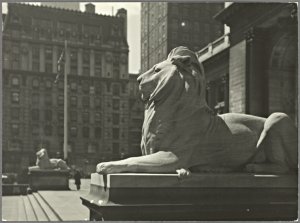

For the last five years I’ve visited New York City in April to attend the American Society of Journalists and Authors annual meeting. Every year I’ve made a pilgrimage to Fortitude and Patience, the stone lions that stand outside the public library on 5th Avenue. This year I finally went inside--as part of an ASJA field trip. The library gave us a double treat: an introduction to its research resources and a private tour.

Even from the perspective of someone who has spent hundreds (maybe even thousands) of hours at the University of Chicago’s wonderful Regenstein Library, the New York Public Library’s resources are pretty dang impressive. Four research libraries (plus 87 circulating branches) linked by a single catalog, an astonishing off-site book storage facility, special collections galore, and access to many, many on-line databases. Not to mention gorgeous reading rooms.

When they told me I could have a library card even though I don’t live in New York, I said, “Sign me up!”

The tour was a history nerd’s delight: a combination of stories about the past, architectural trivia, and glimpses of the library’s future use as a circulating library. Here are some of the highlights:

• The marble in the main hall is the same as that used to build the Parthenon, after all the library was meant to be a temple of learning

• The building was designed with an eight-room apartment for the building’s janitor and his family. (Can you imagine growing up with the library just downstairs?)

• We got to go down in the stacks, something not allowed on the public tours. Look carefully and you’ll see something missing: books! Most of them have been moved to an off-site storage facility designed for book preservation. These days you need to request books the day before you need them.

Now that I've found my way inside, you can be sure I'll be back.