From the History in the Margins Archives: The Great Silence

Whether you know it as Armistice Day, Poppy Day, Remembrance Day or Veterans' Day, November 11 is a time to honor those who died in war and thank those who served.

The day of remembrance has its roots in the end of World War I. The war ended on November 11, 1918. When the word reached England that the the armistice had been signed, the country broke out into a spontaneous party. (The Savoy Hotel alone lost 2700 smashed glasses to the celebration.) No stiff upper lip allowed.

When the first anniversary of the Armistice drew near, dancing in the streets of a post-war world no longer seemed appropriate . Neither did letting the day go unnoticed. Some assumed that special church services were the proper response. Australian soldier and journalist Edward George Honey wrote a letter to the London Evening News suggesting a moment of silence "on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month". He asked for "Five silent minutes of national remembrance...Church services too, if you will, but in the street, the home, the theatre, anywhere, indeed, where Englishmen and their women chance to be, surely in this five minutes of bitter-sweet silence there will be service enough."

Honey asked for five minutes; he got two. King George V called for all Britons to stop their normal activities "so that in perfect stillness, the thoughts of every one may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the glorious dead."

If you can, at the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month--pause for a moment. If you can't? Thank a veteran. Buy a poppy, if you can find one. Pray for peace.

The Thrill of the Vote

This post first ran on election day in 2008. I've run it several times since then. My feelings on the subject haven't changed:

It's election day in Chicago. I just walked home from voting for a new mayor and a new alderman--and I miss my old neighborhood.

For ten years I lived in South Shore: a white graduate student/small business owner/writer in a neighborhood dominated by the African-American middle class. My neighbors were police officers, schoolteachers, fire fighters, electricians, and social workers. We didn't have much in common most of the year--except on election day.

As far as I'm concerned, voting is thrilling. My South Shore neighbors agreed. Voting in South Shore felt like a small town Fourth of July picnic. Like Mardi Gras. Like Christmas Eve when you're five-years-old and still believe in Santa Claus. No matter what time of day I went to vote, my polling place was packed. Voters and election judges greeted each other--and me--with hugs, high fives, and "good to see you here, honey". First time voters proudly announced themselves. Elderly voters told stories about their first election. People made sure they got their election receipts; some pinned them to their coats like a badge of honor. An older gentleman sat next to the door and said "Thank you for exercising your right to vote" as each voter left. The correct response was "It's a privilege."

Except for occasional confusion when the machine that takes the ballots jams, my current polling place is low key. Election judges are friendly and polite, but hugs are not issued with your ballot. When the young woman manning the machine handed me my receipt, she told me to have a good day. I said "It's always a good day when you get to vote." In South Shore, that would have gotten me an "Amen." In politically active, politically correct Hyde Park, it got me an eye-blinking look of surprise and a hesitant smile.

I started home, thinking maybe I was the only one in the neighborhood whose pulse beat faster on election day. A block from the polls I ran into a young man walking with a small boy, no more than six years old. The little boy stopped me, with a grin so big that he looked like a smile wearing a woolly hat.

"Did you vote yet?" he asked. "My dad is taking me to teach me how to vote."

"It's a privilege," I said.

He gave me the highest five he could manage.

* * *

So tell me, did you exercise your right to vote? It is indeed a privilege.

From the Archives: You think one vote doesn’t matter? Hah!

I have told this story here on the Margins before. But with the presidential elections only a few days away, I think it's important to remember right now that the 19th Amendment was ratified thanks to one man's vote.

In August, 1920, 35 states had ratified the amendment; 36 states were needed for it to pass. Tennessee was the only state still in the game. Proponents and opponents of the amendment gathered in a Nashville hotel to lobby legislators. The press dubbed it the War of the Roses because supporters of the suffrage movement wore yellow roses in their lapels while its opponents wore red roses.

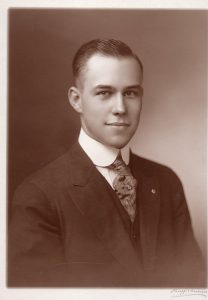

On August 19, the vote appeared to be tied, assuming the count of red and yellow roses was correct. When the roll call came, 24-year-old Harry T. Burn stepped into history. Burn came from a very conservative district and wore a red rose in his lapel, but when asked whether he would vote to ratify the amendment he answered "aye". What changed his mind? A letter from his mother, Febb Burn, who told him to "be a good boy" and vote in favor of the amendment.

- Harry T. Burn

- Febb Burn

Asked later about his change of heart, Burn said “I knew that a mother’s advice is always safest for a boy to follow and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification. I appreciated the fact that an opportunity such as seldom comes to a mortal man to free 17 million women from political slavery was mine.”

If you have the right to vote, use it. Because one vote can in fact change the world.