Sita Sings the Blues

The Ramayana is one of the classic Indian epics. Ascribed to the great Sanskrit poet-sage, Valmiki, it's a love story, a moral lesson, and/or a foundation myth, depending on what kind of reader you are. Boy gets girl. Boy loses girl to demon king. Boy rescues girl with the help of monkey-god. Boy worries that girl's virtue has been smirched and puts her to ordeal by fire. Girl comes through ordeal triumphantly. Boy bows to public pressure and banishes girl to the forest, where she gives birth to twin sons. Boy finds girl again and they live happily ever after.

The story has had an enormous impact on art and culture in India. It has inspired poets in almost every Indic language, most notably the version by 16th century poet Tulsidas. The folk play Ramlilla is performed all over India and the Hindu diaspora as part of the Dusshera festival. Rama and Sita are the romantic leads in countless Hindi movies. And in almost every case, the story focuses on Prince Rama--it is after all the Rama-yana.

In Sita Sings the Blues, American cartoonist and animator Nina Paley turns the spotlight on Sita. Her animated version of the story is colorful, complex and edgy. Using multiple animation styles, Paley interweaves a straightforward, if Sita-centric, version of the Ramayana with commentary on the story by a trio of modern Indians (represented by Indonesian shadow puppets), a modern-day story of a relationship gone wrong, and musical numbers that are part Bollywood and part 1920s jazz singer. The result is an engaging, often hysterical, feast for eyes, ears, and mind. *

Sita Sings the Blues is available on Netflix and Amazon and at Sitasingstheblues.com. **

*A word of warning: My Own True Love was not familiar with the story of the Ramayana and found the action a little hard to follow. If you're in his shoes, you might want to read this quick plot summary before you view.

** This review is entirely unsolicited. Ms. Paley doesn't know me from a water bug.

For those of you who subscribe by e-mail, click through to the blog home page if you want to see the trailer for the film, posted at the top of the page.

Alhazen: The First True Scientist?

Islamic scholar Abu Ali al-Hassan Ibn al-Haytham (ca. 965-1041), known in the West as Alhazen, began his career as just another Islamic polymath. He soon got himself in trouble with the ruler of Cairo by boasting that he could regulate the flow of the Nile with a series of dams and dikes. At first glance, it had looked like such a simple problem. But the more he studied it, the more impossible it seemed. Al-Hakim, known to his subjects as the Mad Caliph with good reason, was getting impatient. Alhazen only saw one way out: he pretended to be crazy. Safely confined as a madman until the caliph's death ten years later, Alhazen continued to work.

Time and isolation? It was the perfect situation for a man with a book to write.

While confined in his home, Alhazen revolutionized the study of optics and laid the foundation for the scientific method. (Move over, Sir Isaac Newton.) Before Alhazen, vision and light were questions of philosophy. Alhazen considered vision and light in terms of mathematics, physics, physiology, and even psychology. In his Book of Optics, he discussed the nature of light and color. He accurately described the mechanism of sight and the anatomy of the eye. He was concerned with reflection and refraction. He experimented with mirrors and lenses. He discovered that rainbows are caused by refraction and calculated the height of earth’s atmosphere. In his spare time, he built the first camera obscura.

Modern physicist Jim al-Khalili, in his excellent The House of Wisdom: How Arabic Science Saved Ancient Knowledge and Gave Us the Renaissance, calls Alhazen the greatest physicist of the medieval world, and possibly the greatest in the 2000 years between Archimedes and Sir Isaac Newton. His Book of Optics was first translated into Latin in the late twelfth or early thirteen century. It had an enormous impact on the work of western scientists from Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1292) to Isaac Newton (1642-1727)., calls Alhazen the greatest physicist of the medieval world, and possibly the greatest in the 2000 years between Archimedes and Sir Isaac Newton. His Book of Optics was first translated into Latin in the late twelfth or early thirteen century. It had an enormous impact on the work of western scientists from Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1292) to Isaac Newton (1642-1727). calls Alhazen the greatest physicist of the medieval world, and possibly the greatest in the 2000 years between Archimedes and Sir Isaac Newton. His Book of Optics was first translated into Latin in the late twelfth or early thirteen century. It had an enormous impact on the work of western scientists from Roger Bacon (c. 1214-1292) to Isaac Newton (1642-1727).

This post previously appeared in Wonders & Marvels

Log Cabins: Two Ways

I always learn something new when My Own True Love and I head out on a Road Trip Through History. Our recent expedition to Colonial Michilimacinac was no exception.

- I learned that eighteenth century cooks dried pumpkins as well as apples* and used pig bladders to seal crocks of prickled vegetables.

- I had long known that when push came to shove (so to speak) the bayonet was a more useful weapon than the musket to which it was affixed. I had not previously known that with repeated firing the sides of the bayonet became coated with a greasy toxin that meant soldiers stabbed with a bayonet were unlikely to survive even a flesh wound. **

- I was introduced to wall guns--a weapon that combined the blasting power of a cannon with the mobility of a musket. Obviously a besieged fort's best friend.

But the thing that struck me the most forcibly was the difference between how the British and the French built log cabins in the wilderness.

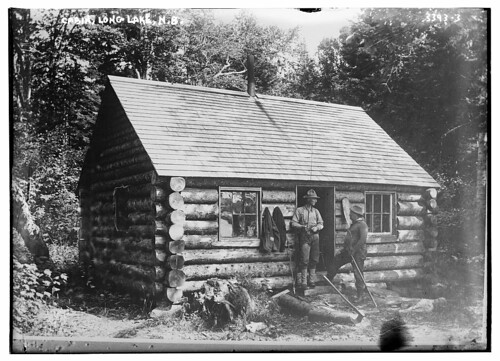

The Anglo-American log cabin style is what I picture when I think of log cabins: horizontal logs fitted together with notches and chinked with mud.

photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress

It is the form that evolved into WPA lodges, resort cabins, and Lincoln Logs.***

The French Canadian style of construction, known as poteaux en terre, or posts in the ground, used vertical timbers set into trenches, then weather-proofed with chinking and plaster.

It's a small difference, I know. But it somehow seemed emblematic of the larger differences of culture that exploded into violence along the borders of the British and French colonies--a subject I'll be coming back to in later posts.

*I may have learned about dried pumpkin before and simply blocked it out. I know it's un-American, but I do not like pumpkin and cannot understand wanting to preserve it for future use.

**I'm not sure why this came as a surprise. Until the commercial production of penicillin in WWII, infected wounds were a major cause of death in warfare.

***Invented by John Lloyd Wright, the son of architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Really. I was as surprised as you are.