Stranger Magic

I'm fascinated by the Arabian Nights. By the stories themselves and the way they fit together into their complicated frame story. By their transformation from Arabic street tales to a established position in the Western canon. By their echoes in Western culture, from the Romantic poets to Disney.

So I was delighted to get a chance to review historian and critic Marina Warner's new work on the tales.

Marina Warner's Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights is a multi-faceted study of the popular tales of wonder and magic known as the Arabian Nights.

Warner discusses the tales in the Arabian Nights with the interdisciplinary approach that she used to good effect in her earlier study of Western fairy tales, From the Beast to the Blonde. She examines them through the lenses of literary criticism, history, folklore studies, feminist theory and popular culture. She pays particular attention to the history of the Arabian Nights in the west, from the reception of the first translation from the Arabic by Antoine Galland in the eighteenth century through its influence in works as distinct as Mozart's operas and the Harry Potter books.

Not assuming that readers will have the same familiarity with "The Prince of the Black Islands" as they do with "Sleeping Beauty", Warner retells fifteen tales before she unravels them into their constituent themes, symbols and assumptions. She moves easily from the Biblical story of King Solomon to magic carpets, from the reputation of Egypt as the home of ancient magic to Sir Isaac Newton's alchemical experiments, and from the wealth of the Islamic world in the twelve century to post-Reformation anxiety about Catholic religious practices.

Warner succeeds once again in balancing entertainment with erudition. Like her earlier works, Stranger Magic is accessible enough for the general reader and rich enough to keep a specialist scribbling in the margins.

This review appeared previously in Shelf Awareness for Readers.

History on Display: Byzantium and Islam

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new Islamic gallery has been on my to-do list for this year’s trip to New York ever since it opened last November. It has some amazing pieces. But the exhibit that blew me away was Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition.

I want to make it clear right from the start: I know next to nothing about the Byzantine Empire. In my mental chronology, it’s basically a placeholder between the “real” Roman Empire and the rise of Islam. (I realize this is a wrong-headed and mistake positionn. We all have holes in our mental history of the world.)

The exhibit rammed me right up the sharp edges of my own ignorance. It gave me a broad-brush introduction to a multicultural empire that covered more territory than I realized. There were plenty of surprises. The one that had me scraping my jaw off the Metropolitan's marble-tiled floor was the Iconoclastic Controversy of the 8th and 9th centuries.

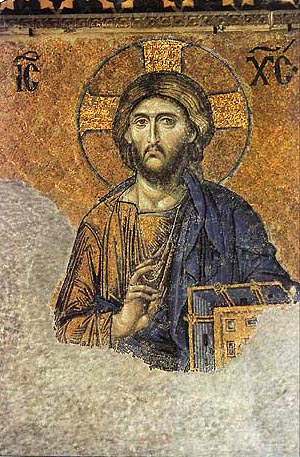

If you're like me, your mental image of Byzantium looks like this:

With that picture in my head, I find it hard to combine the words "Byzantine " and "Iconoclasm" in a sentence. And yet it appears that there was not just one period of Byzantine iconoclasm, but two. The First Iconoclasm lasted from 726 to 774 CE; the Second Iconoclasm from 813-842 CE.

During these periods, the Orthodox Church was torn by theological battles over the use of icons and images as objects of religious veneration. Imperial edicts forbade the creation or use of icons. In some parts of the empire, including Constantinople itself, existing images were plastered over*. Some iconoclasts took a more labor intensive approaching, carefully removing tiny mosaic tiles and jumbling them into a new, abstract pattern.

No one really knows what triggered the controversy. Some attribute it to an imperial attempt to seize control over the wealthy Orthodox Church. Others see it as a response to the rise and spread of Islam during the same period.

Whatever the reason, I was totally gobsmacked by this new insight into Byzantium. Anyone else had their historical certainties shaken up recently?

Updated: For those of you who can't make it to New York in the coming months, here's a wonderful slideshow of items from the exhibit from History Today.

City of Fortune

I thought I knew something about Venice. A floating city carved out of a malaria-ridden lagoon. Merchant city-state turned maritime empire, with one foot in the Muslim world. The European end of the desert caravan trade, with merchant entrepôts throughout the Levantine coast. Canals, gondoliers, masked balls, gold ducats. Glamor, wealth, decadence, decay. Or perhaps, in the words of Lerner and Lowe, "just a town without a sewer."

Then I got a chance to review Roger Crowley's City of Fortune: How Venice Ruled the Seas for Shelf Awareness and discovered I knew nothing about Venice.

Roger Crowley returns to the medieval and early modern Mediterranean in City of Fortune, using three defining moments to tell the story of Venice's development from a "smattering of low-lying muddy islets set in a malarial lagoon" to the greatest power in the region: the city-state's pivotal role in the Fourth Crusade and the sacking of Constantinople in 1204; the city's bloody rivalry with Genoa for control of the East-West trade; and its desperate defense against the Ottoman Empire's expansion into the Mediterranean in the fifteenth century.

As in his earlier books, Crowley's fast-paced narrative style and vivid character sketches strike a nice balance between the big picture and the telling detail. He tells the story using a variety of voices. In addition to accounts by Venetian doges, merchants and city officials, he uses those written by--often hostile--outsiders, including the poet Petrarch, Pope Innocent III, Norman crusaders, and Cretan rebels.

Trade is the theme that ties Crowley's story together. With no natural resources, no agriculture, and a small population, Venice depended entirely on trade for its survival. Its relationships first with Byzantium and later with the Islamic world were both the foundation of its prosperity and a source of contention with the rest of Christendom. Control of the western end of the overland trade caravans was the key to Venice's success as "Europe's first full-blown colonial adventure." Crowley ends with the event that would bring Venetian maritime dominance to a close: the news that Portugal had found a sea route to India, rendering the Venetian empire suddenly obsolete.

This review previously appeared in Shelf Awareness for Readers.