Road Trip Through History: The Battle of Hastings

Image courtesy of Antonio Borillo

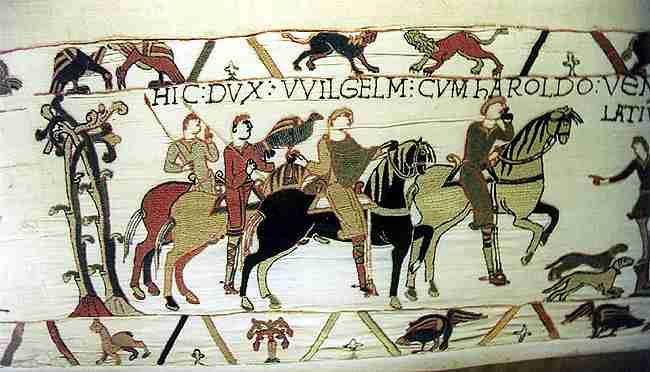

On October 13, thousands of history enthusiasts from around the world arrived at the British town of Battle to re-enact the Battle of Hastings. (You know, William the Conqueror, 1066, and all that.)

My Own True Love and I weren't there.* Just as well. The weather was cold and wet. The battlefield conditions were so muddy that the organizers called off the second day of the battle because the ground was too muddy for vehicles to get in and out. (I suspect any number of Anglo-Saxon and Norman soldiers at the original battle would have been pleased if someone had called off the second day of the real battle.)

When we arrived, a week later, the battlefield was still a muddy mess. We happily went through the excellent introductory exhibit, learning about Anglo-Saxon England, the Duchy of Normandy, and why William the Bastard of Normandy** thought he had a claim to the English crown.***

Then we headed to the battlefield, audio tours in hand. Before we got to the first point on the tour, we were slipping in the mud on the path. My Own True Love's shoes sprang a leak. Defeated by the mud, we retreated to the café, where we drank coffee, listened to our audio tours, and envied the rubber boots worn by the squadrons of British school children trooping past.

You can get a detailed account of the battle here. These are the elements that struck me:

- Both sides were descendents of Viking conquerors. The rulers of England were the descendents of King Canute of Denmark. The Normans were Norwegian Vikings with a French accent.

- The battle was a classic stand off between infantry and armed horseman: immovable object vs. irresistible force.. The English army, on foot, depended on the strength of its shield wall. The Normans enjoyed the mobility of cavalry. William stumbled on a tactic that the Mongols (armed horsemen par excellence) would later use to confound Western armies. When his men panicked and retreated, exultant English troops broke out of formation to pursue them. William saw what was happening and ordered his flank to cut the English off. The pursuers were surrounded and slaughtered.. The first time was an accident. William learned; apparently the English didn't. When William ordered a feigned retreat to replicate his success, the English pursued again and were slaughtered again.

- The Battle of Hastings changed history, but it wasn't the only time France invaded England. Who knew?

Next stop, Brighton.

* We missed several special history nerd events as we drove along Britain's southeast coast--always a week too late or a week too early. We did, however, manage to arrive in Bath on the day of a major rugby match.

** The name was a legal description, not a character assessment.

*** William was a shirttail relative to Edward the Confessor, whose death in 1066 was the catalyst for the invasion. William's great grandfather was Edward's maternal grandfather.

The Thrill of the Vote

This post first ran on election day in 2008. My feelings on the subject haven't changed:

It's election day in Chicago. I just walked home from voting for a new mayor and a new alderman--and I miss my old neighborhood.

For ten years I lived in South Shore: a white graduate student/small business owner/writer in a neighborhood dominated by the African-American middle class. My neighbors were police officers, schoolteachers, fire fighters, electricians, and social workers. We didn't have much in common most of the year--except on election day.

As far as I'm concerned, voting is thrilling. My South Shore neighbors agreed. Voting in South Shore felt like a small town Fourth of July picnic. Like Mardi Gras. Like Christmas Eve when you're five-years-old and still believe in Santa Claus. No matter what time of day I went to vote, my polling place was packed. Voters and election judges greeted each other--and me--with hugs, high fives, and "good to see you here, honey". First time voters proudly announced themselves. Elderly voters told stories about their first election. People made sure they got their election receipts; some pinned them to their coats like a badge of honor. An older gentleman sat next to the door and said "Thank you for exercising your right to vote" as each voter left. The correct response was "It's a privilege."

Except for occasional confusion when the machine that takes the ballots jams, my current polling place is low key. Election judges are friendly and polite, but hugs are not issued with your ballot. When the young woman manning the machine handed me my receipt, she told me to have a good day. I said "It's always a good day when you get to vote." In South Shore, that would have gotten me an "Amen." In politically active, politically correct Hyde Park, it got me an eye-blinking look of surprise and a hesitant smile.

I started home, thinking maybe I was the only one in the neighborhood whose pulse beat faster on election day. A block from the polls I ran into a young man walking with a small boy, no more than six years old. The little boy stopped me, with a grin so big that he looked like a smile wearing a wooly hat.

"Did you vote yet?" he asked. "My dad is taking me to teach me how to vote."

"It's a privilege," I said.

He gave me the highest five he could manage.

* * *

So tell me, did you exercise your right to vote?